a feast of fools, for 15 players (2014)

Duration: 17 minutes

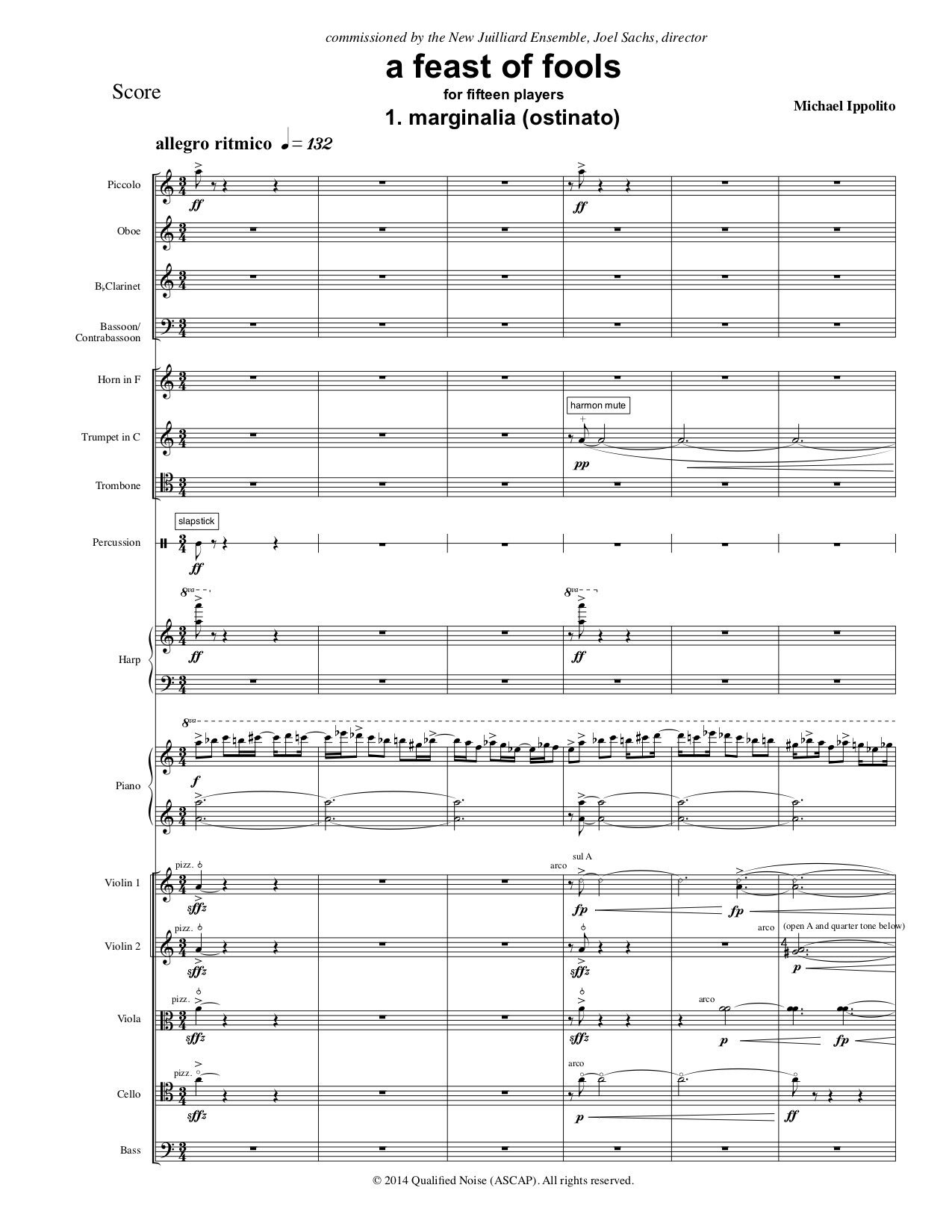

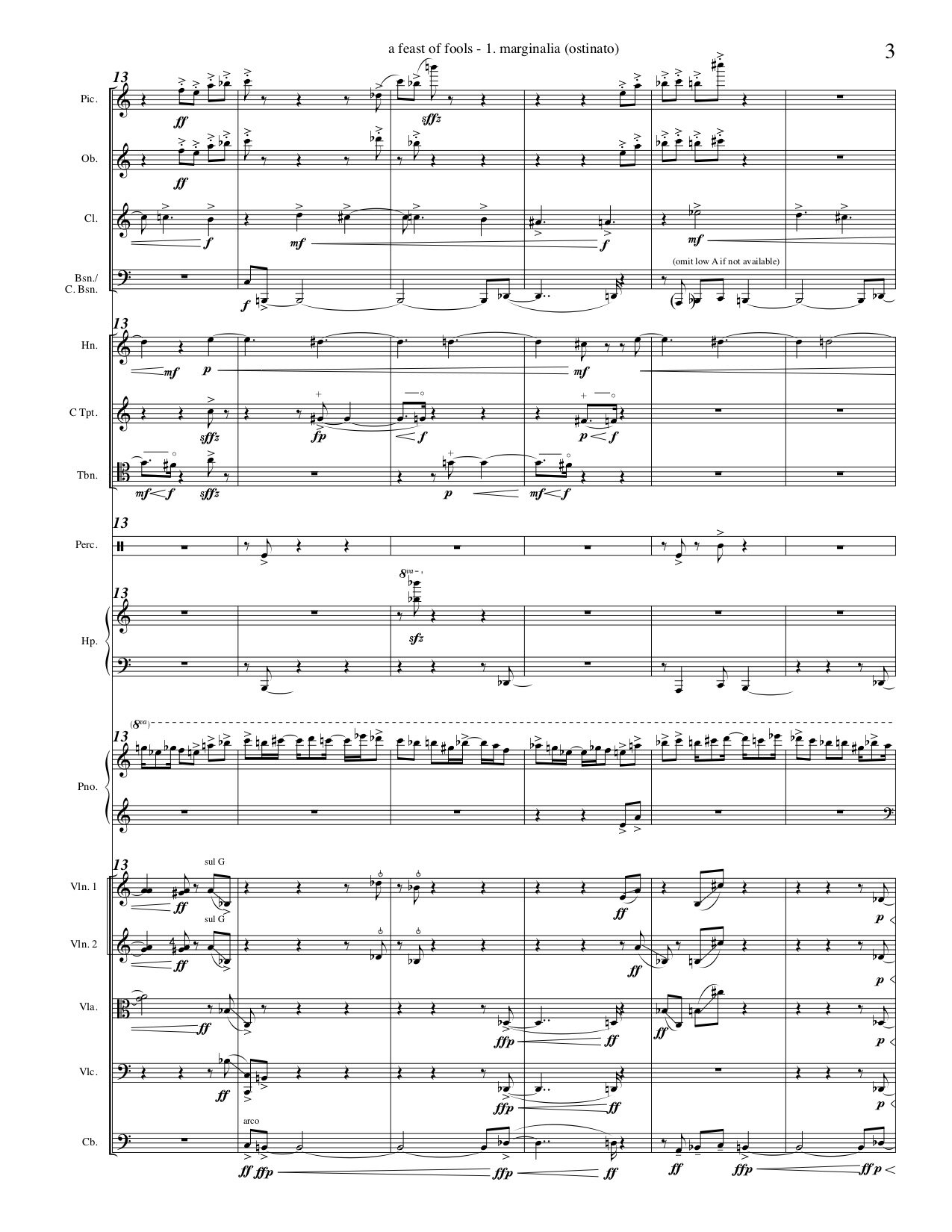

Instrumentation: flute (piccolo), oboe, clarinet (bass clarinet), bassoon (contrabassoon), horn, trumpet, trombone, percussion, harp, piano, 2 violins, viola, cello, bass

Premiere: April 1, 2014 by The New Juilliard Ensemble, conducted by Joel Sachs at Alice Tully Hall

Notes:

The medieval feast of fools was a time of drunkenness and bawdy humor, of social inversion, ceremonial parody and licensed foolishness. I have always loved this image, partially because it defies our conventional impression of the Middle Ages as a bleak and humorless era. But mostly because it reminds me that people are essentially the same throughout history, not so much because we share lofty goals and higher purpose, but because we have been making the same stupid jokes and acting like fools for centuries. It is with this in mind that I wrote a feast of fools, a set of three movements each inspired by medieval artifacts of foolishness.

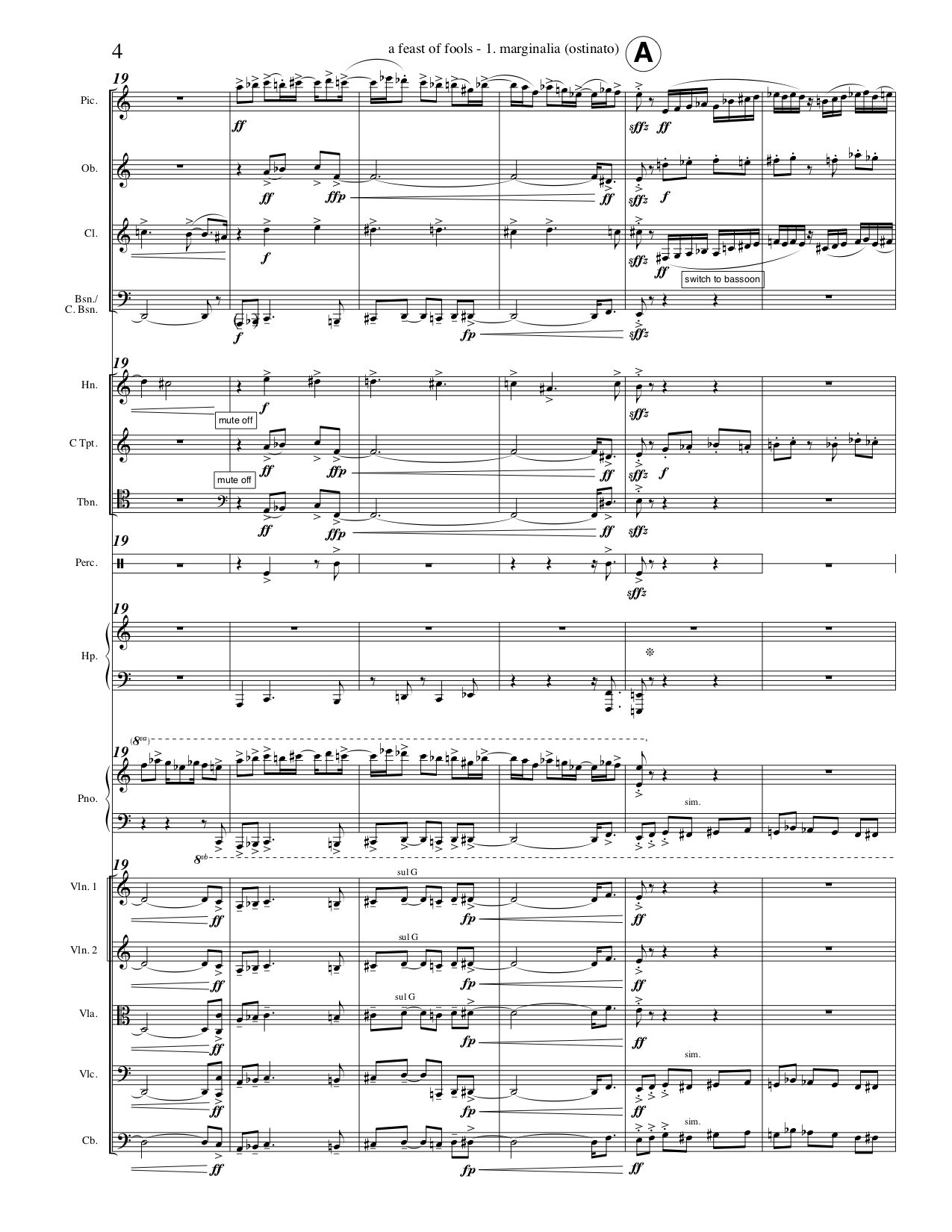

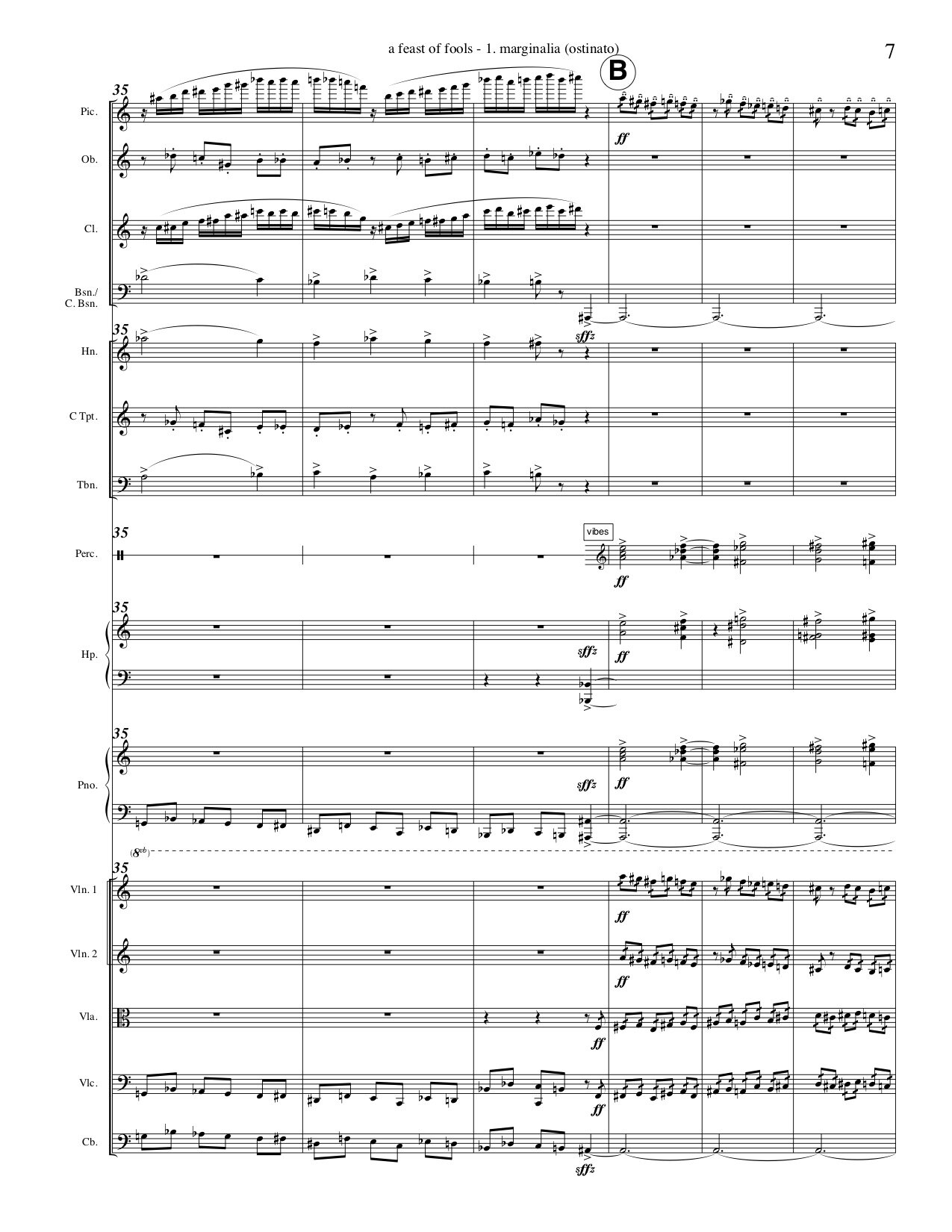

The first movement, marginalia, was suggested by the strange and often funny drawings sketched by monks in the margins of manuscripts. To me, these grotesque creatures and irreverent caricatures breathe life into the long-forgotten people who drew them. Through these images, one can imagine the boredom of a life spent in isolation in a library, copying manuscripts day after day. The repetitive task suggested a restless ostinato that yields various deformations and elaborations as the piece progresses.

The second movement, serenade, is based on a medieval song by Gilles Binchois called Triste plaisir. The original text of the song is a series of oxymorons (sad pleasure, sorrowful joy, bitter sweetness, etc) resulting in a mix of playfulness and melancholy that is a kind of elevated foolishness, an example of art as play. In my piece, the harp plays in the style of a lute or guitar transcription of the original song, alternating with music played by the full ensemble.

The final movement, introduction and nasentanz, celebrates the carnivalesque and ribald humor of medieval drinking songs. Most of the music was derived from the song Vitrum nostrum gloriosum (Our glorious glass), a parody of church music that replaces devotional text with an ode to wine. In addition, the idea of the nasentanz (nose-dance) comes from a German woodcut and accompanying poem describing a town of fools, drunk and dancing, who hold a contest for the largest nose (with prizes including a “nose sock” among other bizarre details). My third movement begins with an evocation of church music and an approaching processional, introducing the earthy nasentanz, which I imagine accompanying the increasingly drunk dancers.