Machine Become Music, for large wind ensemble (2017)

Duration: 27 minutes

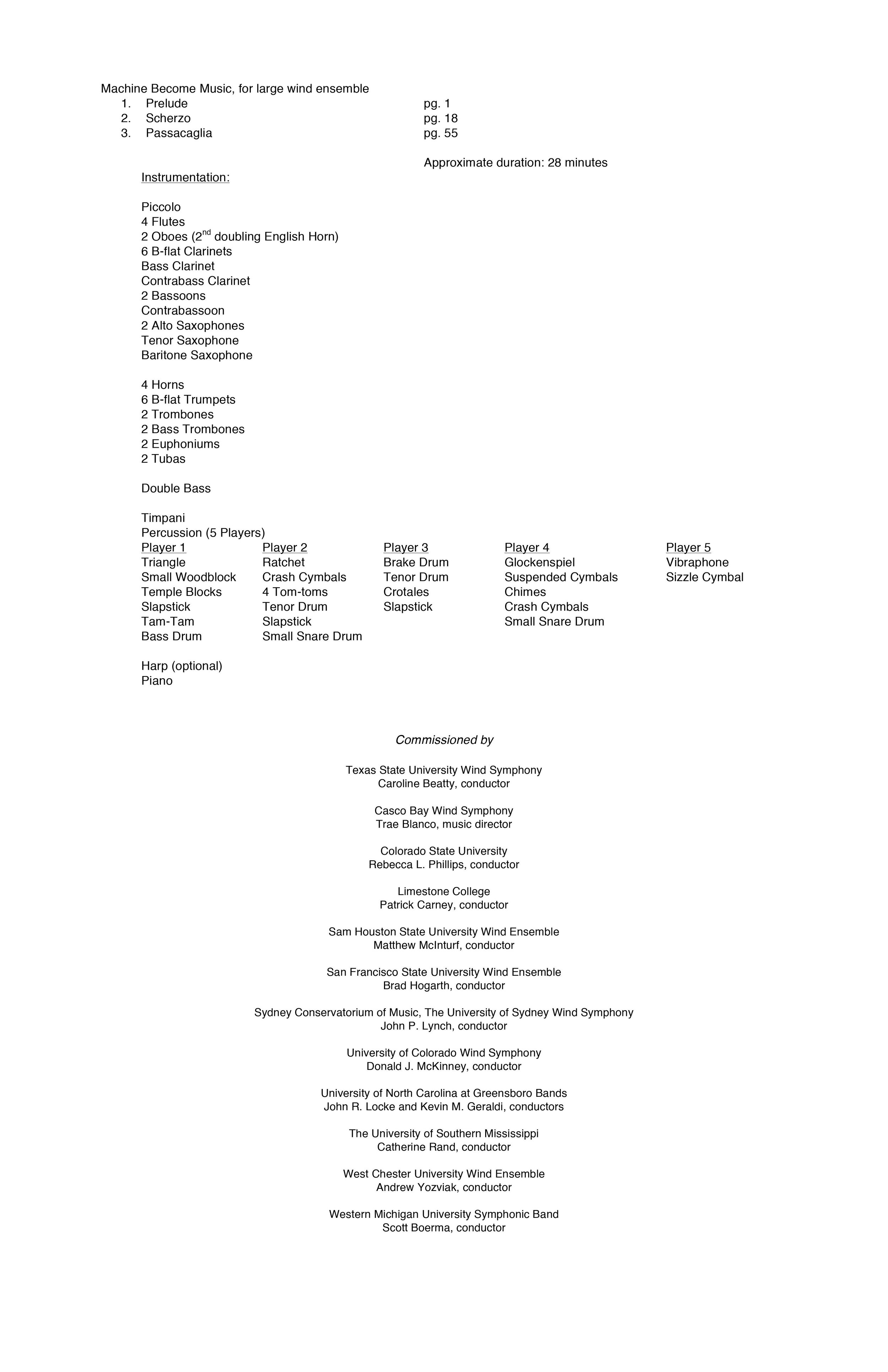

Instrumentation: piccolo, 4 flutes, 2 oboes, english horn, e-flat clarinet, 6 b-flat clarinets, bass clarinet, b-flat contrabass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 2 alto saxes, tenor sax, baritone sax, 4 horns, 6 b-flat trumpets, 2 trombones, 2 bass trombones, 2 euphoniums, 2 tubas, double bass, timpani, 5 percussionists, harp, piano

Click here for perusal score/rental info

Premiere: October 6, 2017 at Evans Auditorium San Marcos, TX by the Texas State University Wind Symphony, Caroline Beatty, conductor

Notes:

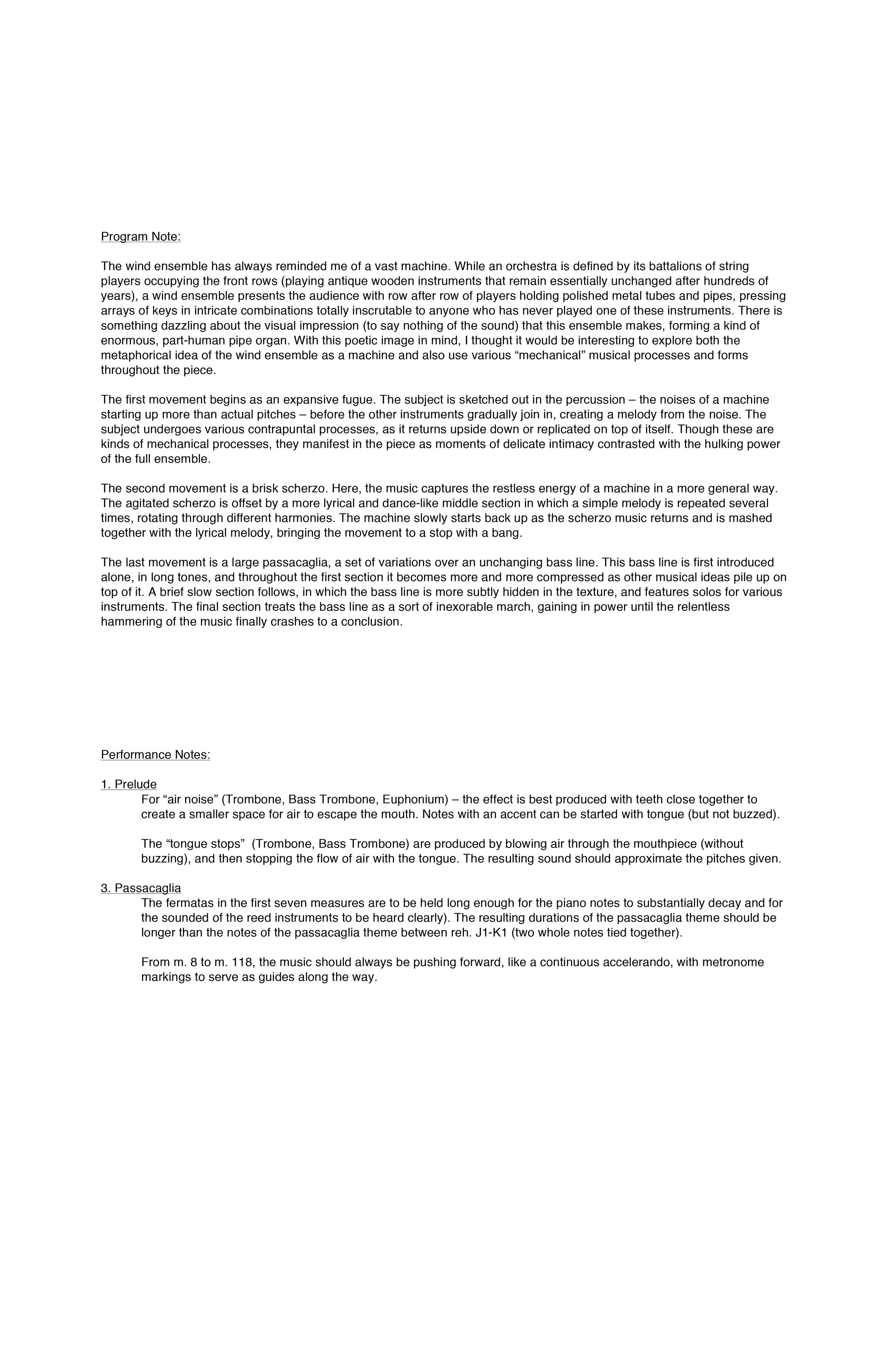

The wind ensemble has always reminded me a vast machine. While an orchestra is defined by its battalions of string players occupying the front rows (playing antique wooden instruments that remain essentially unchanged after hundreds of years), a wind ensemble presents the audience with row after row of players holding polished metal tubes and pipes, pressing arrays of keys in intricate combinations totally inscrutable to anyone who has never played one of these instruments. There is something dazzling about the visual impression (to say nothing of the sound) that this ensemble makes, forming a kind of enormous, part-human pipe organ. With this poetic image in mind, I thought it would be interesting to explore both the metaphorical idea of the wind ensemble as a machine and also use various “mechanical” musical processes and forms throughout the piece.

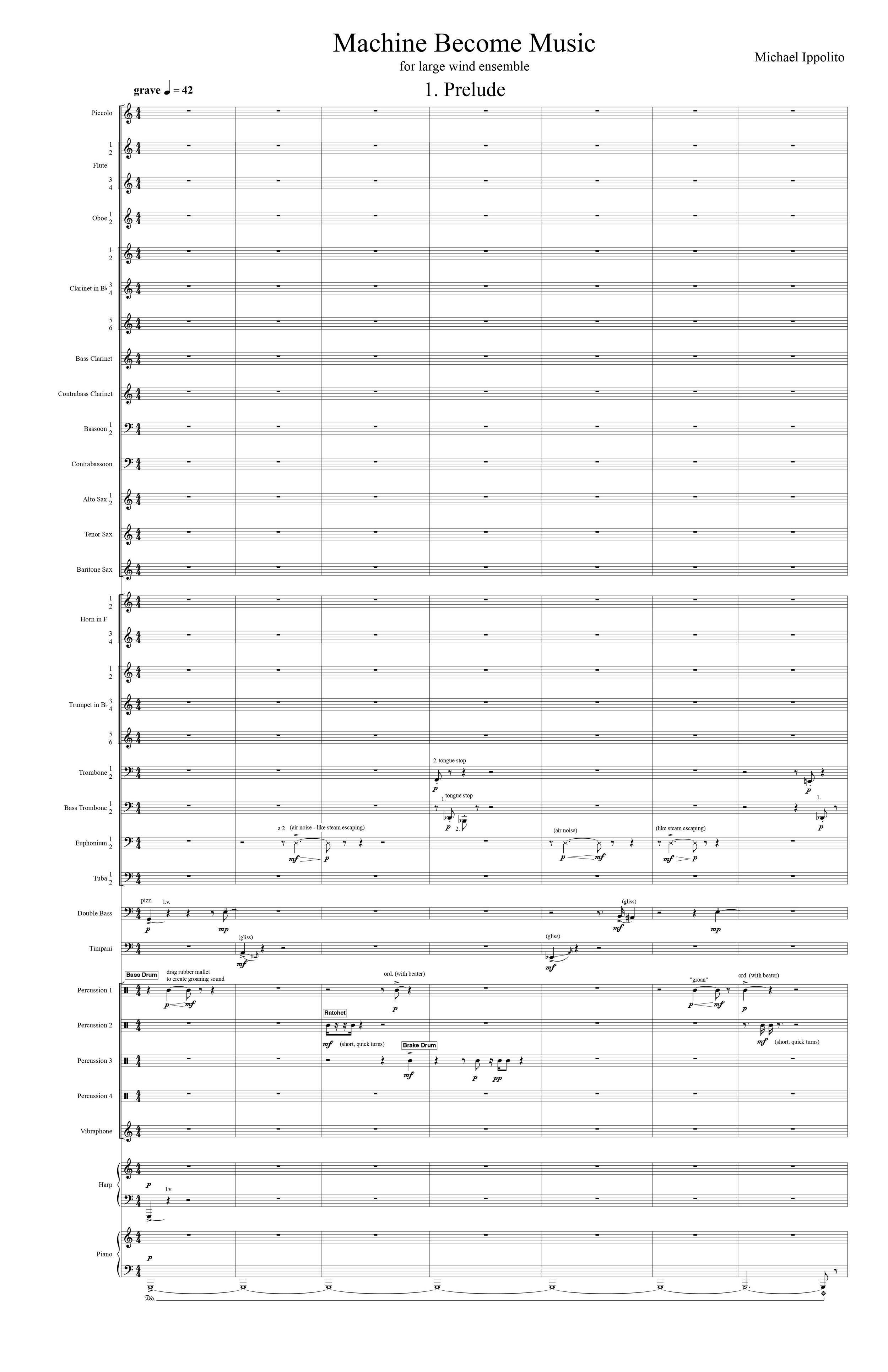

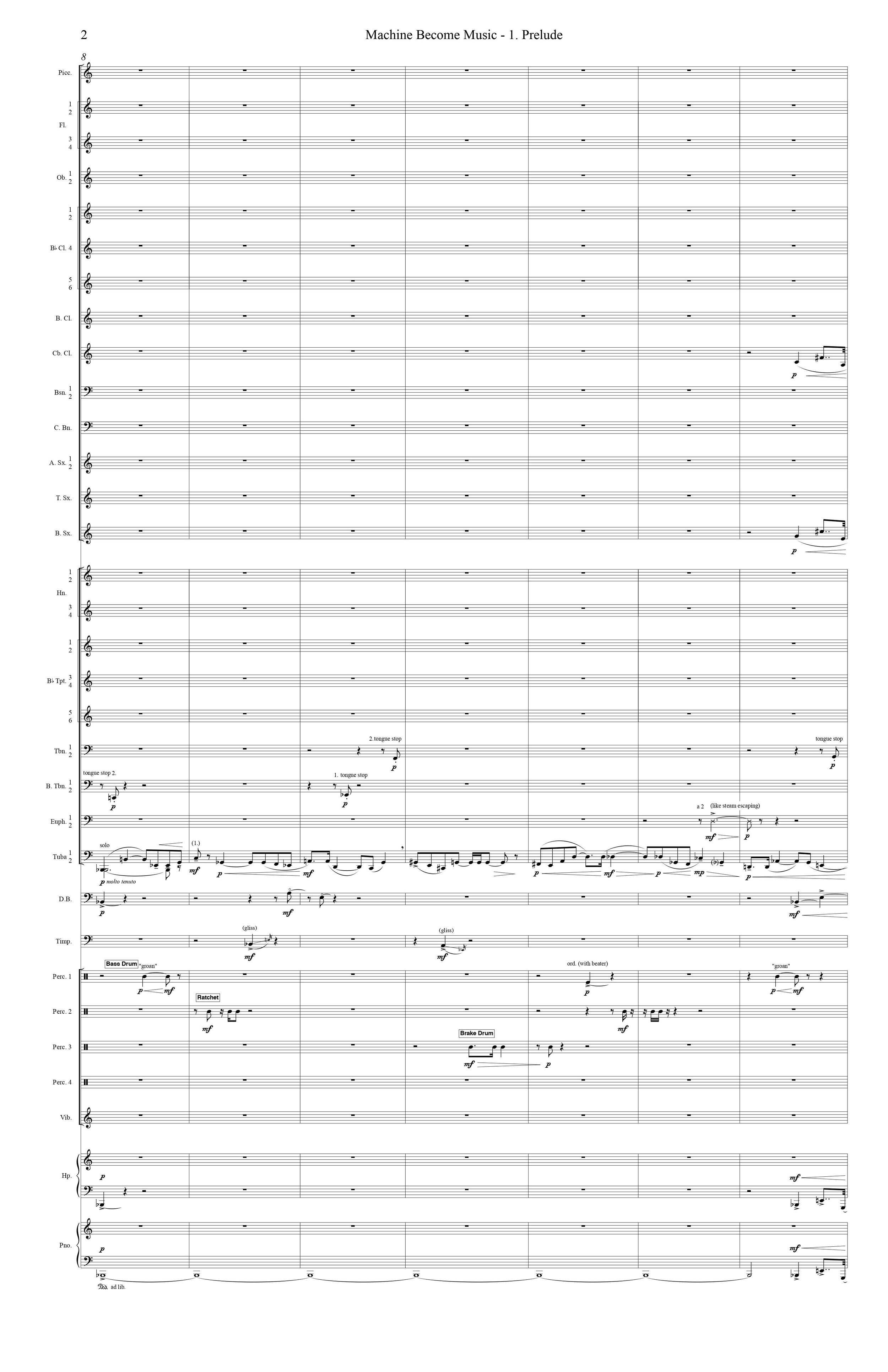

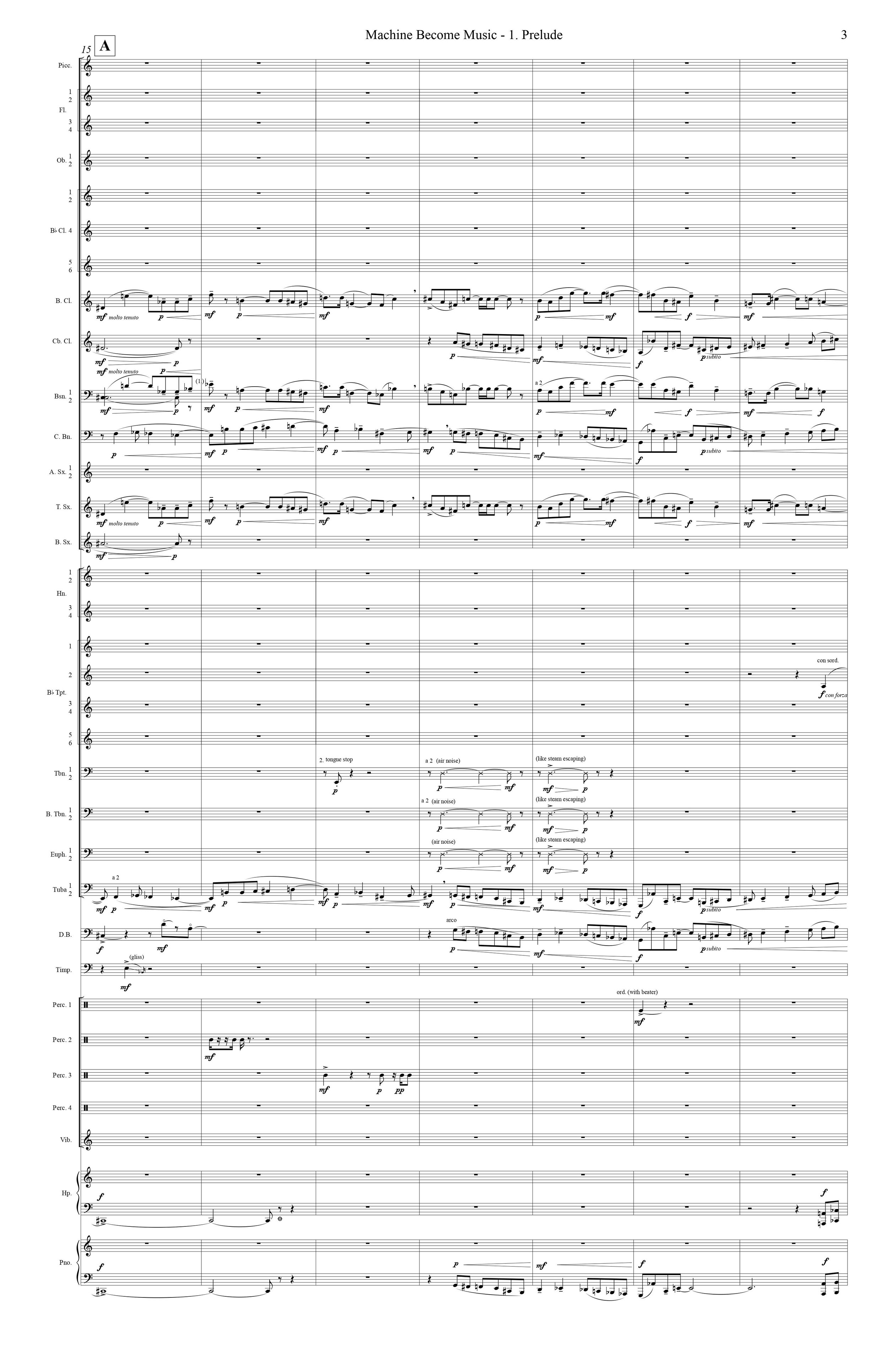

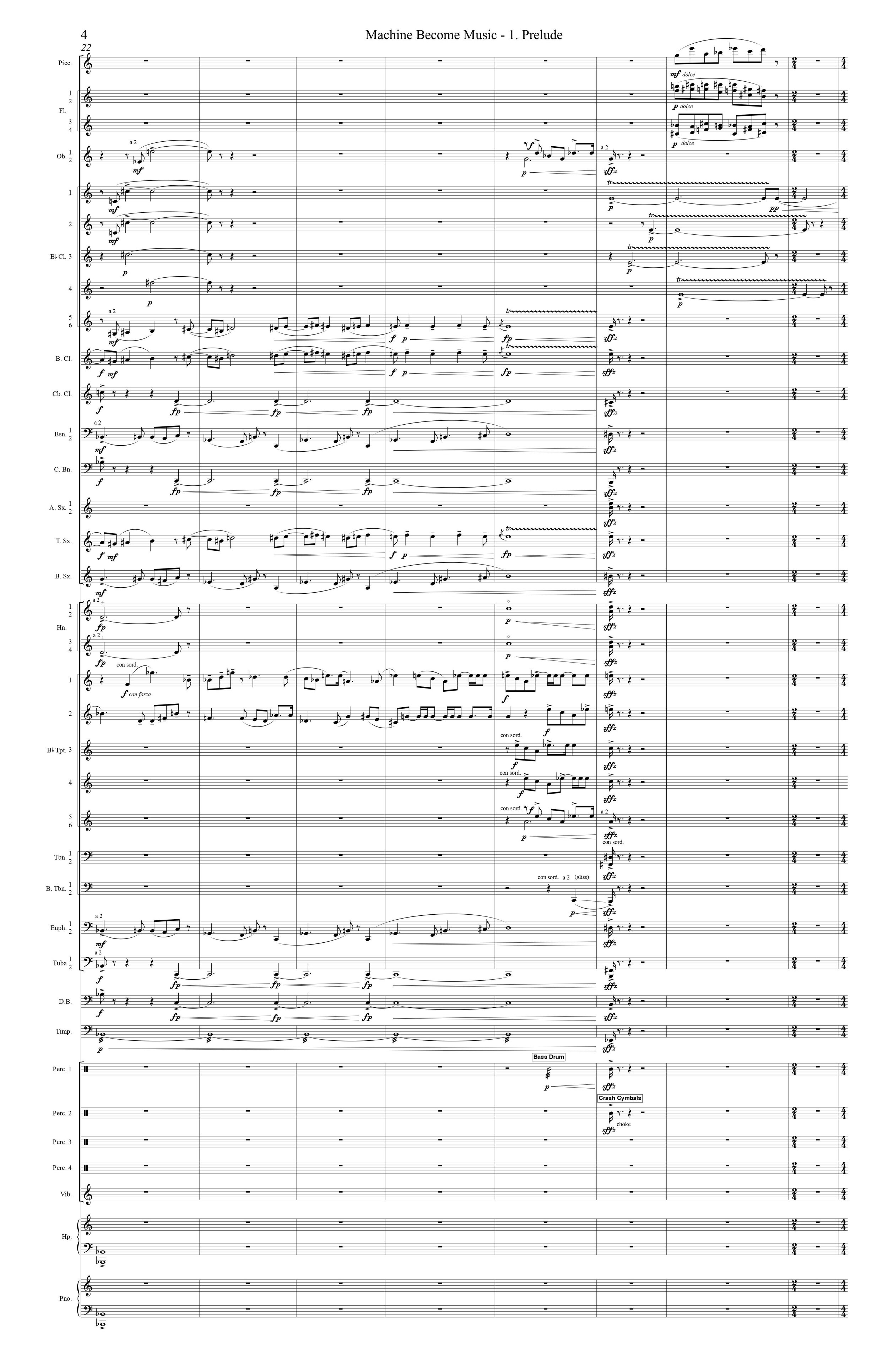

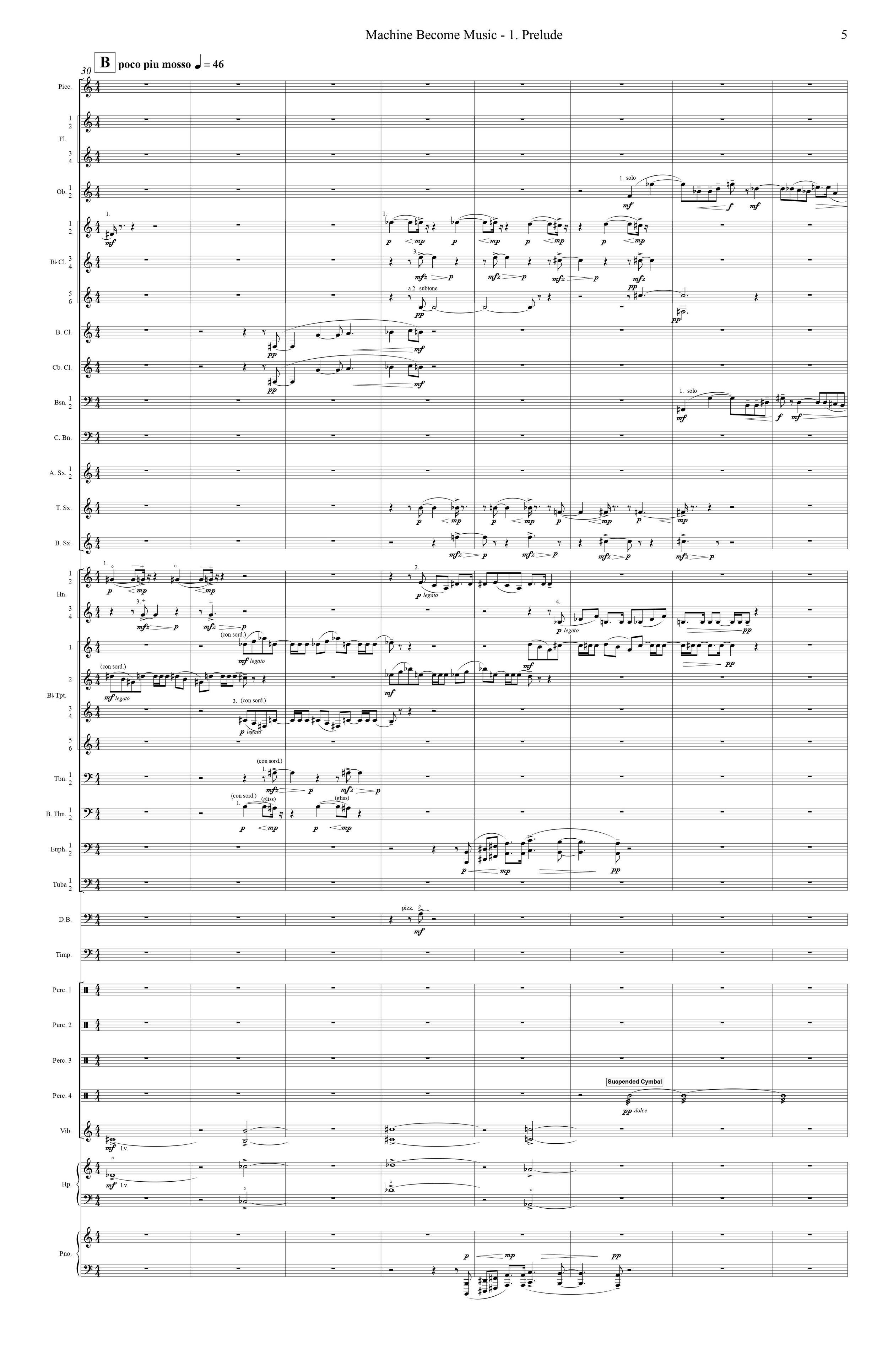

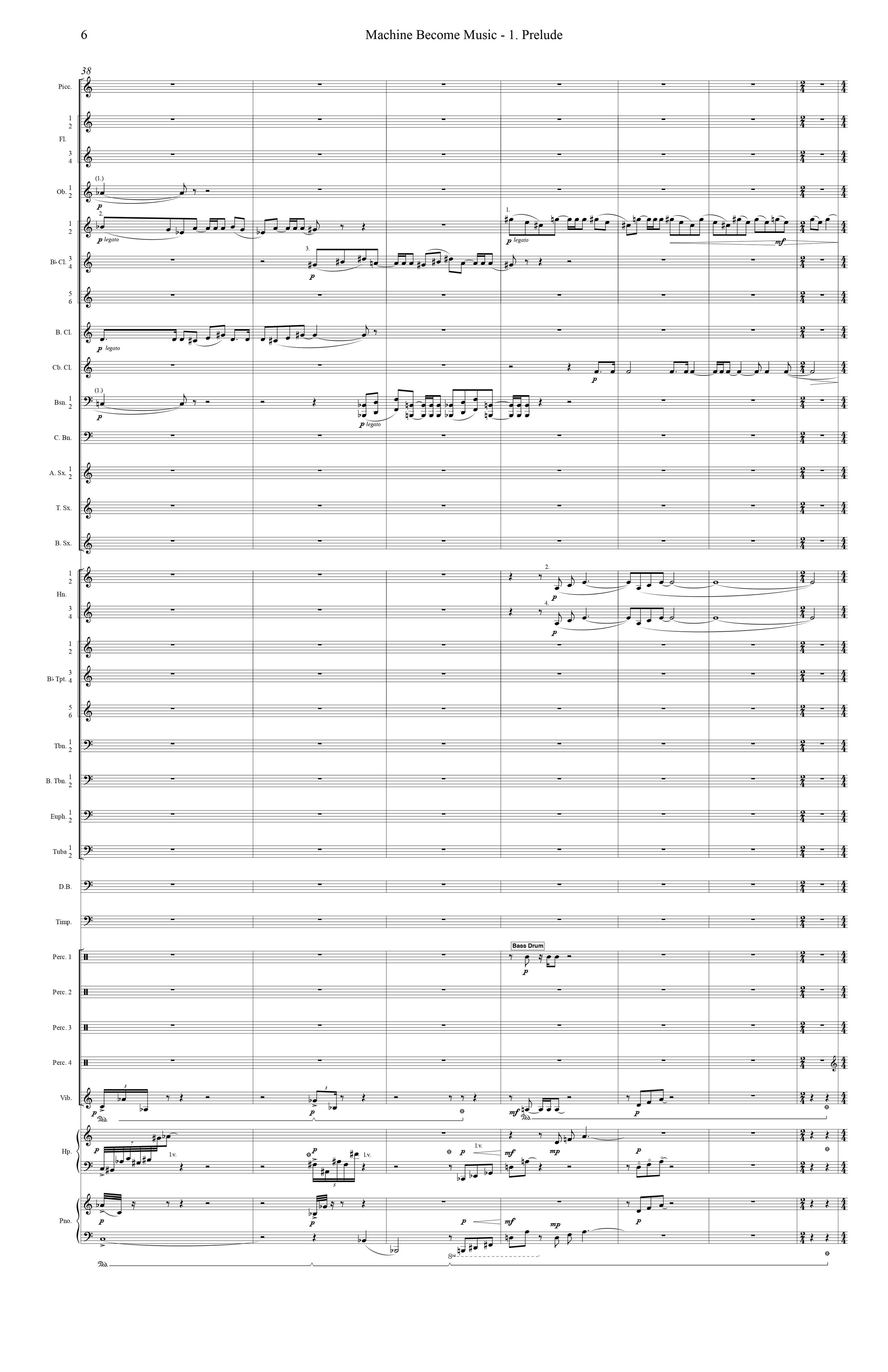

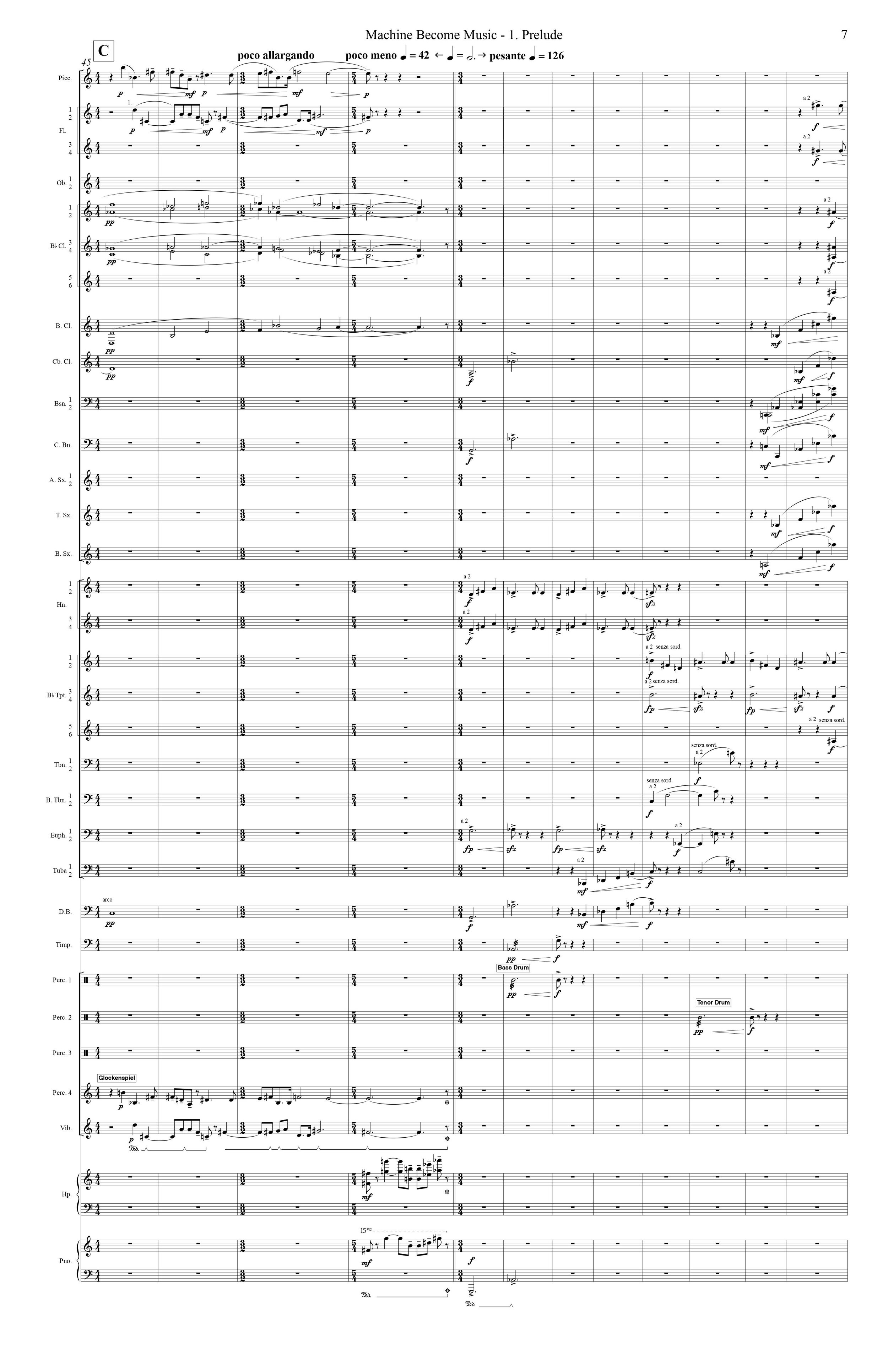

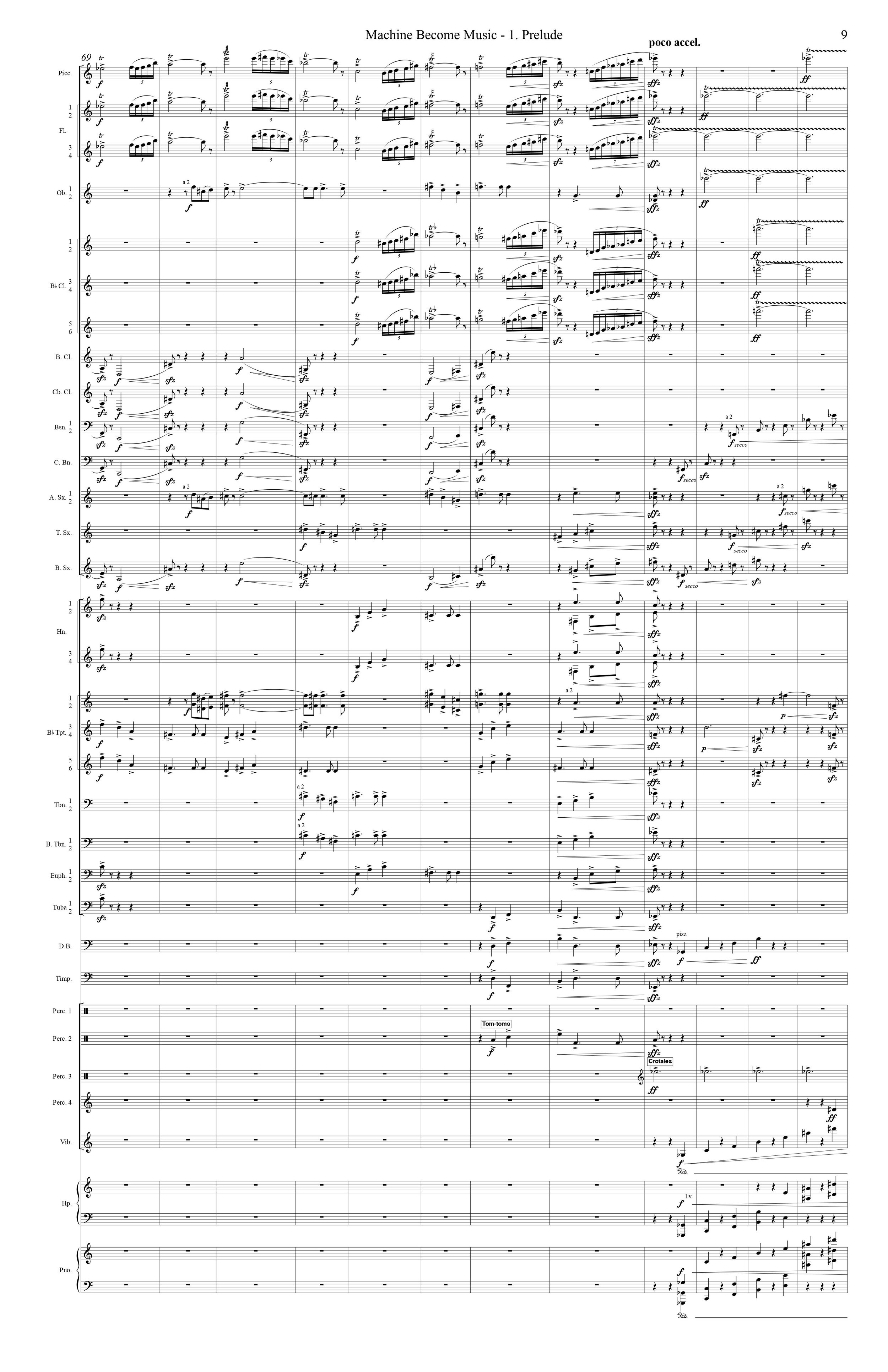

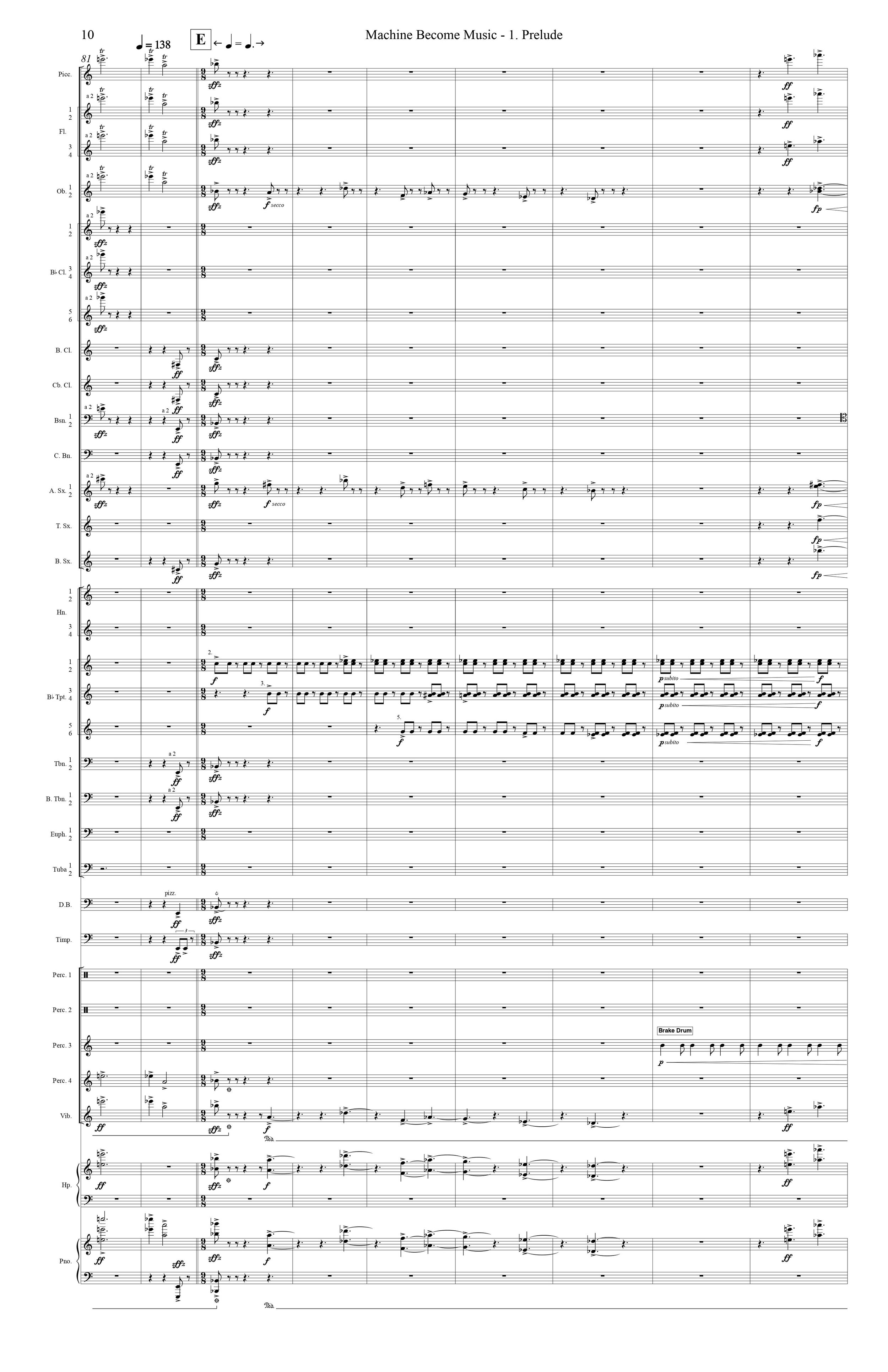

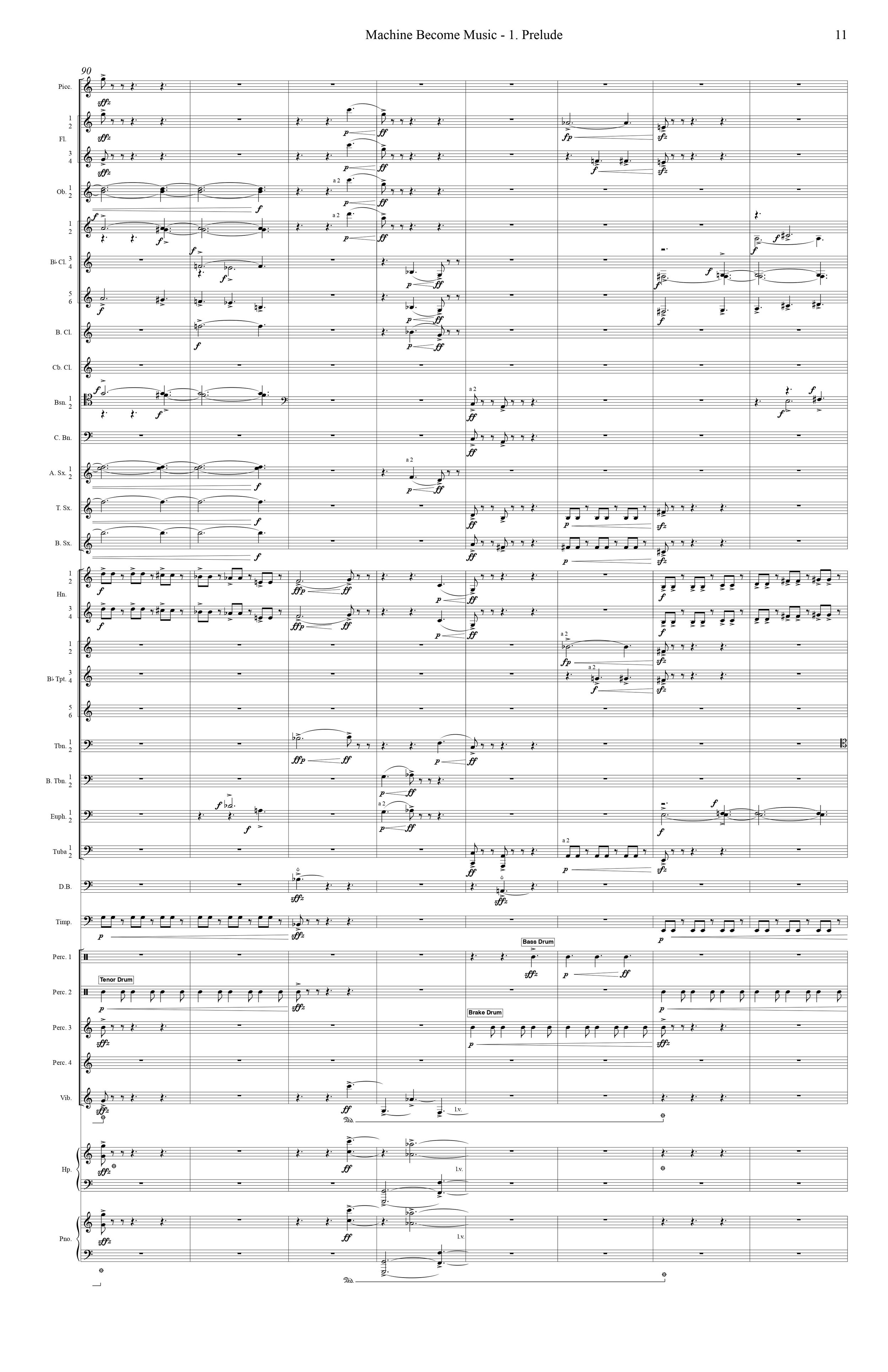

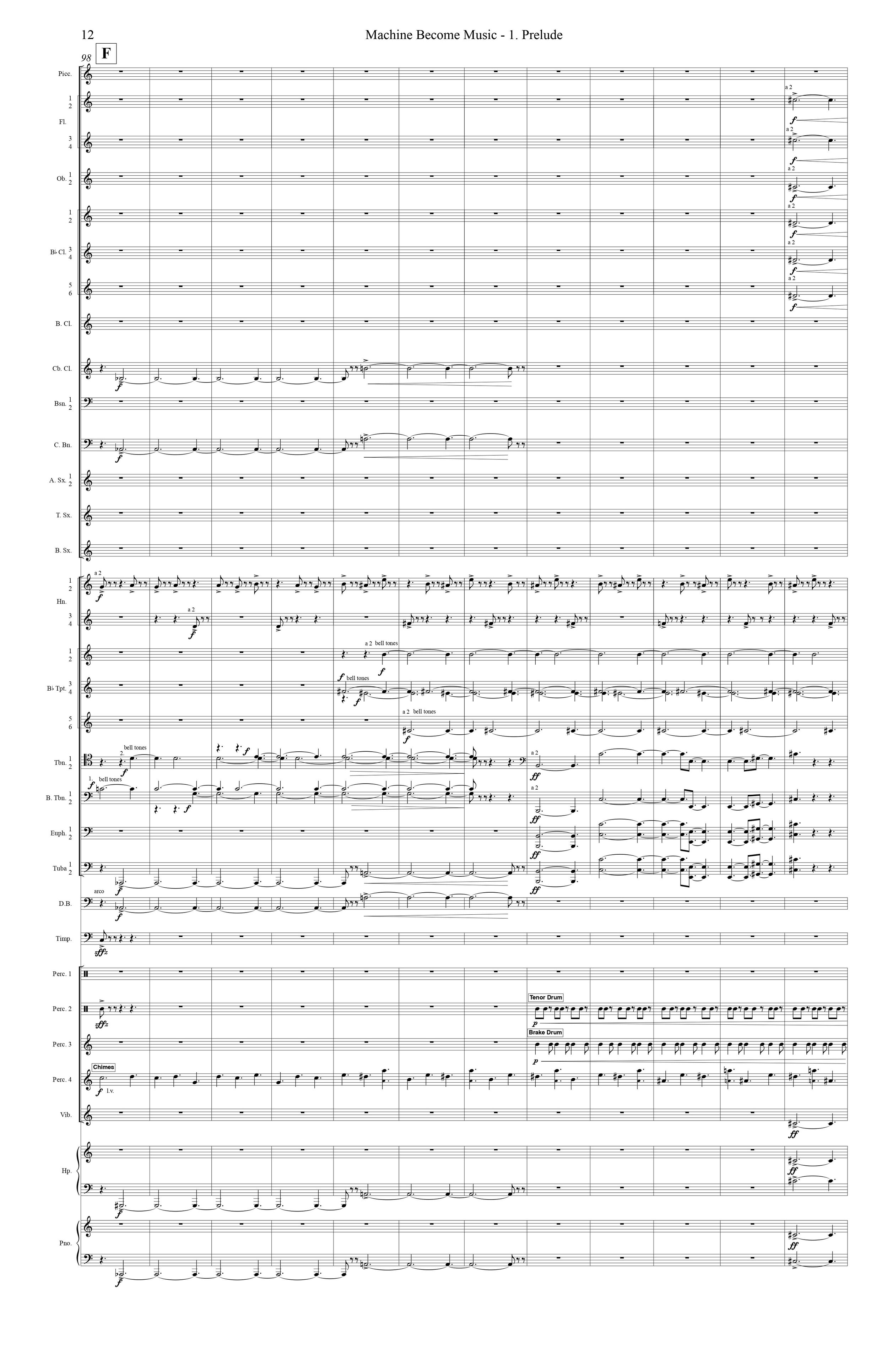

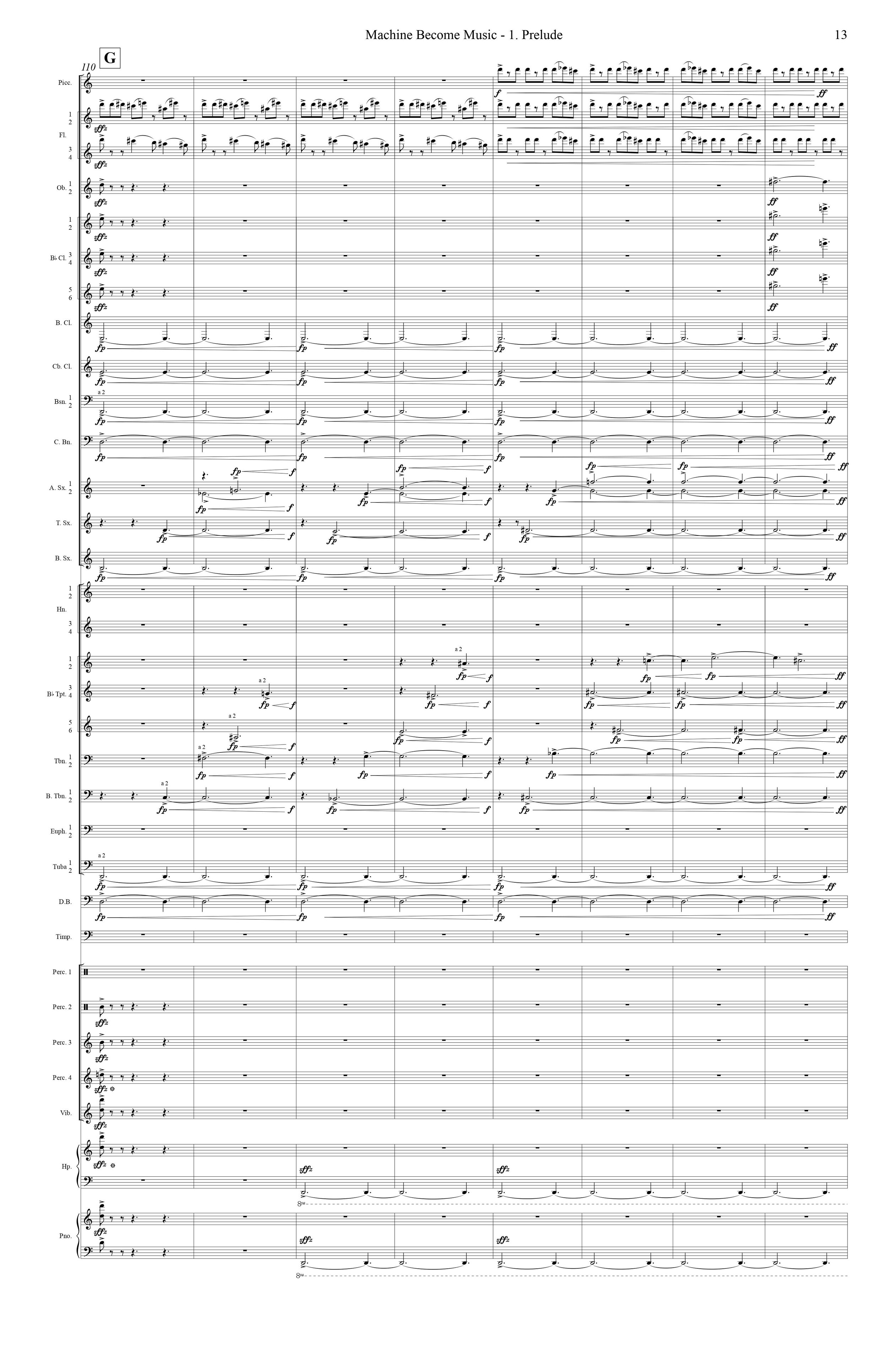

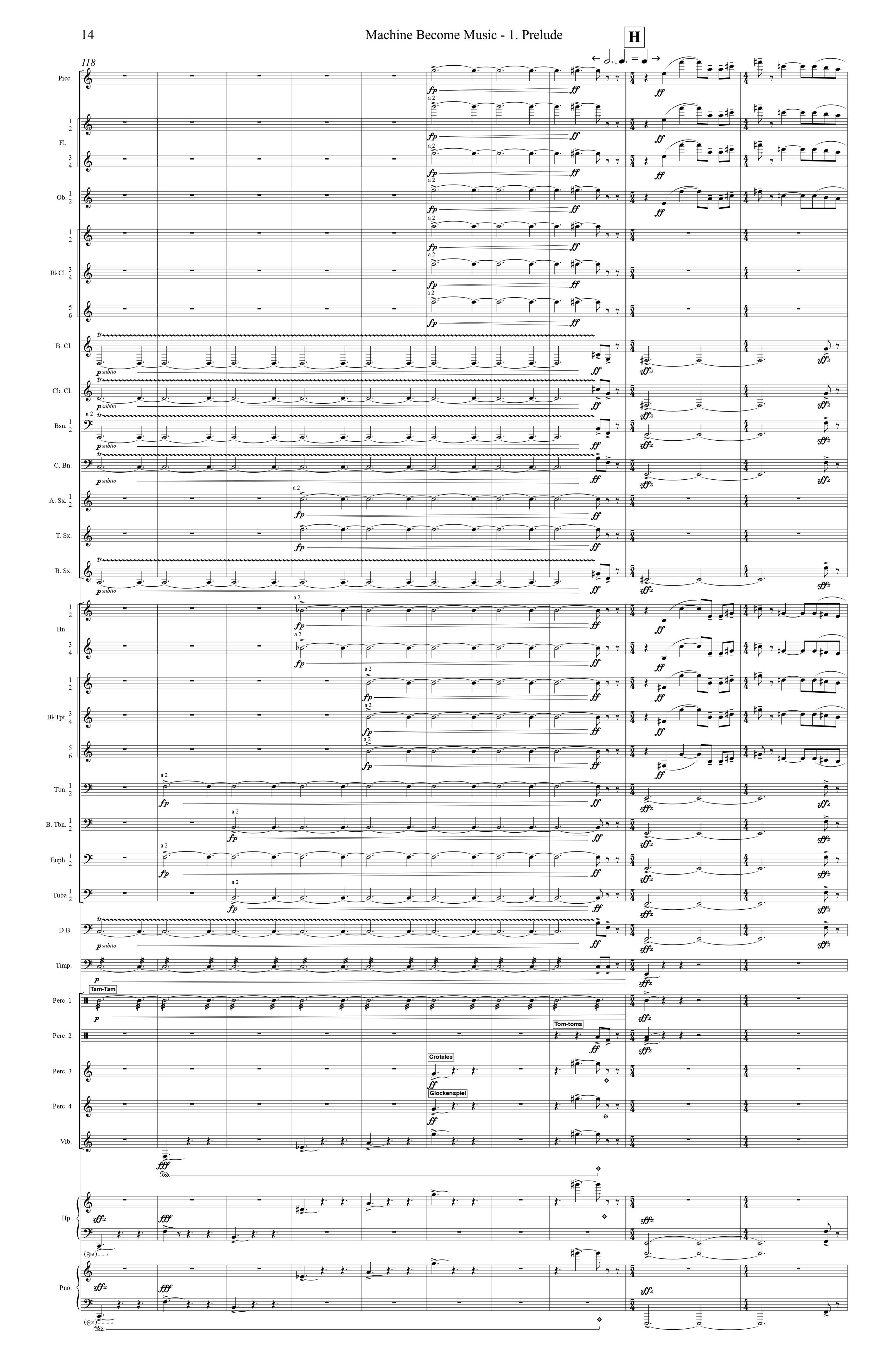

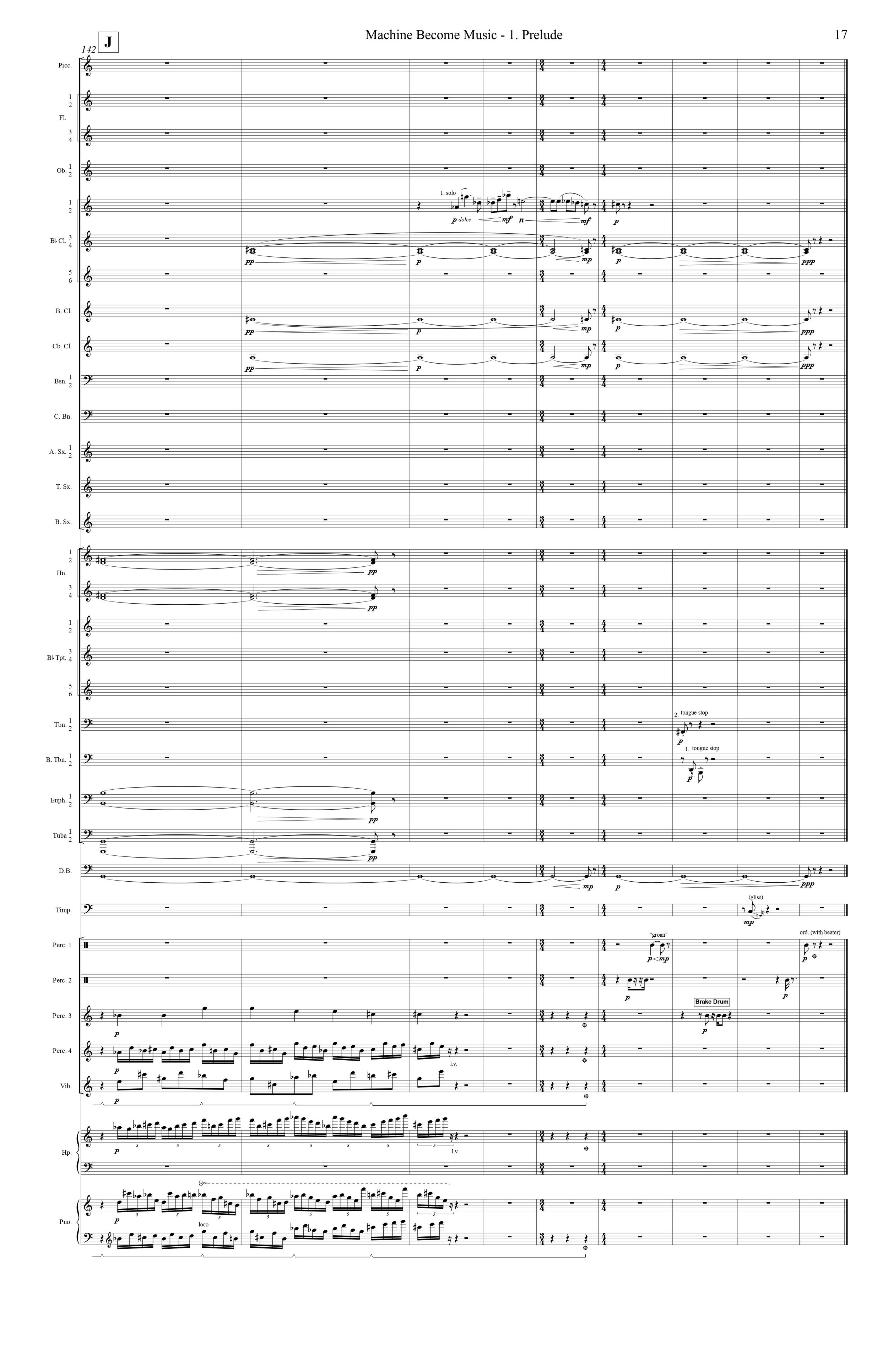

The first movement begins as an expansive fugue. The subject is sketched out in the percussion – the noises of a machine starting up more than actual pitches – before the other instruments gradually join in, creating a melody from the noise. The subject undergoes various contrapuntal processes, as it returns upside down or replicated on top of itself. Though these are kinds of mechanical processes, they manifest in the piece as moments of delicate intimacy contrasted with the hulking power of the full ensemble.

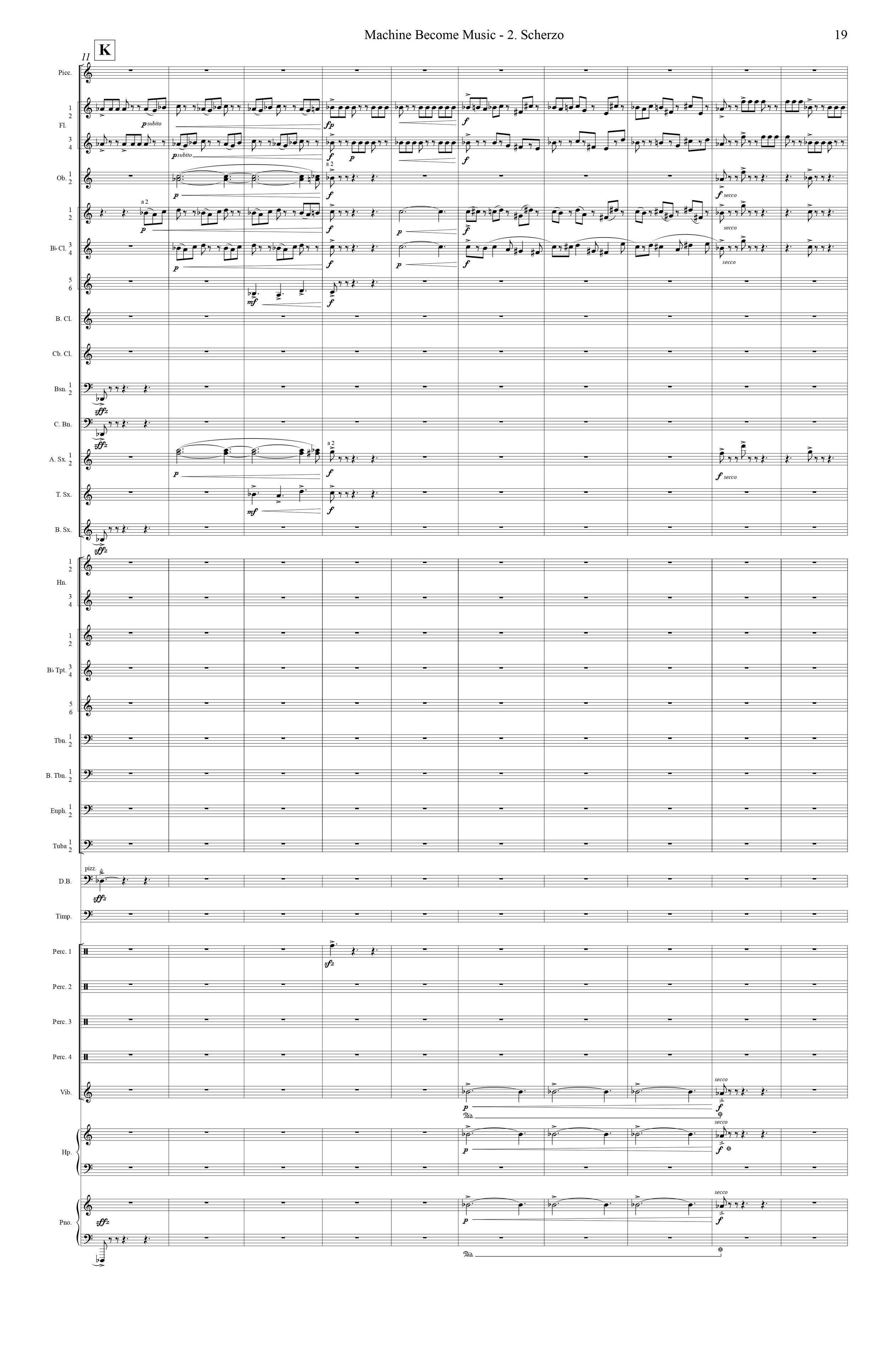

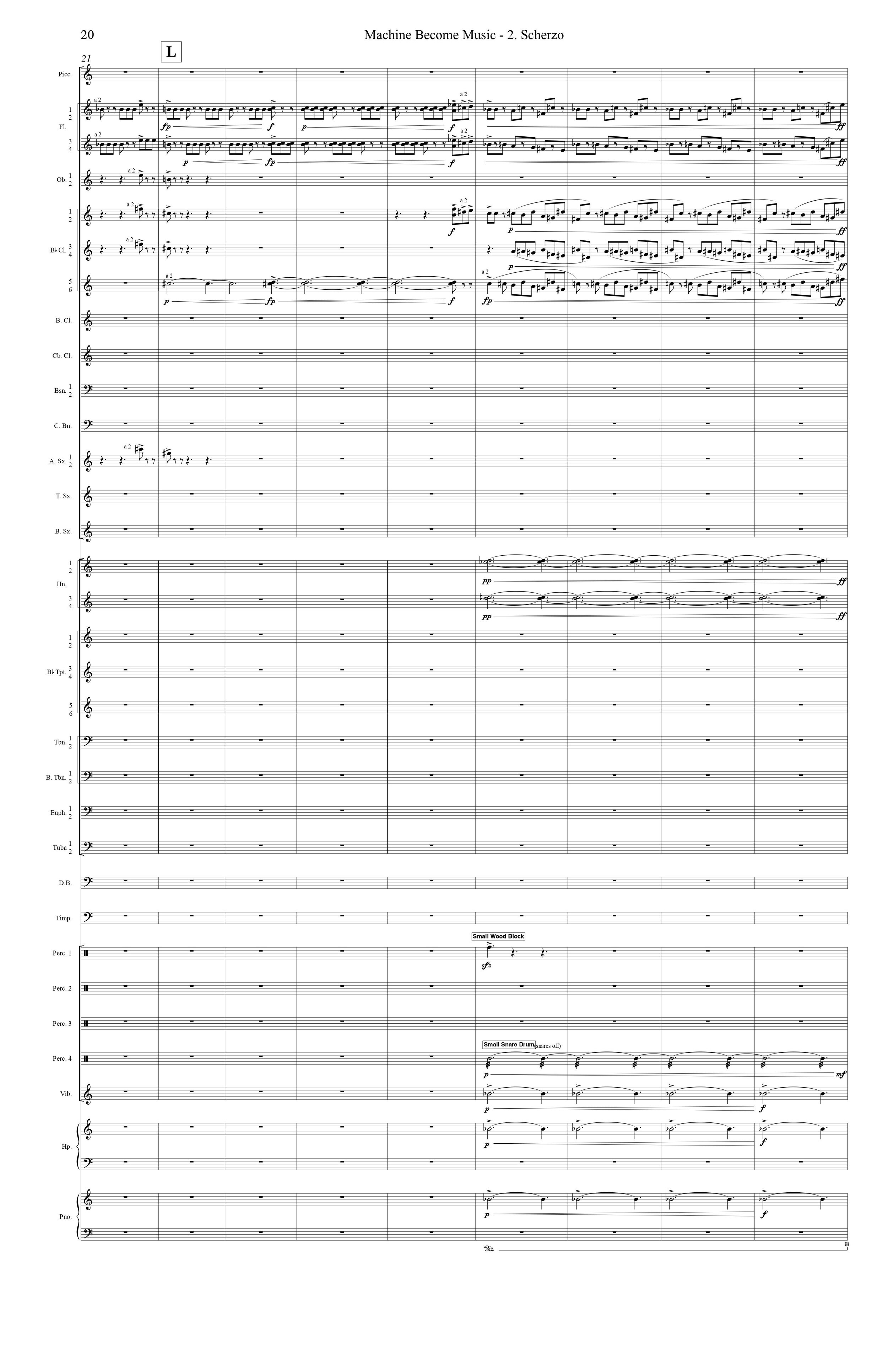

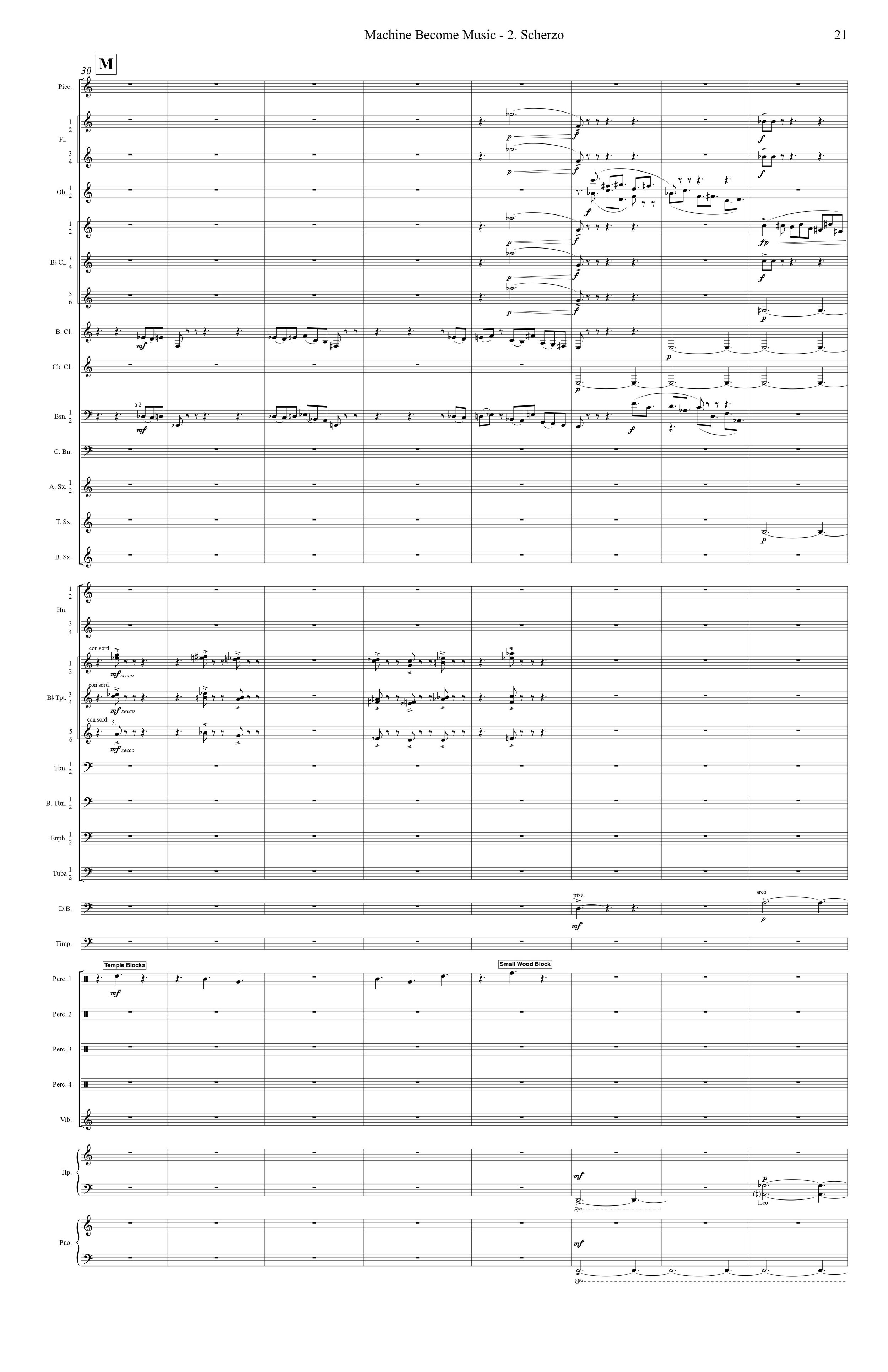

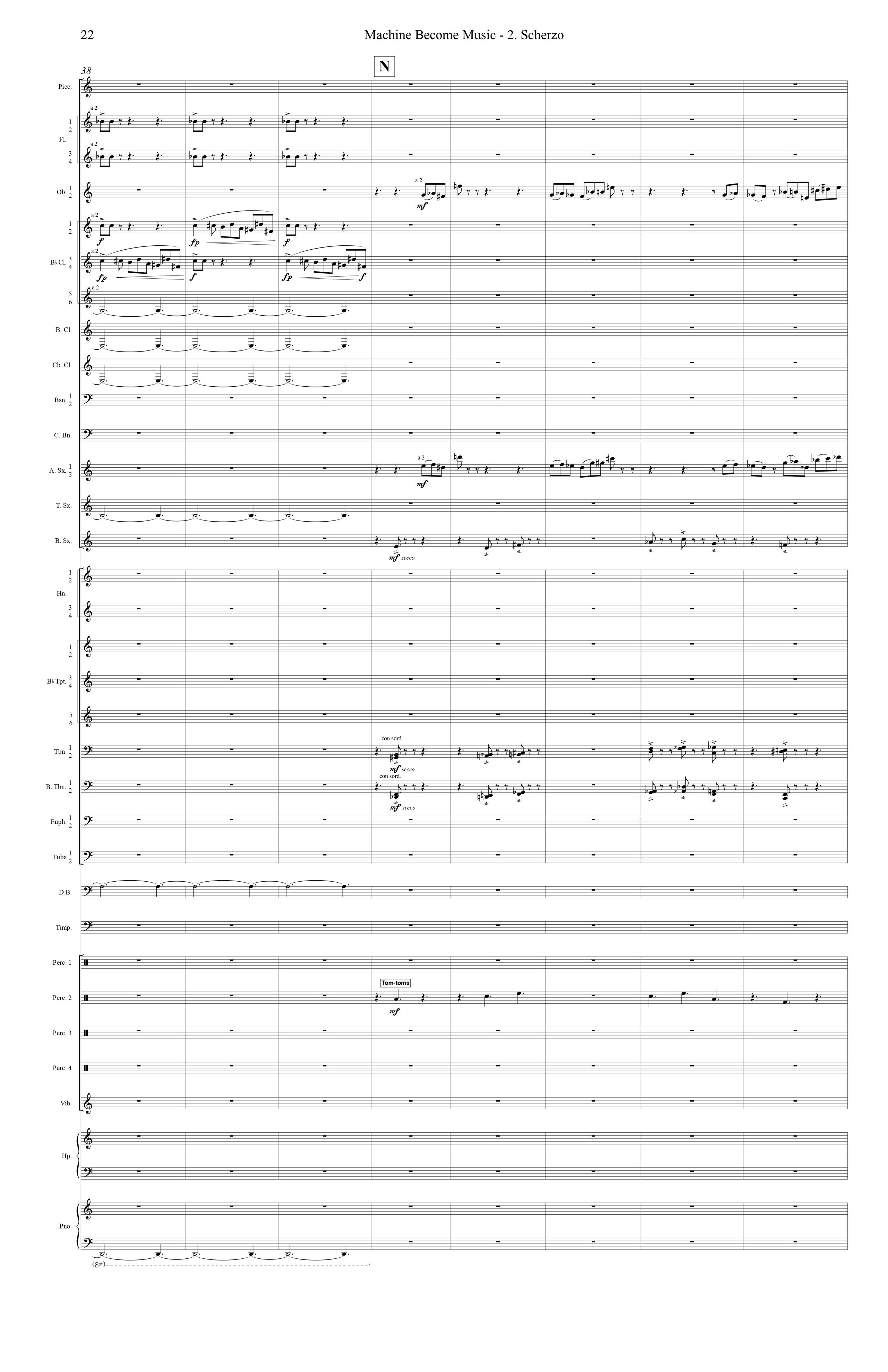

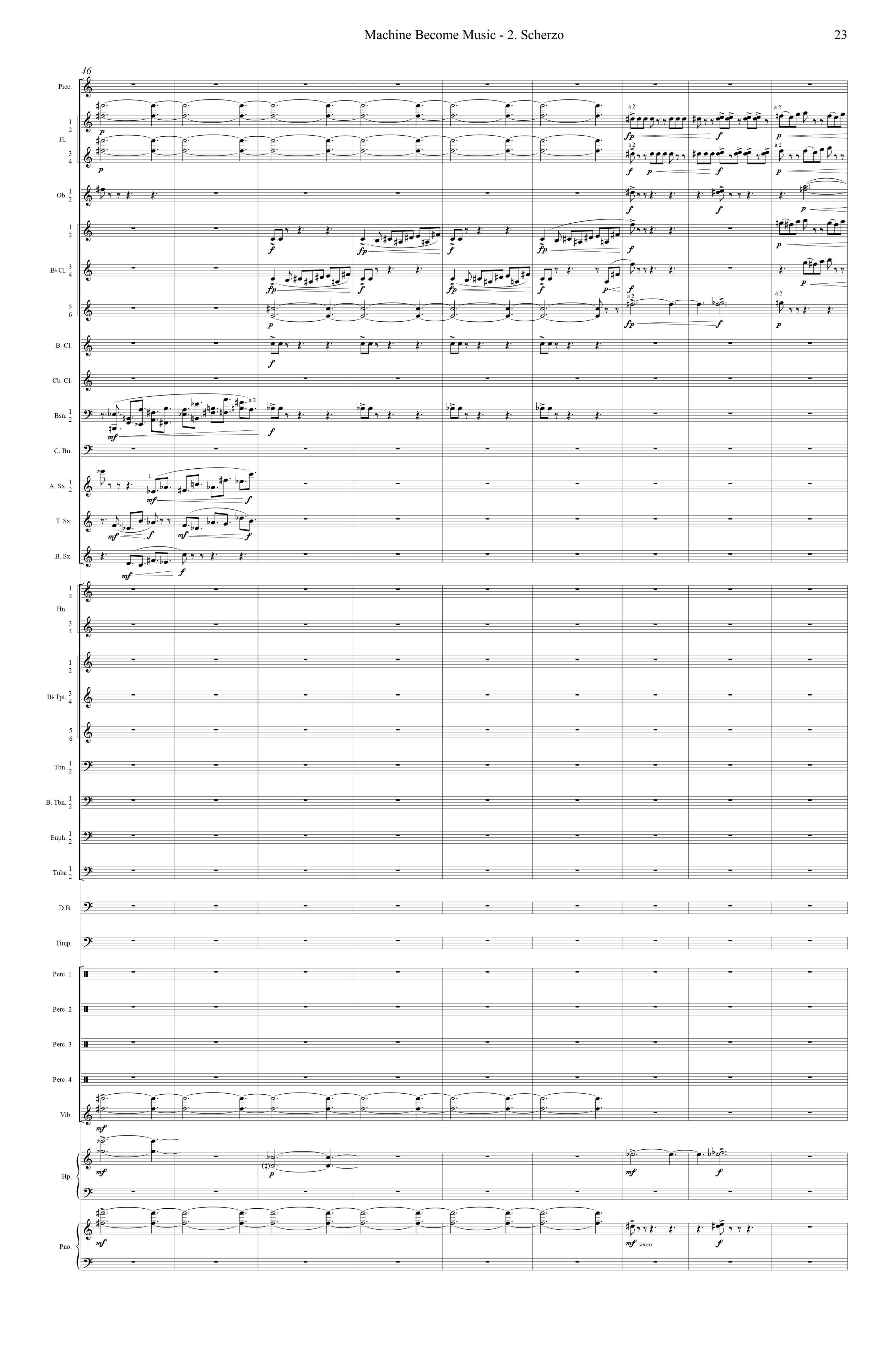

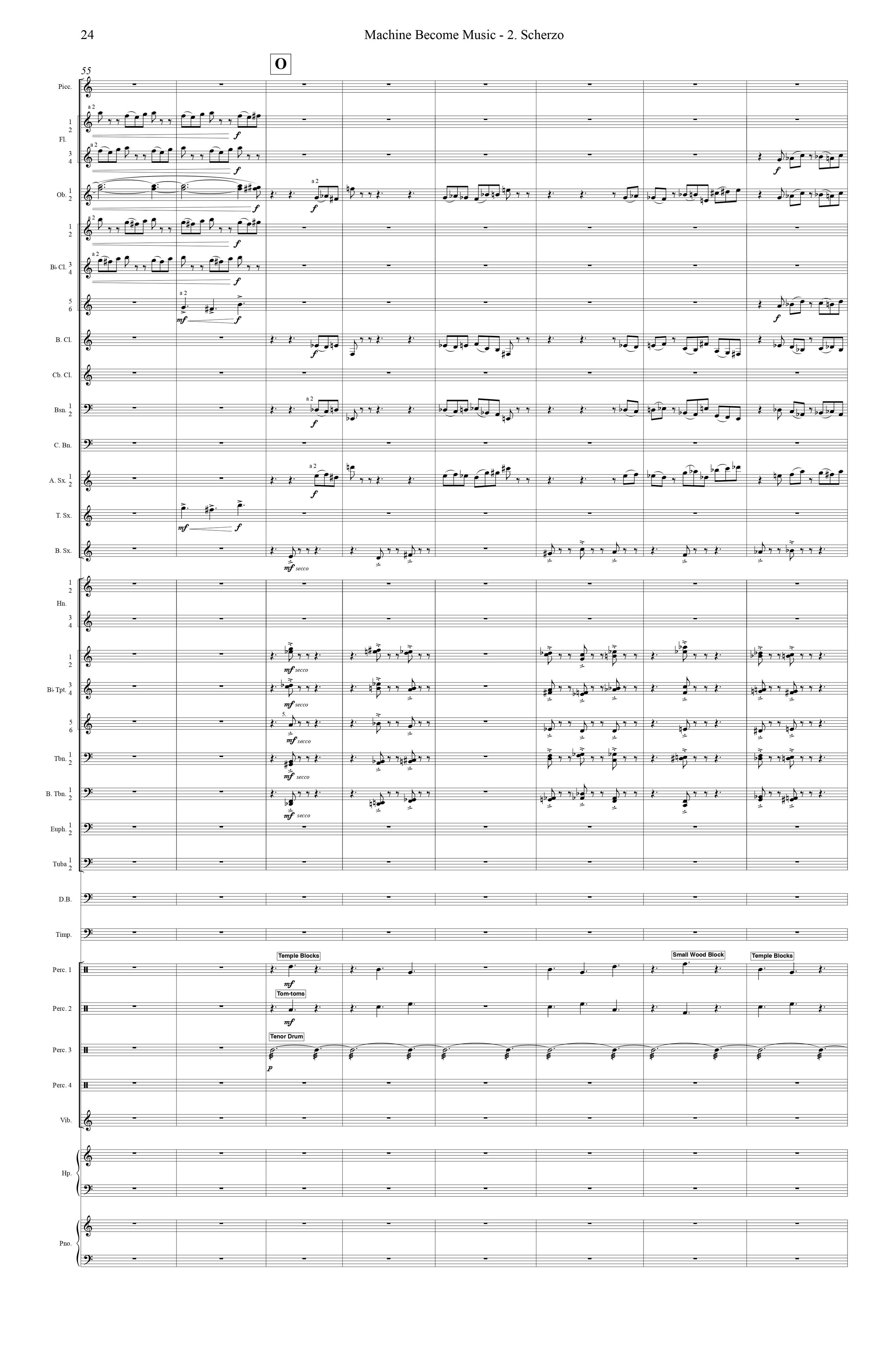

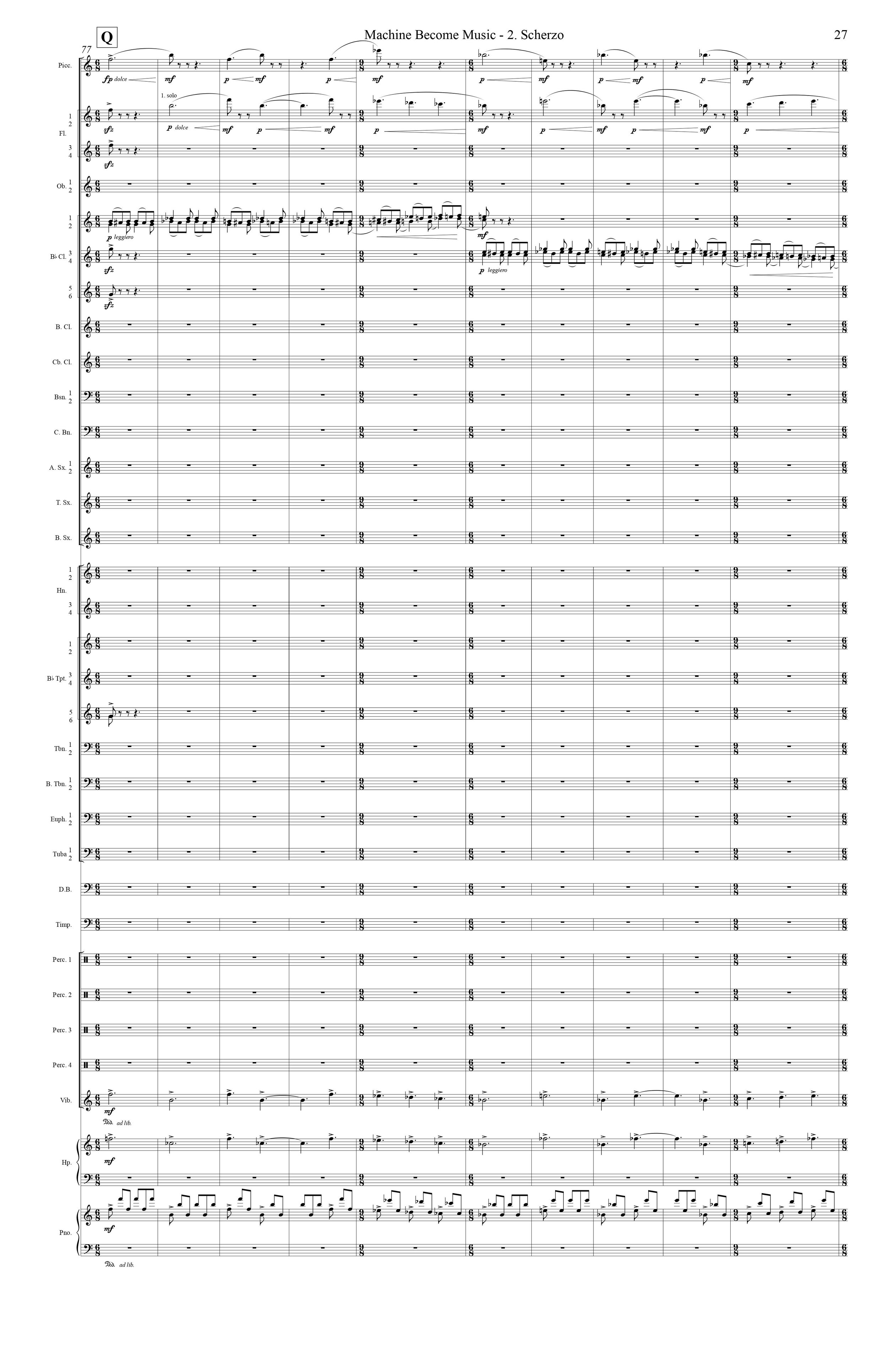

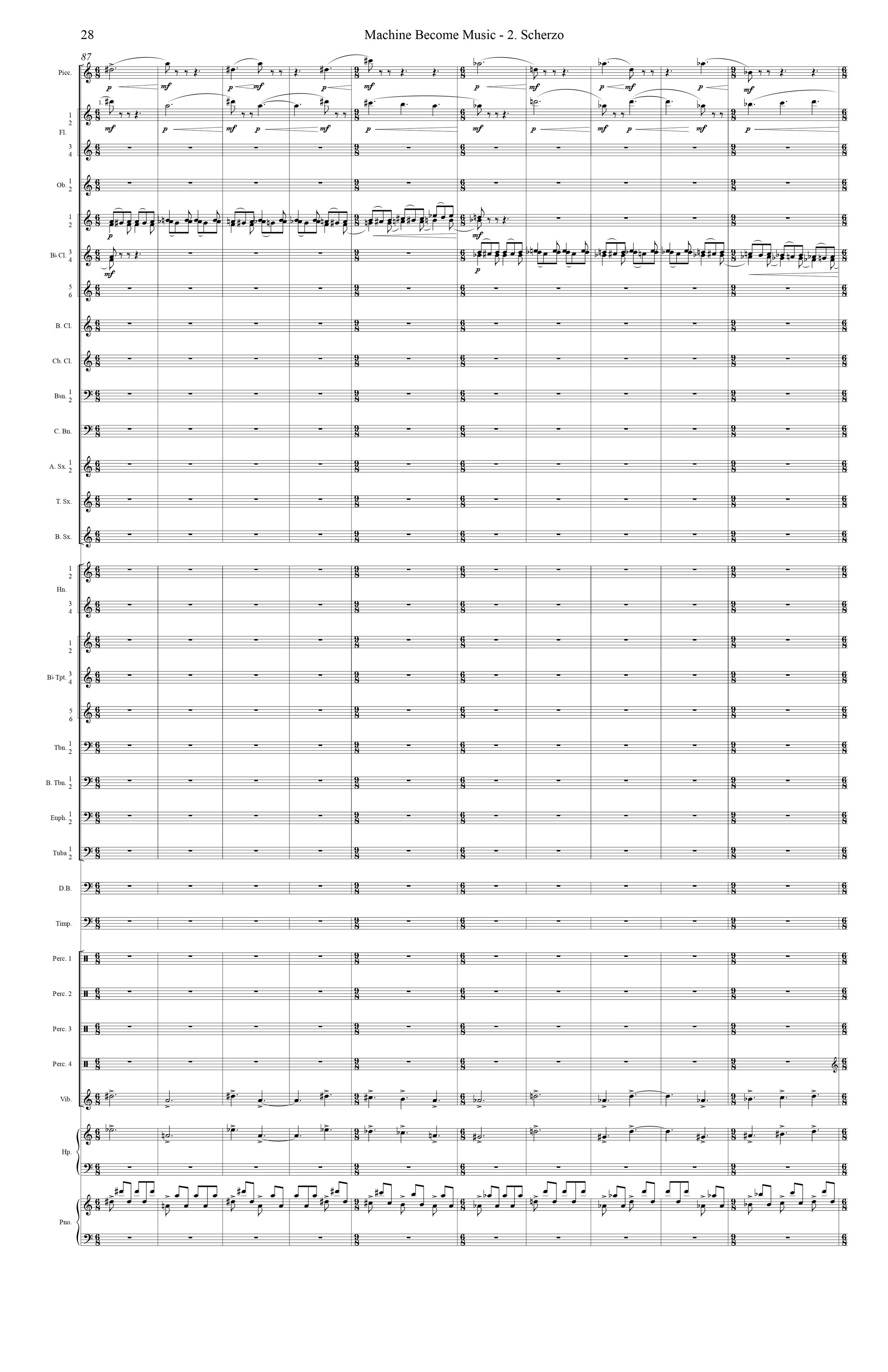

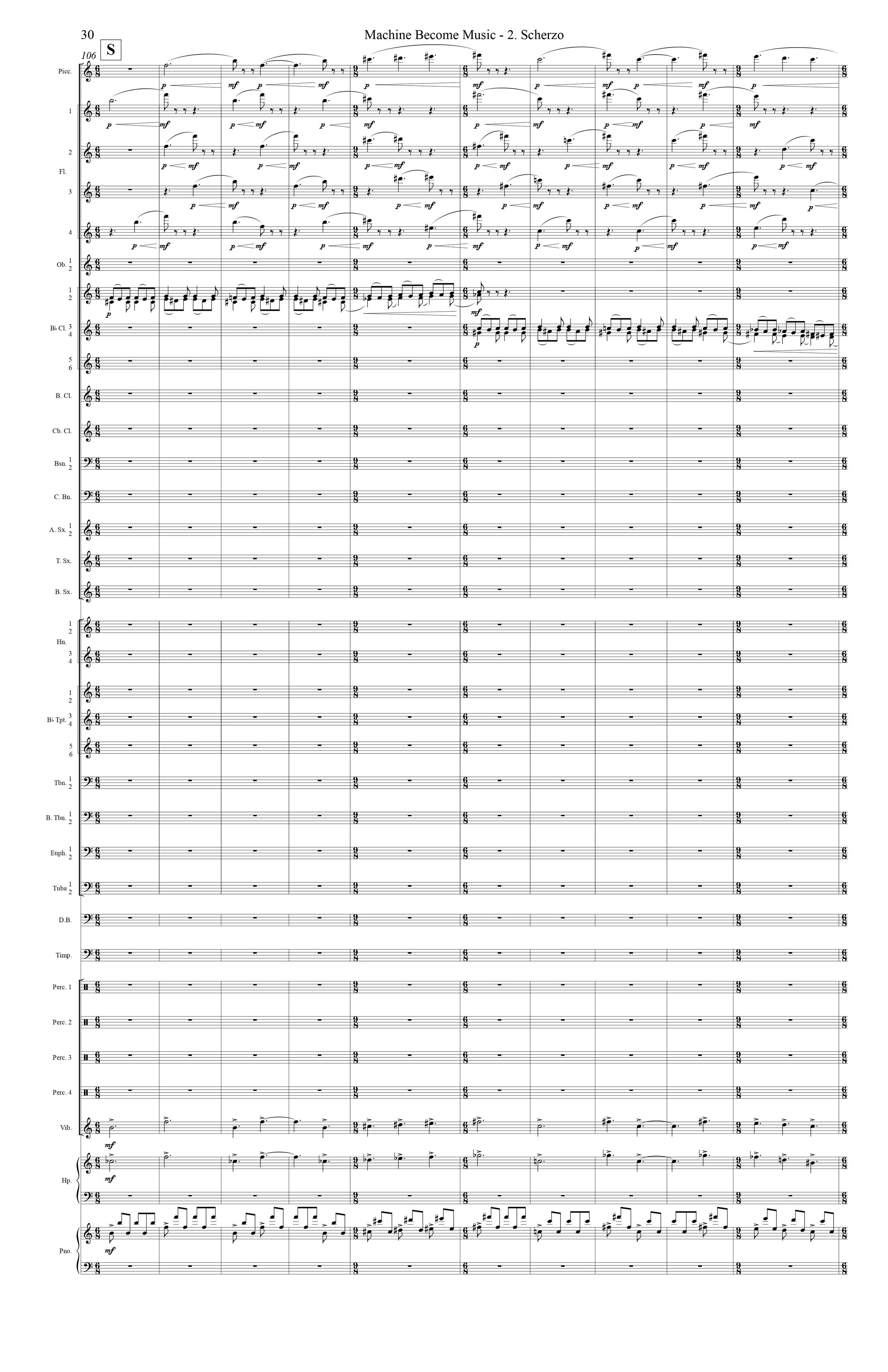

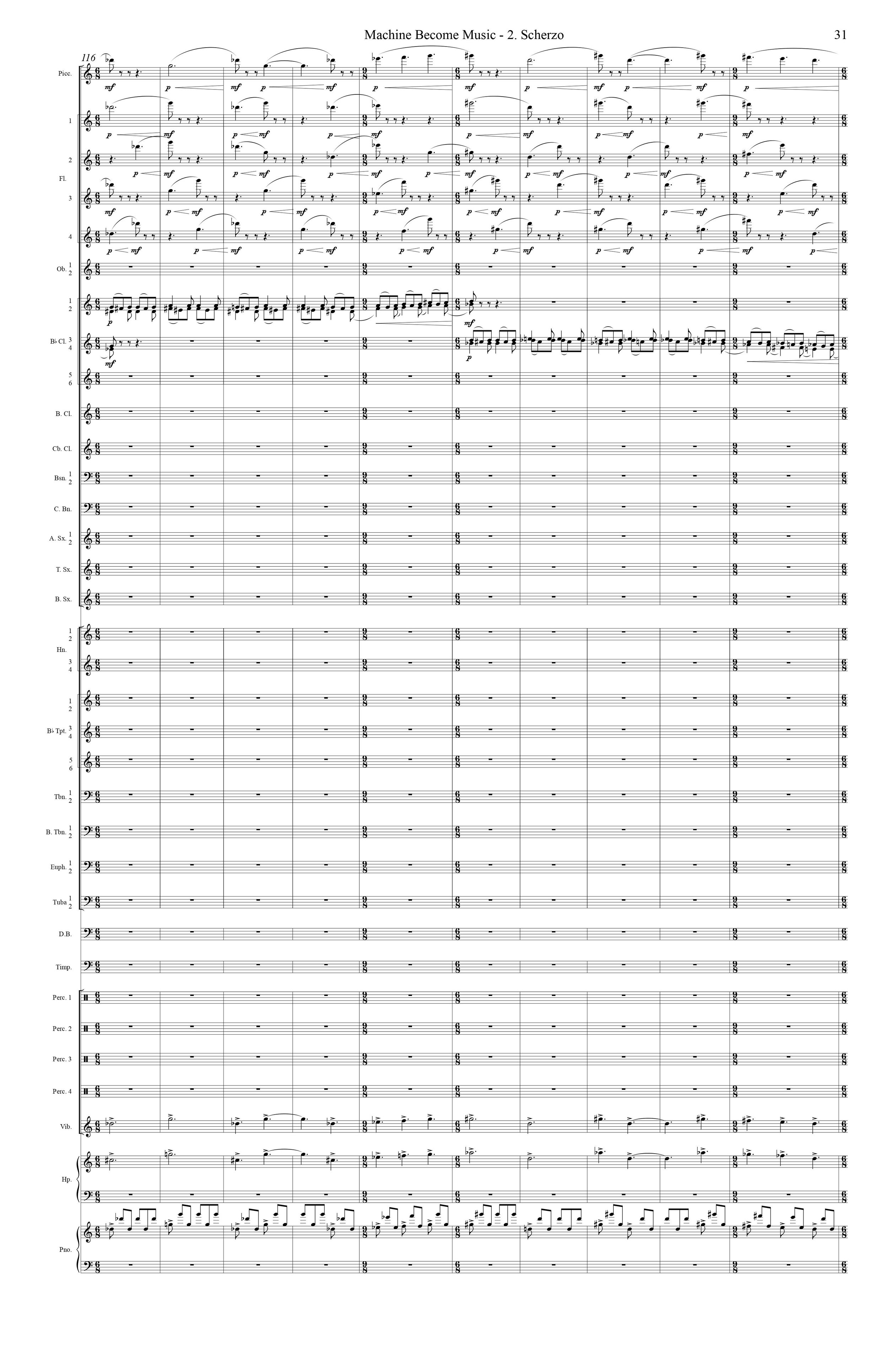

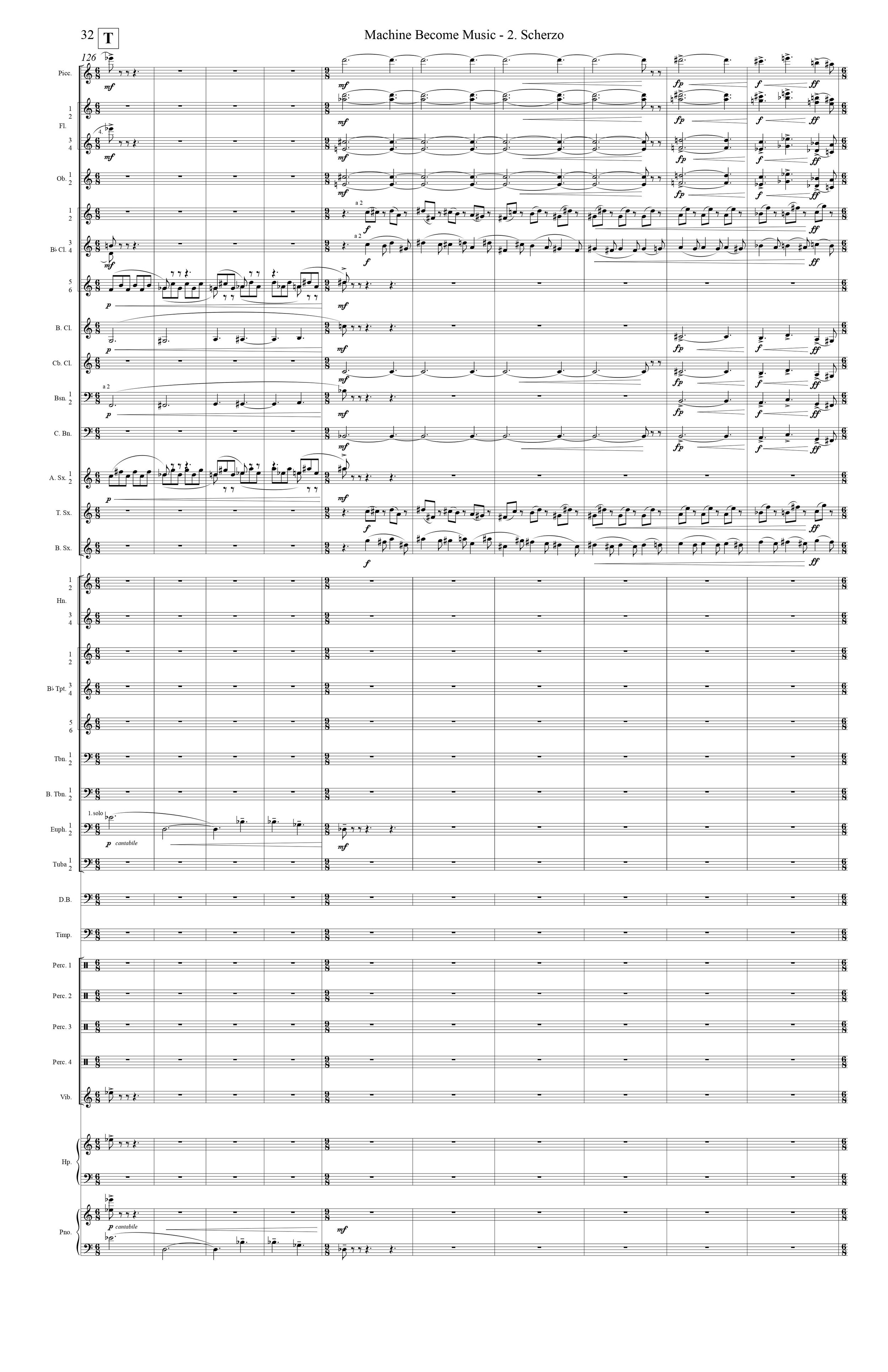

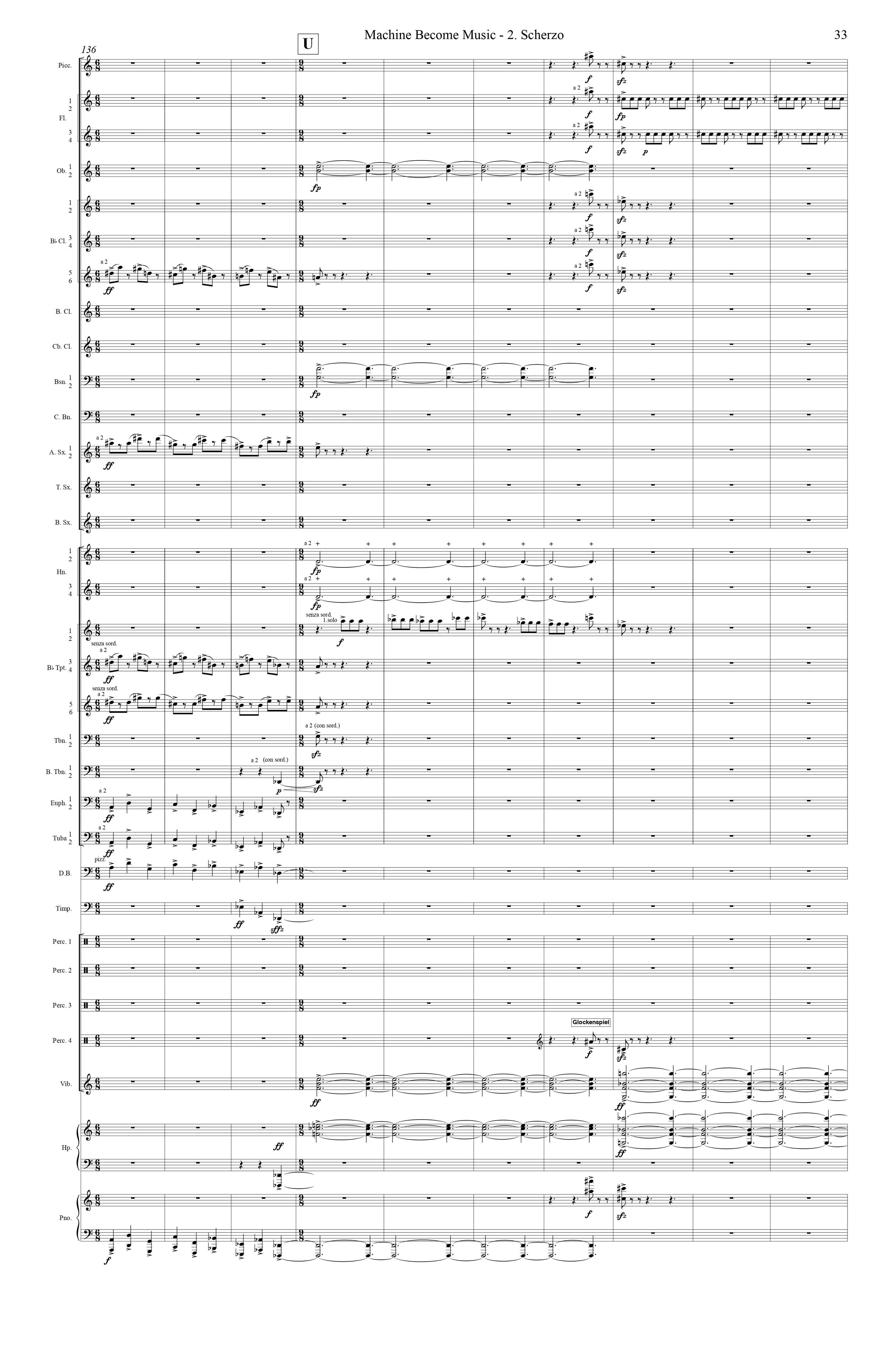

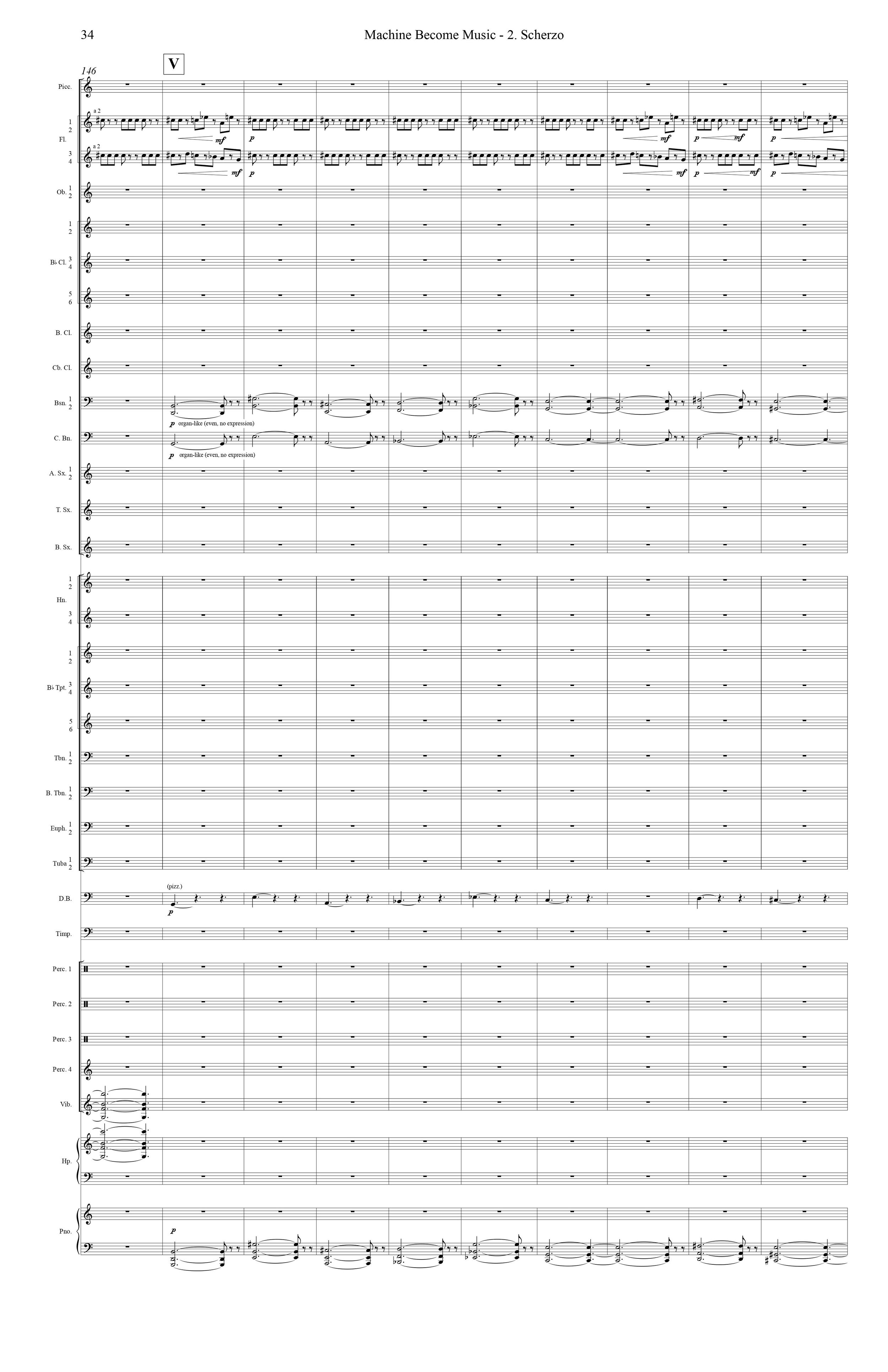

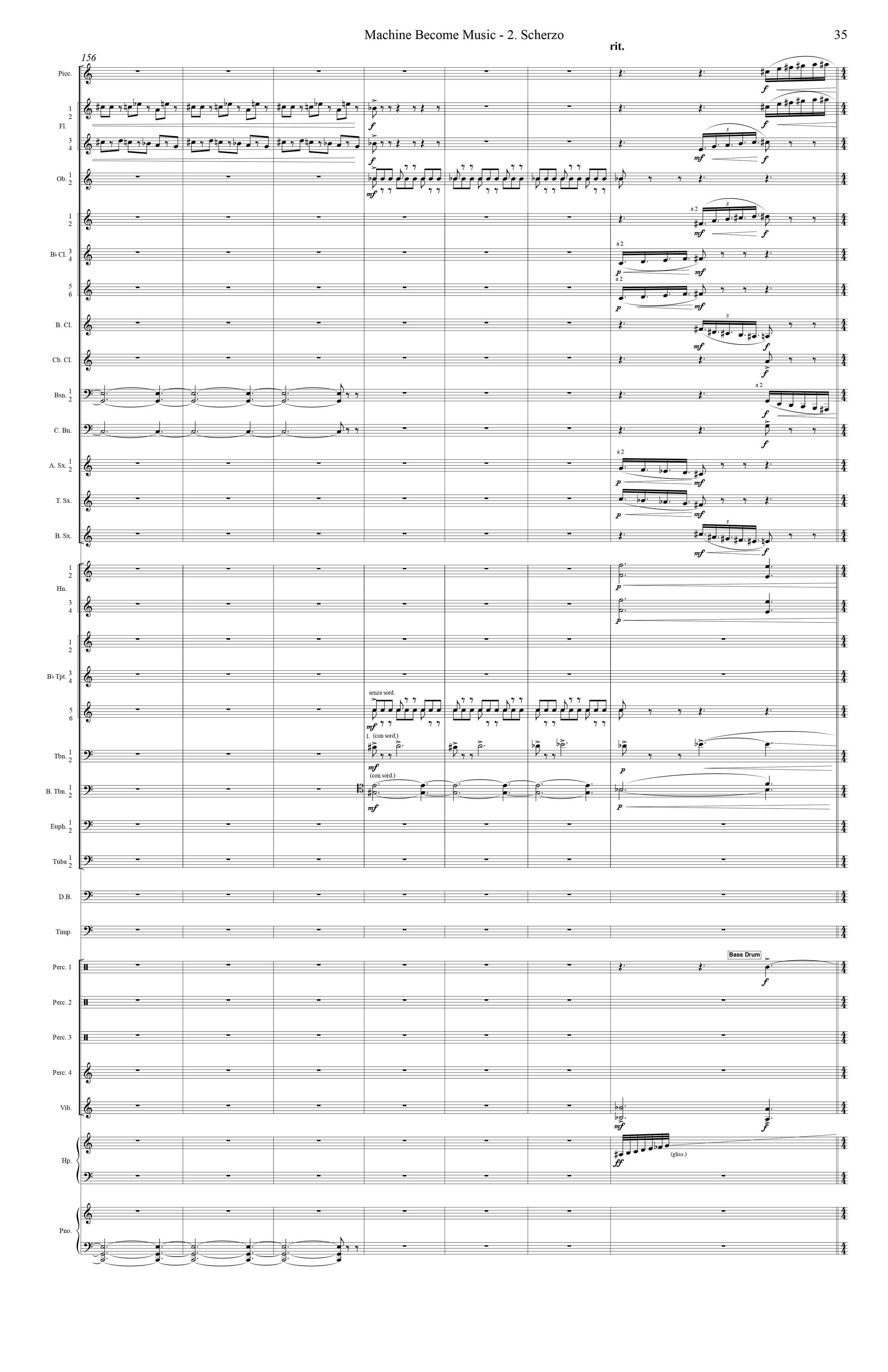

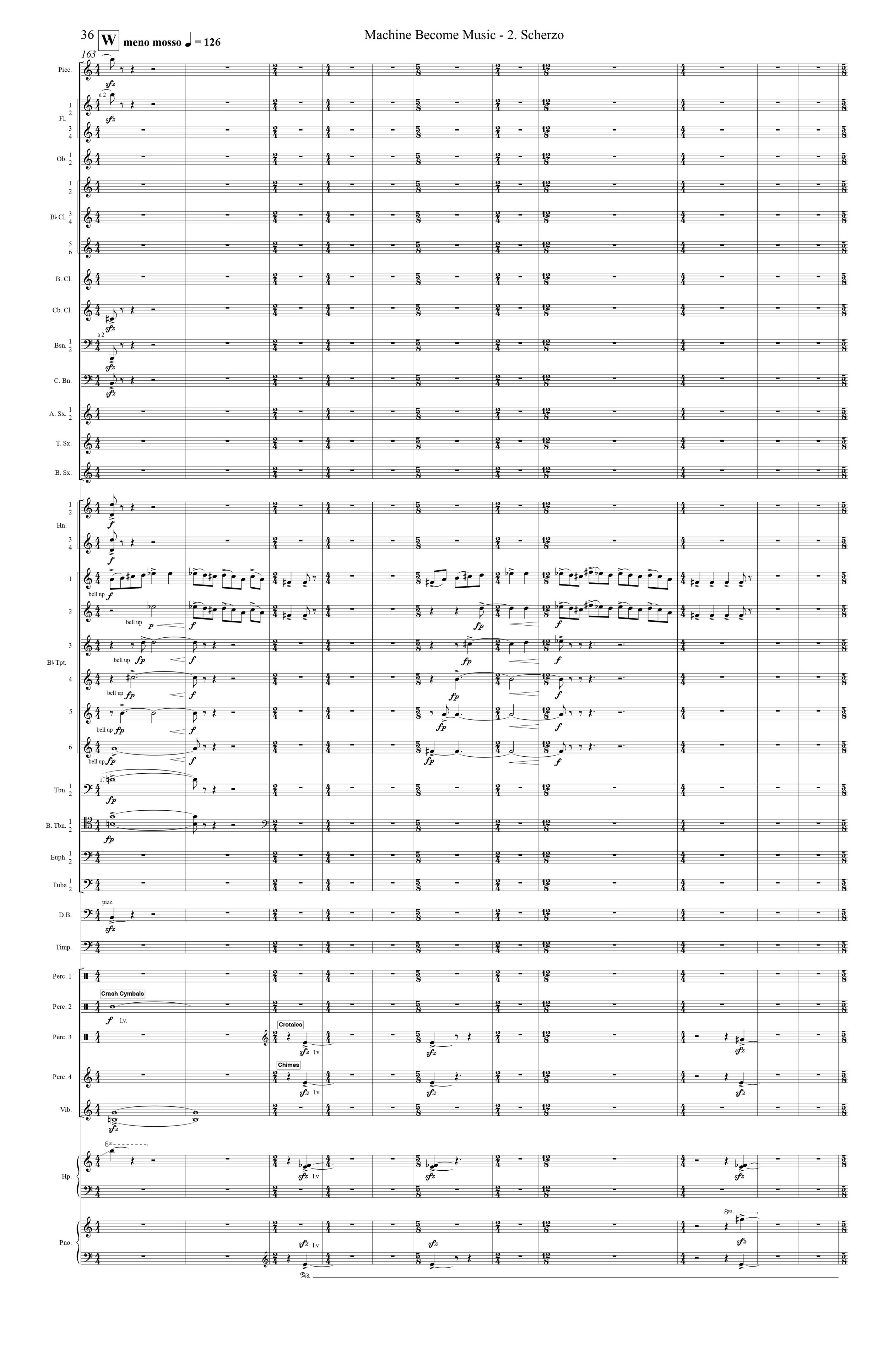

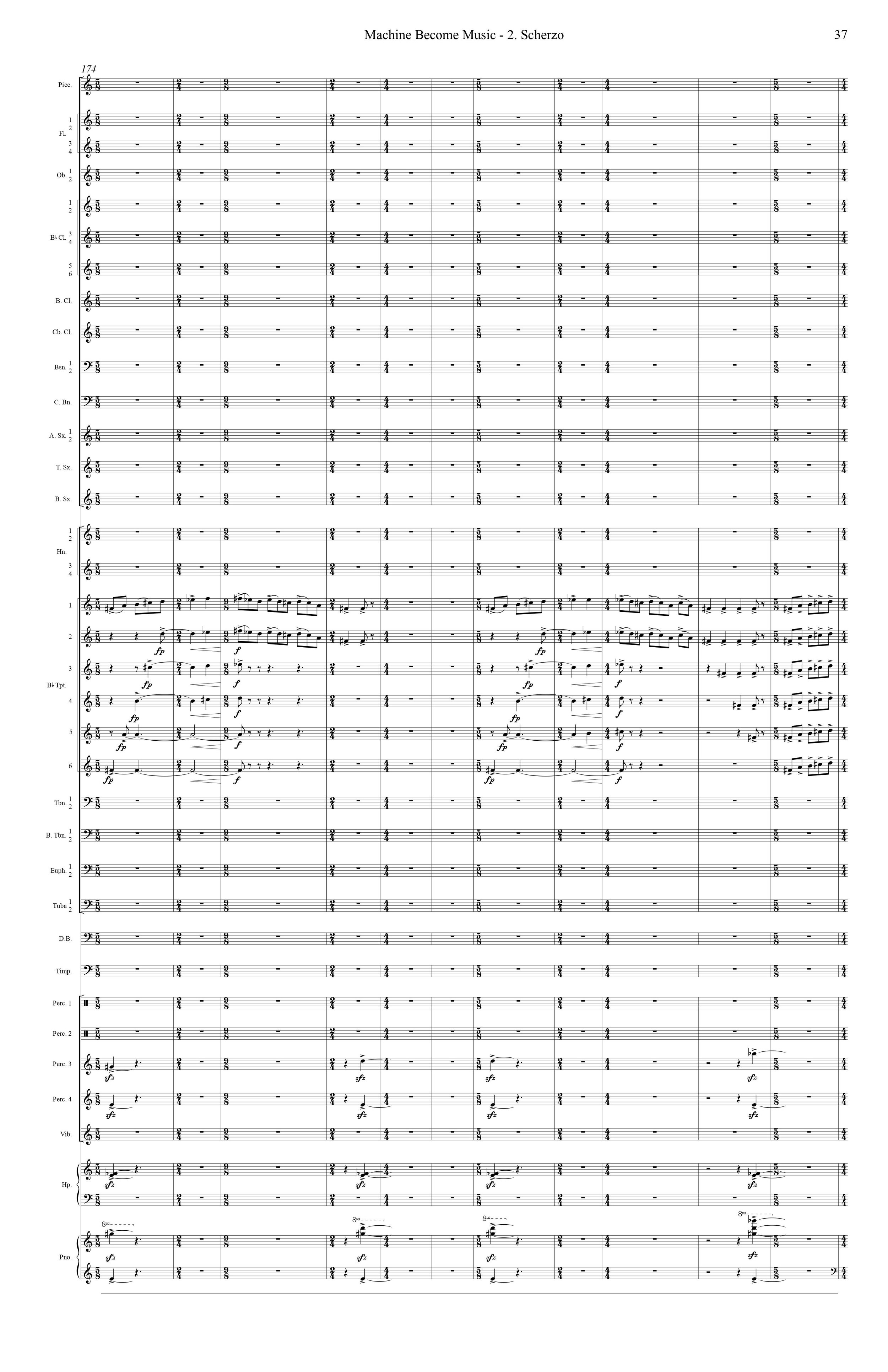

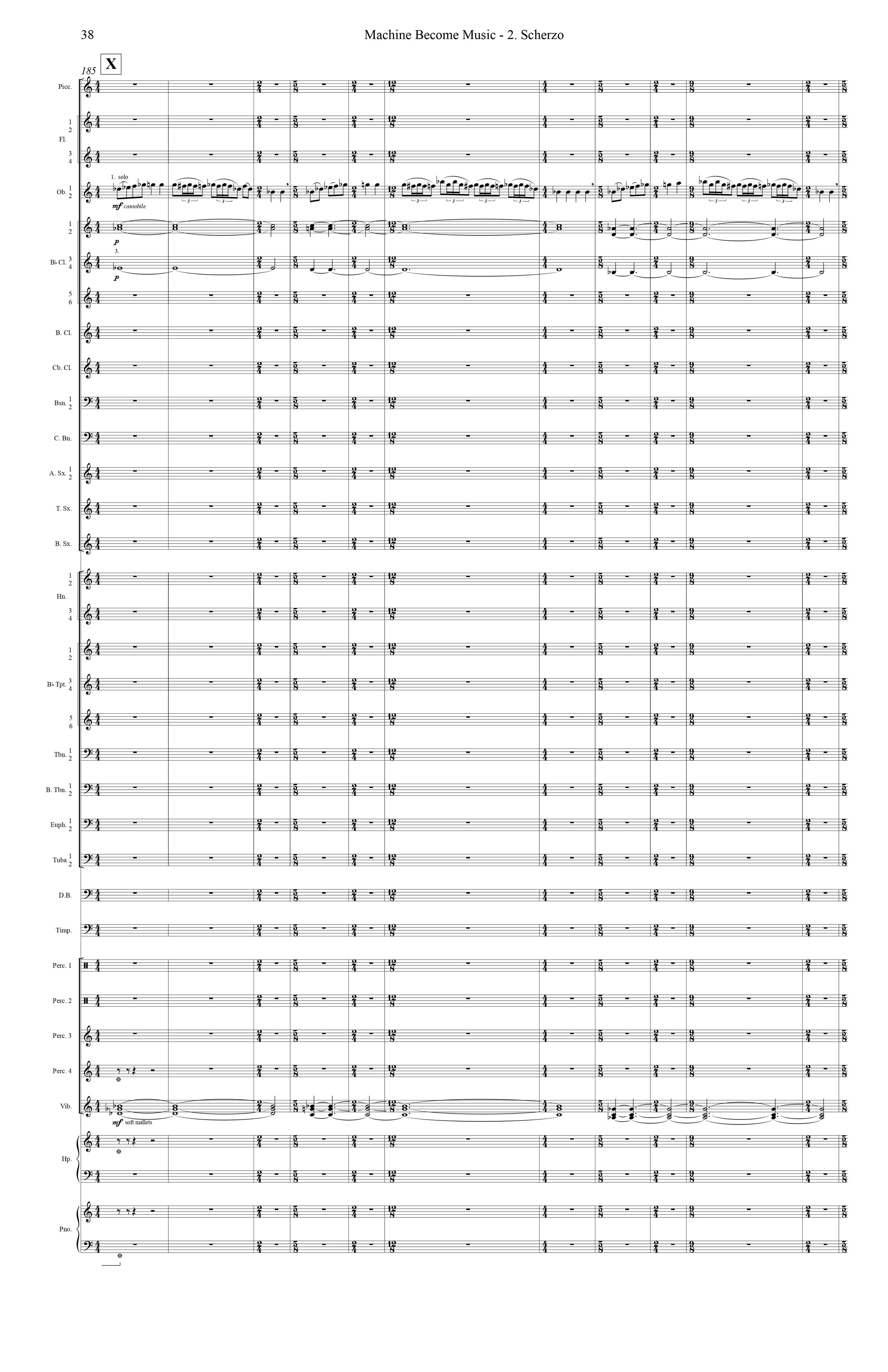

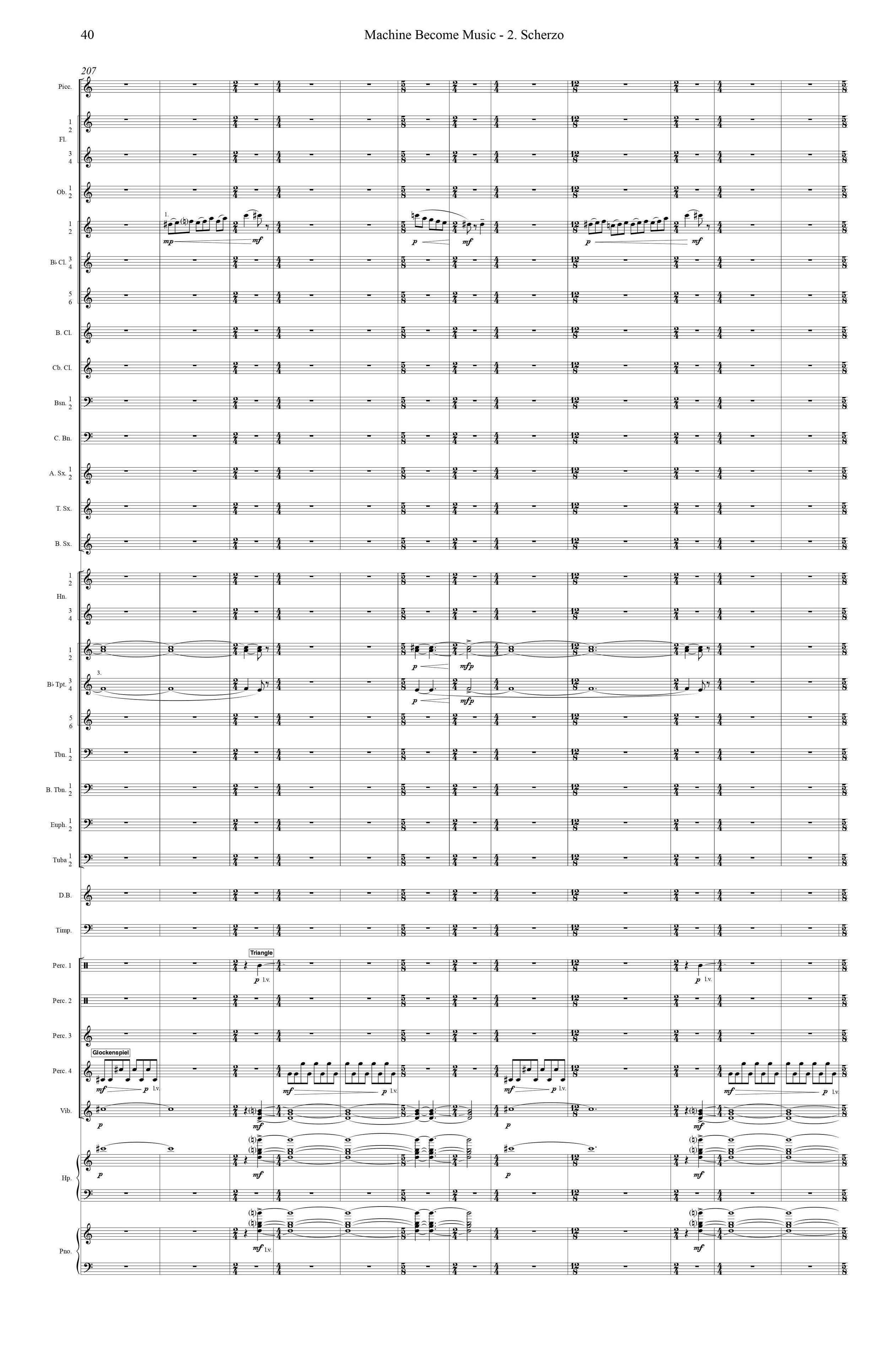

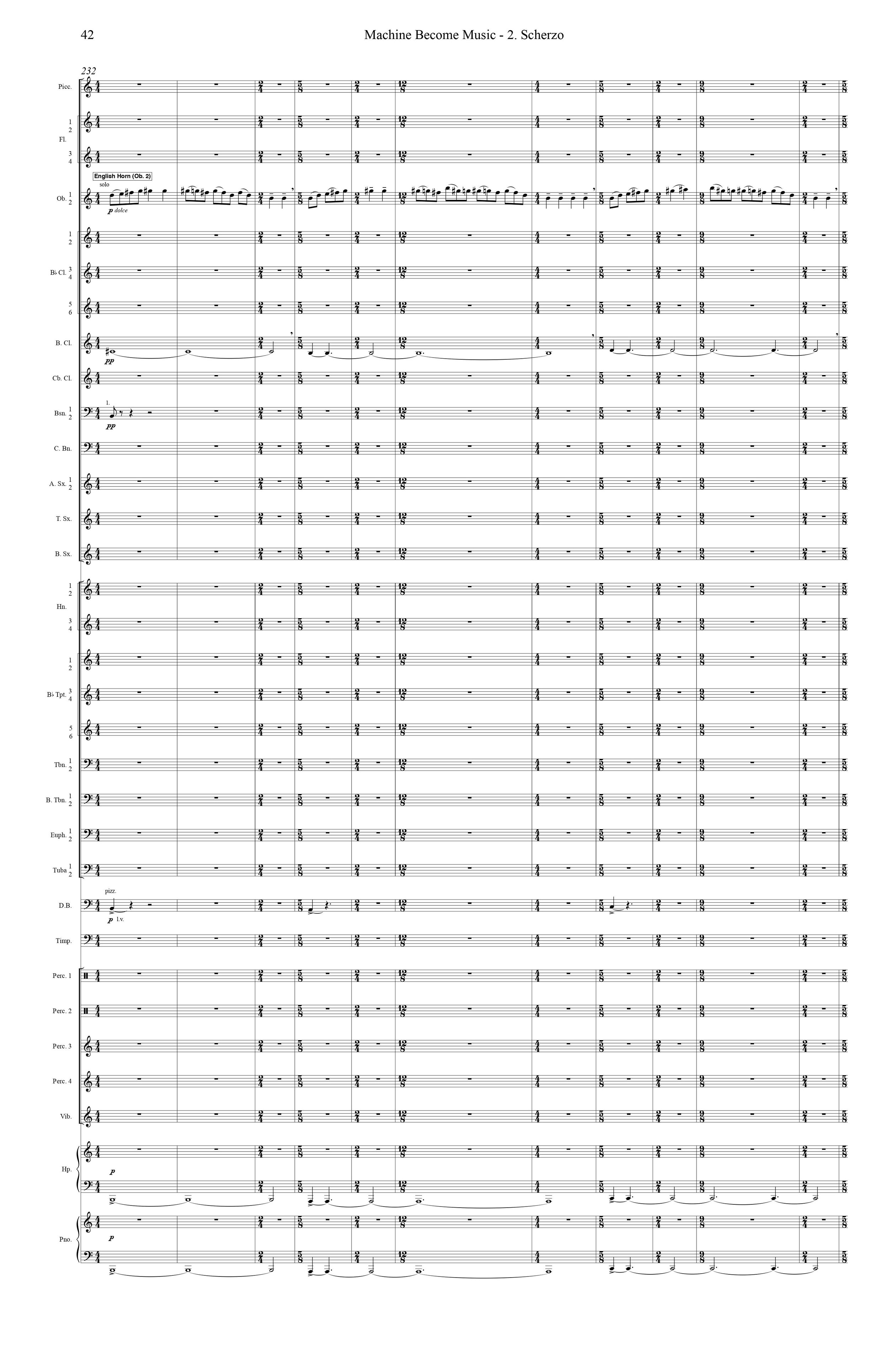

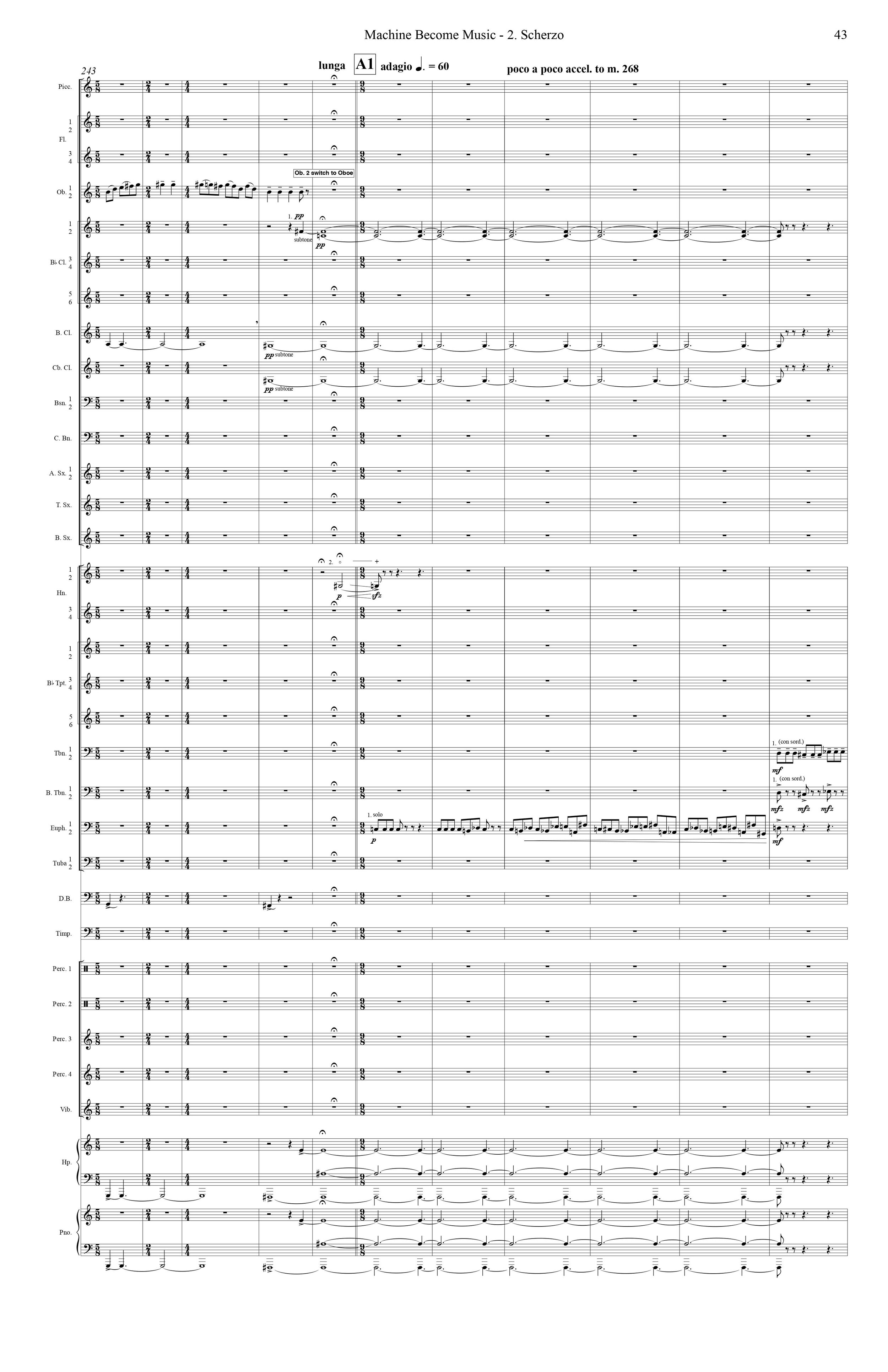

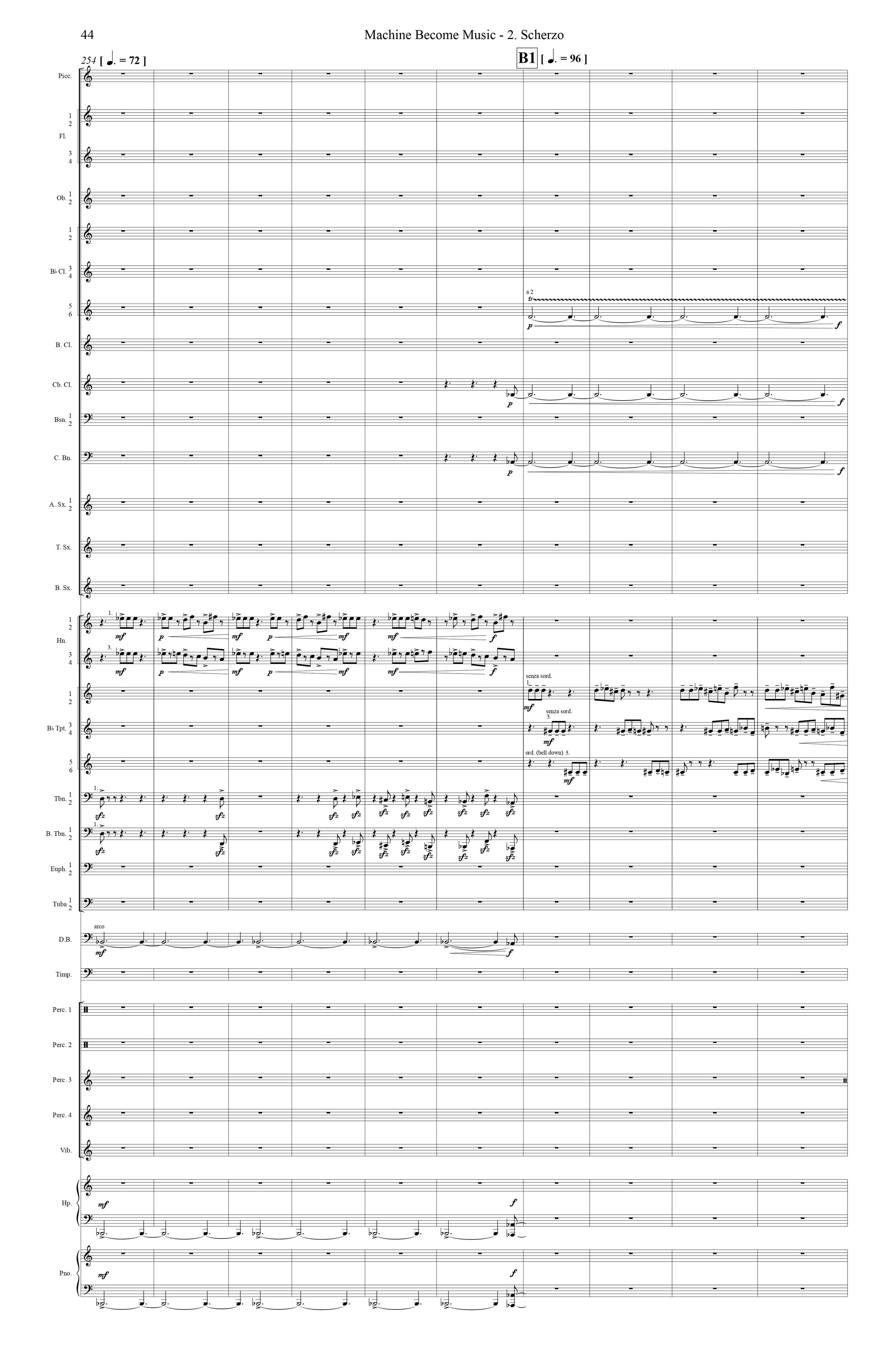

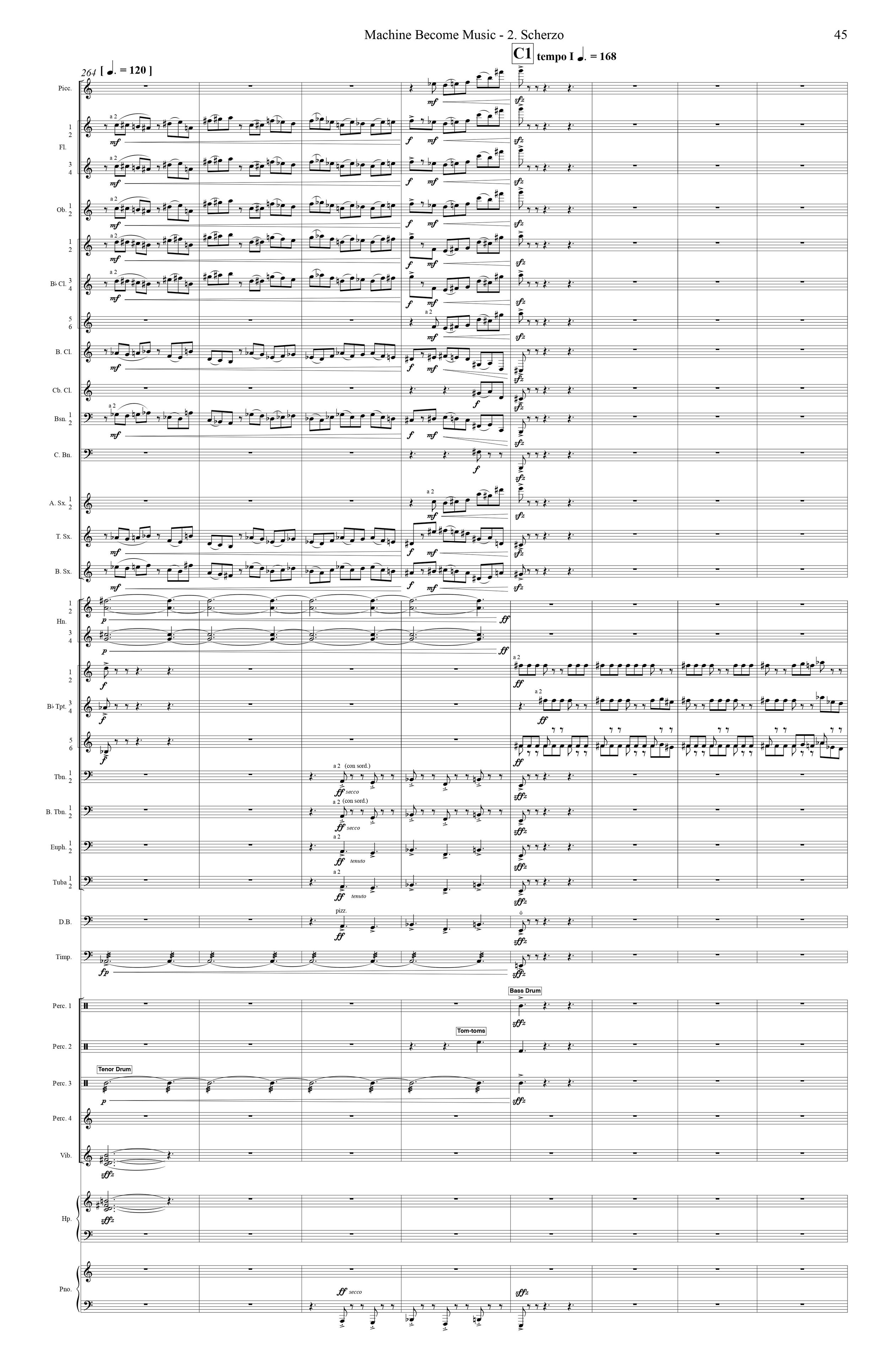

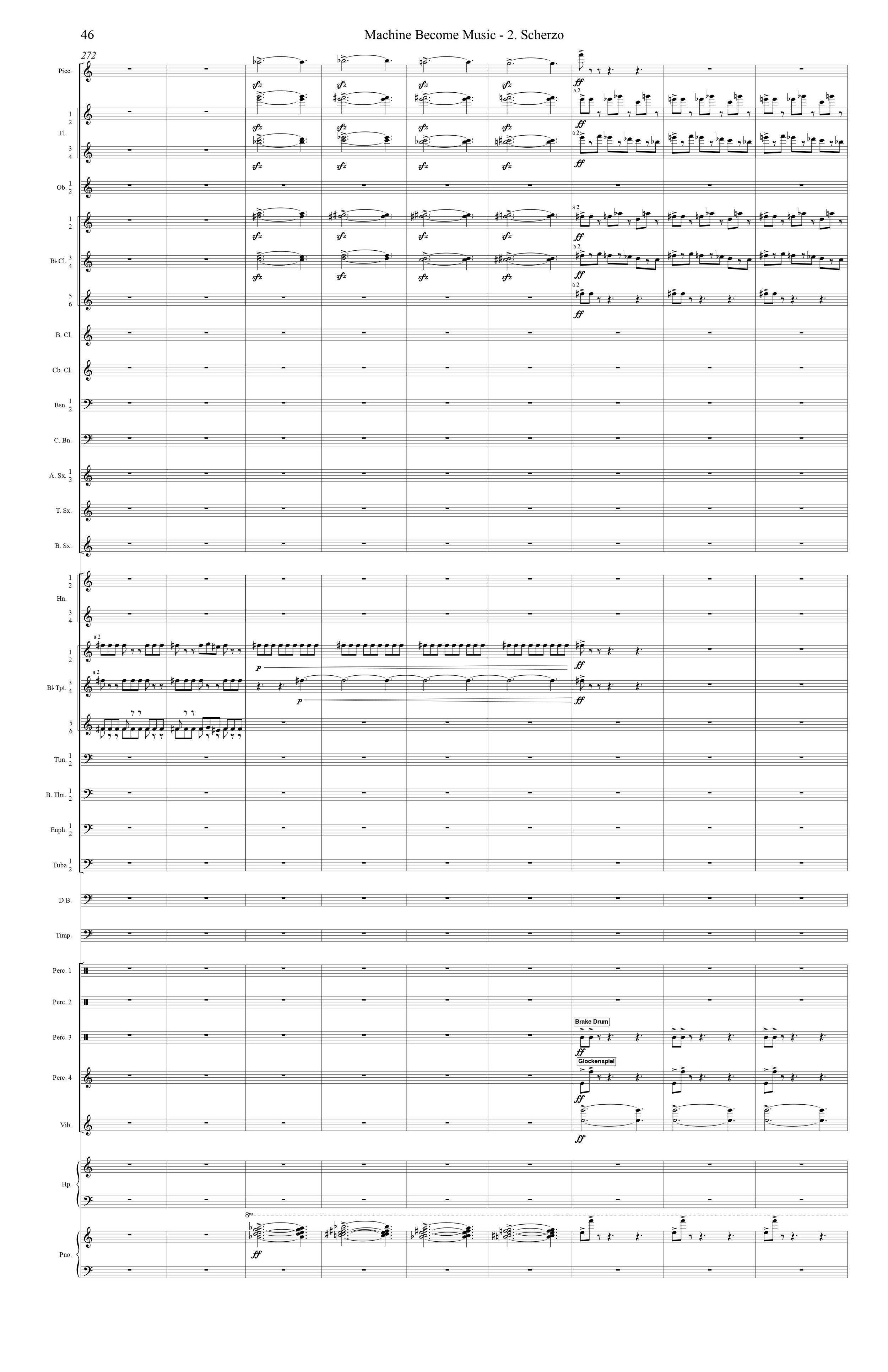

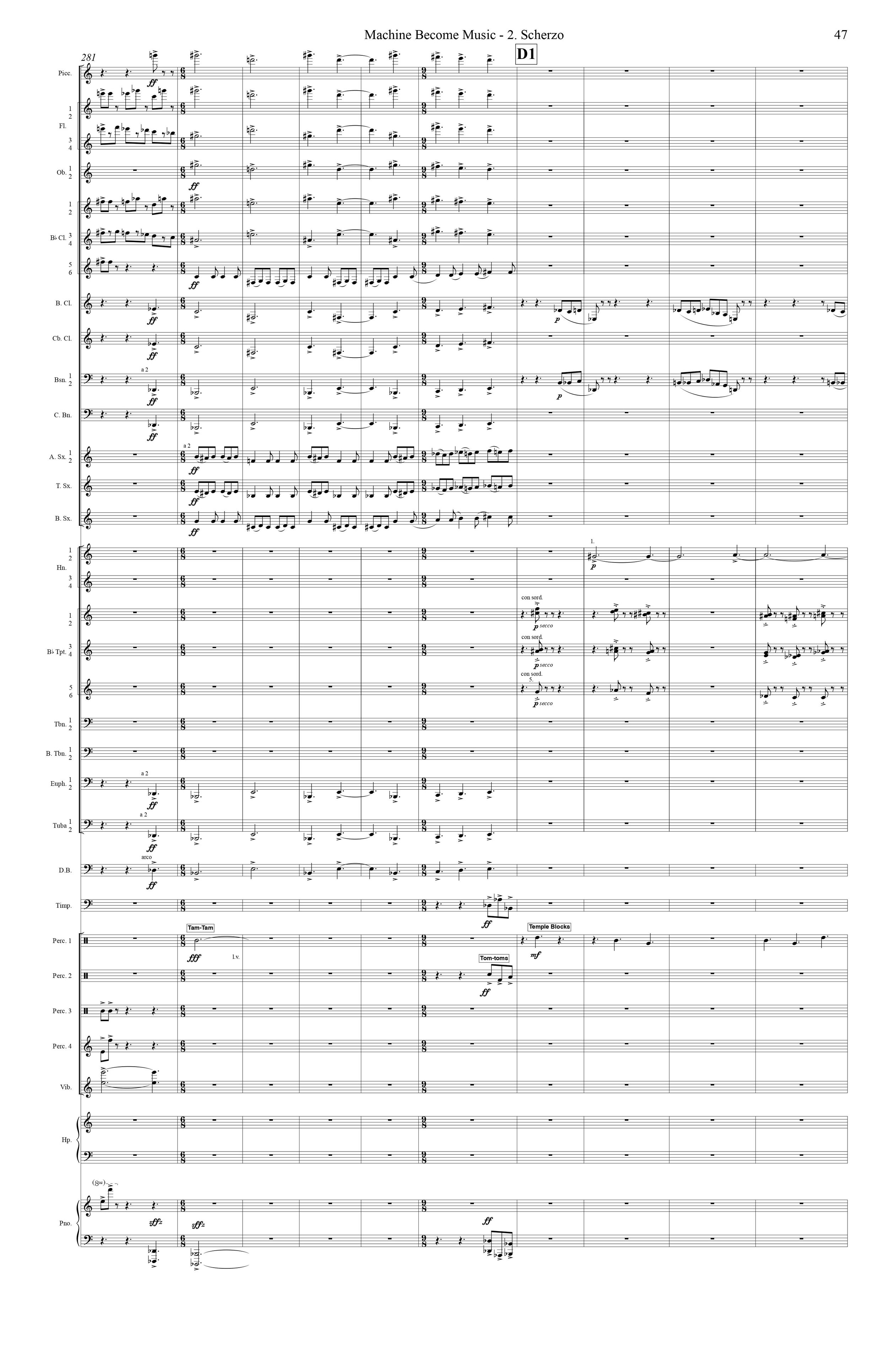

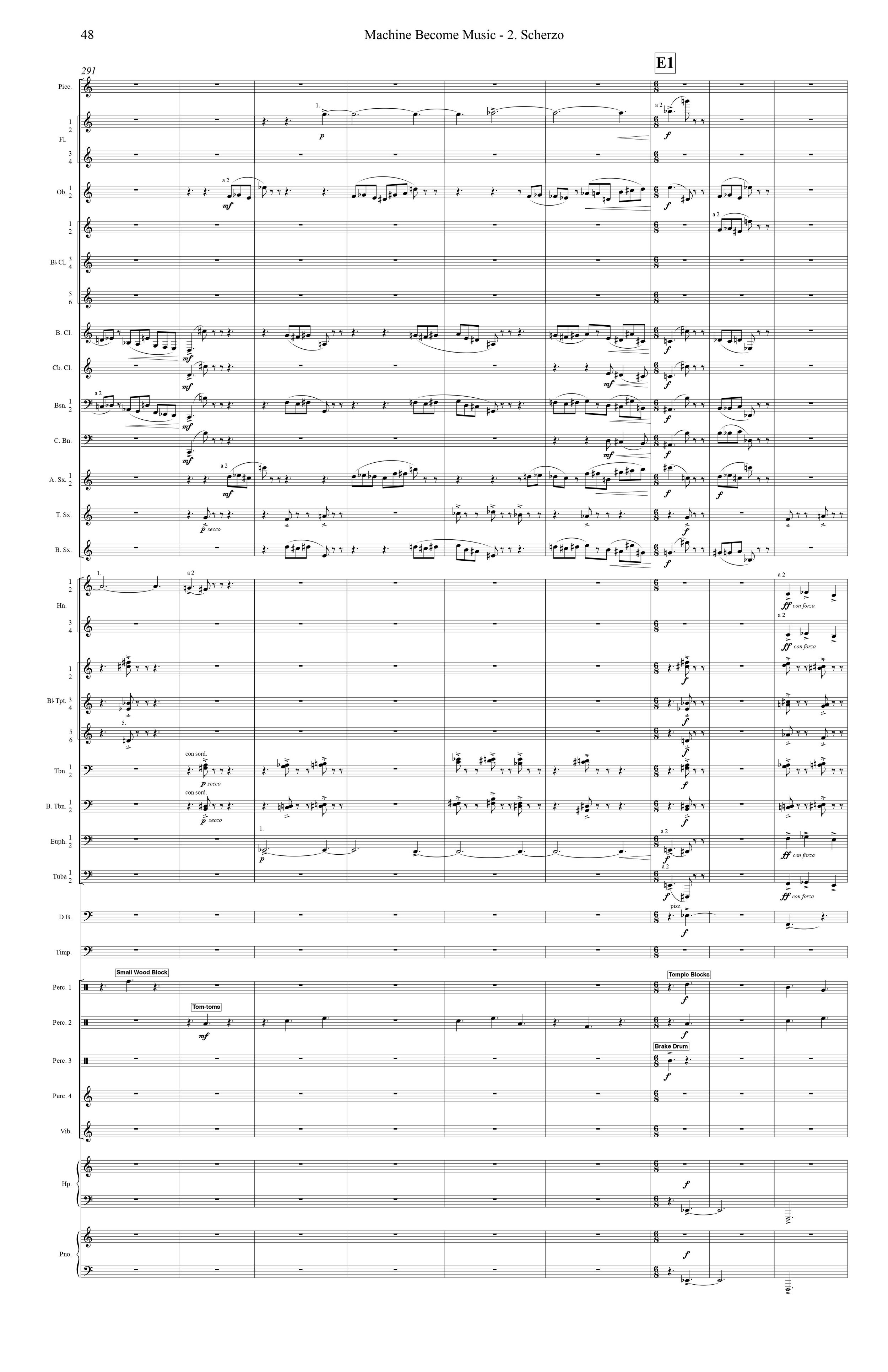

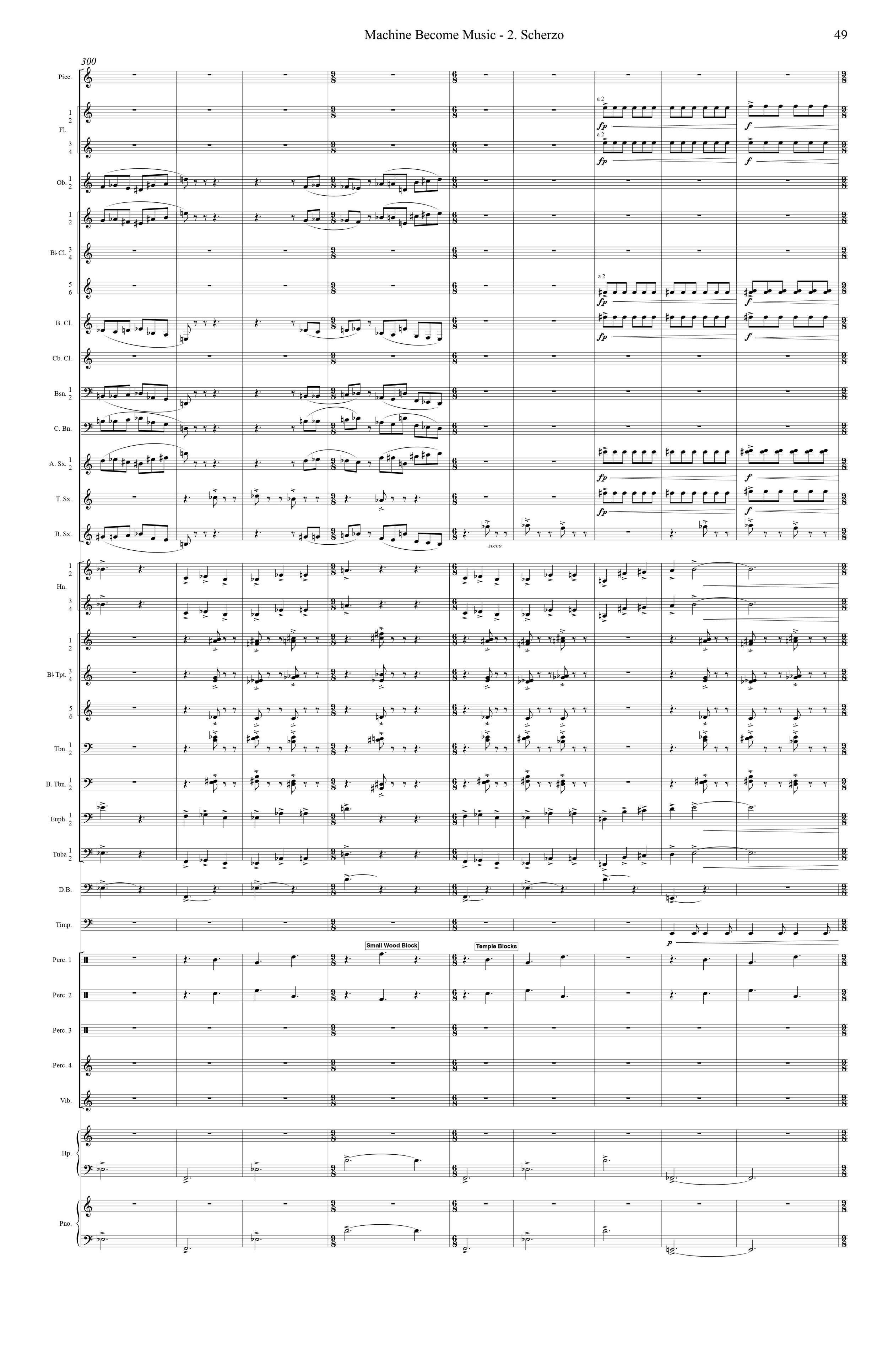

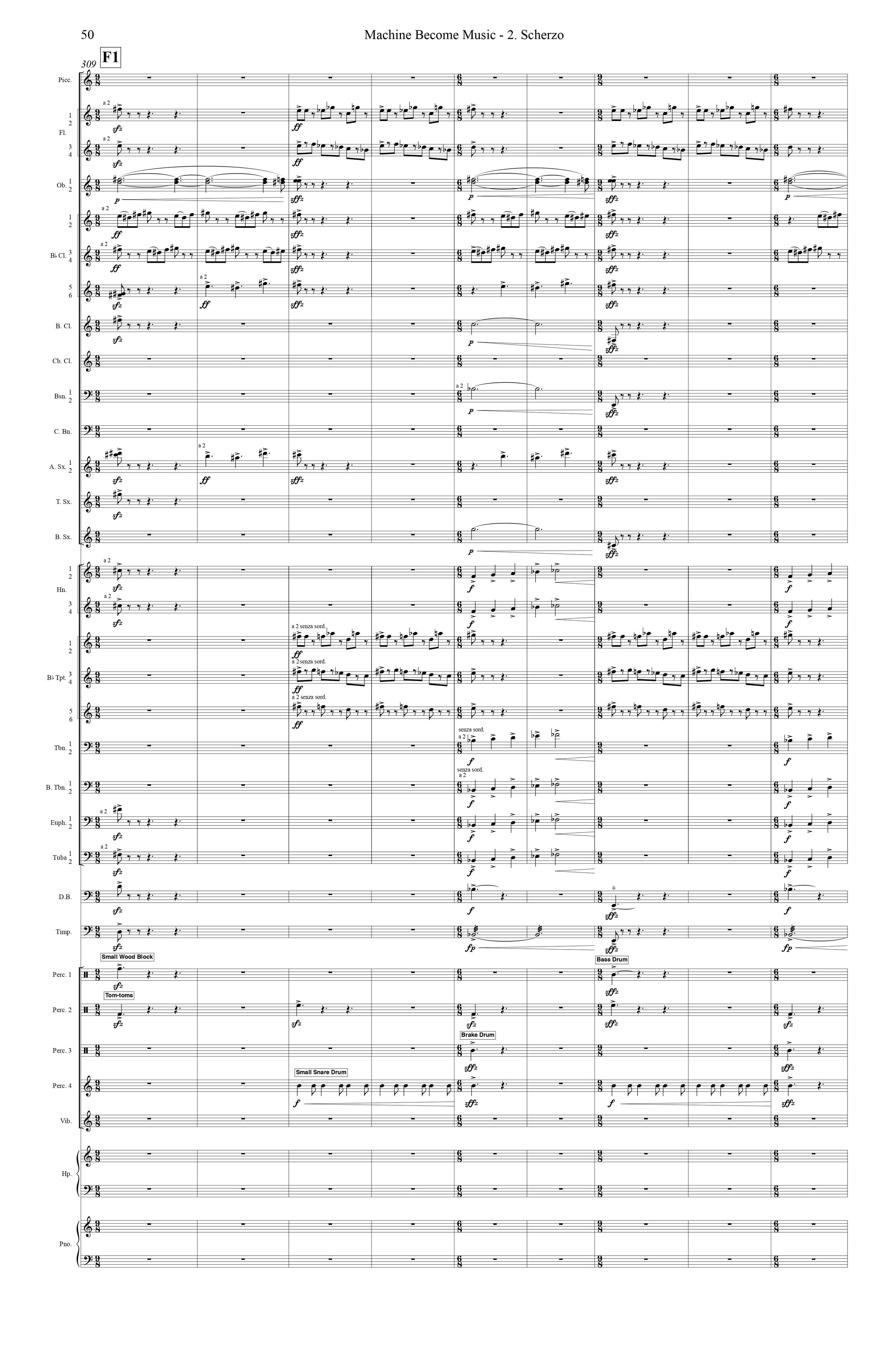

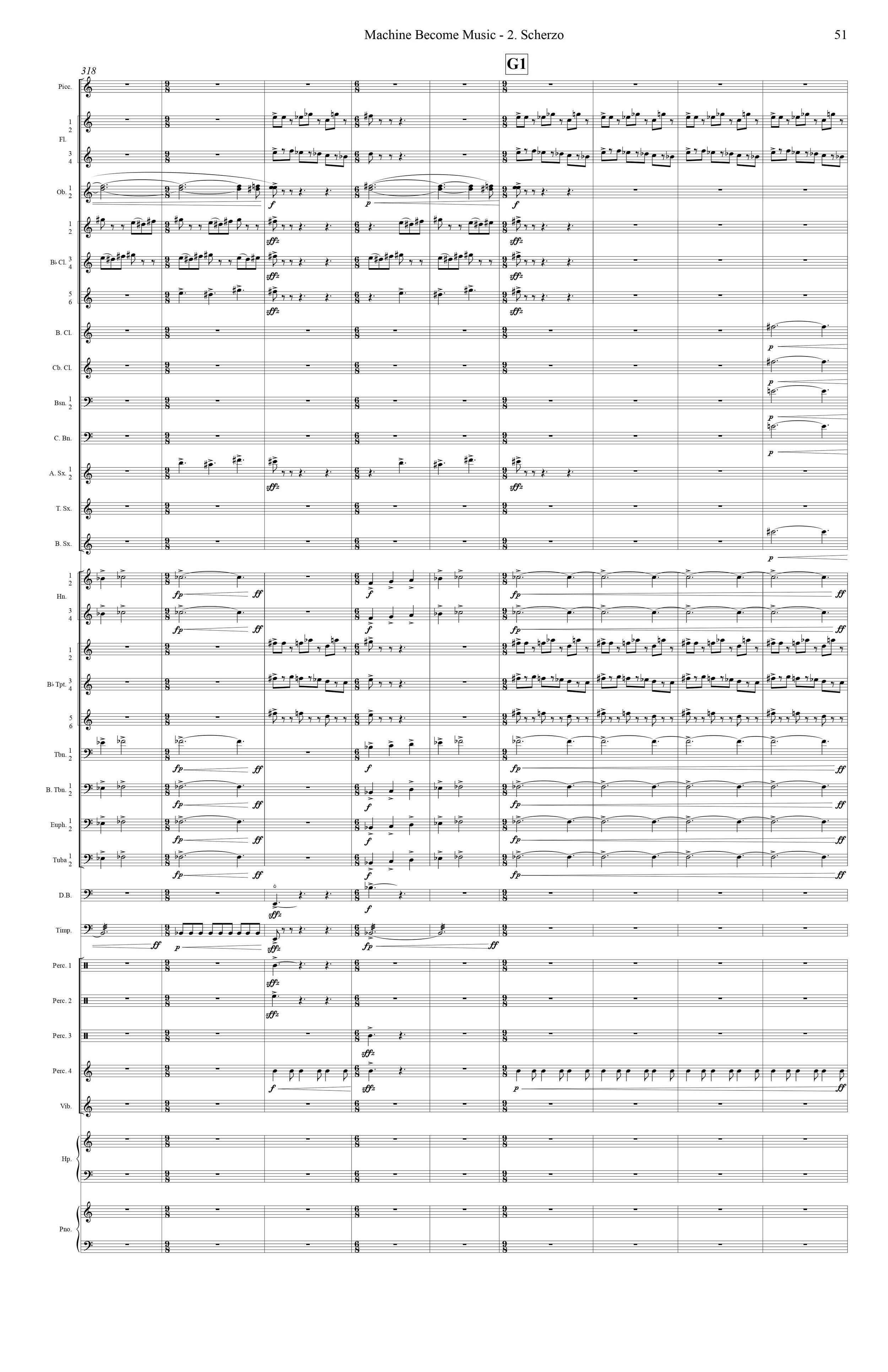

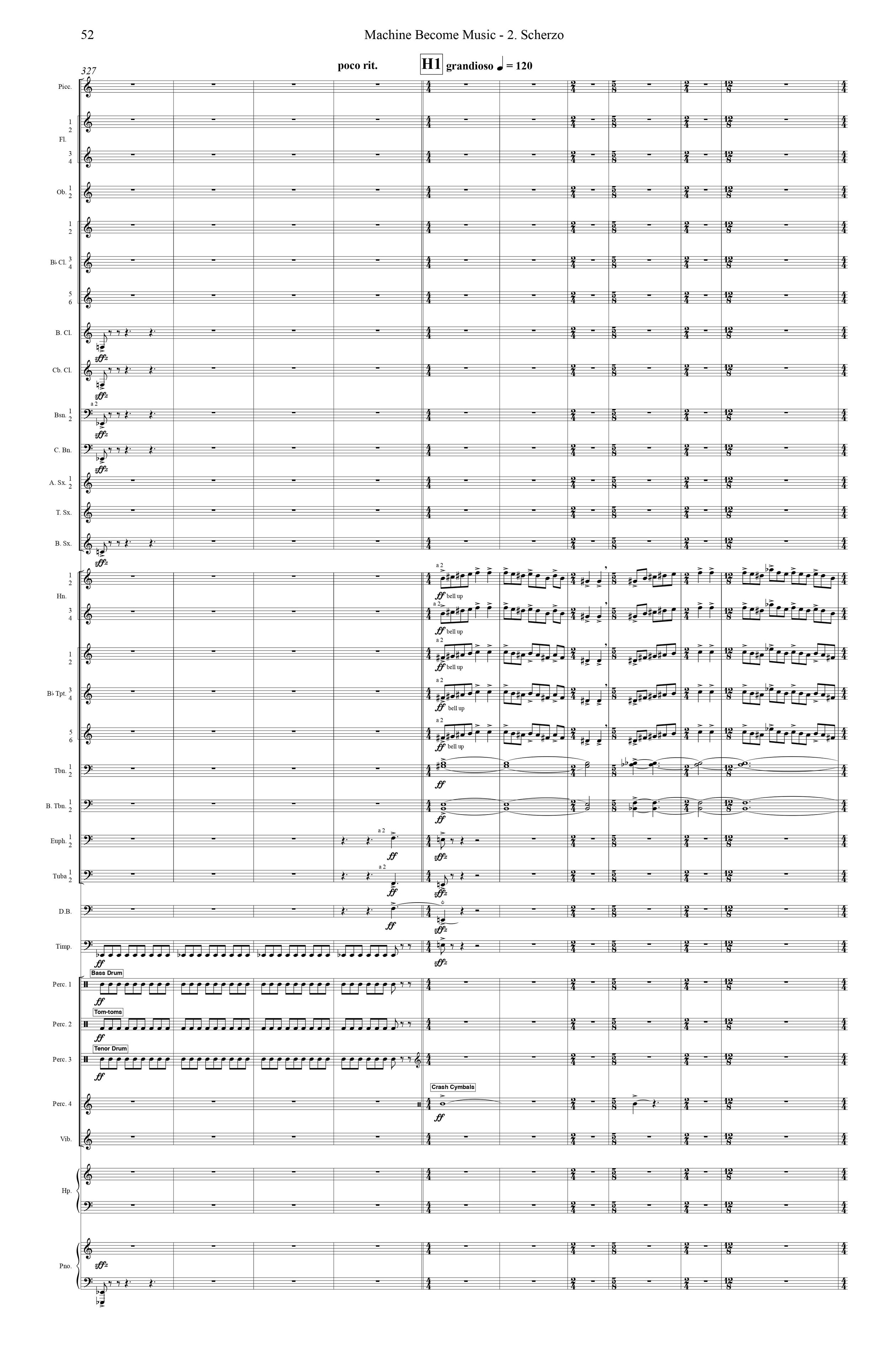

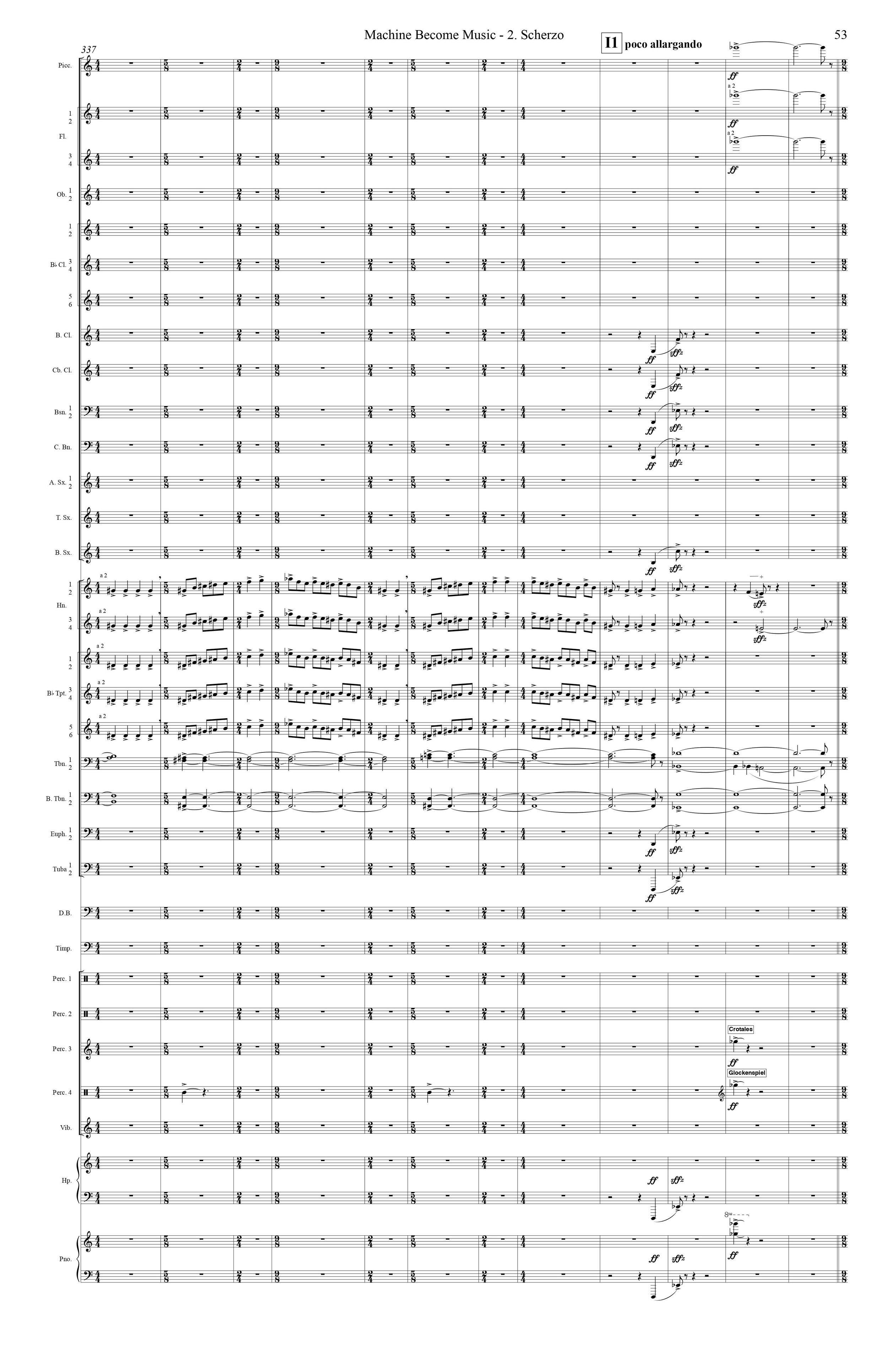

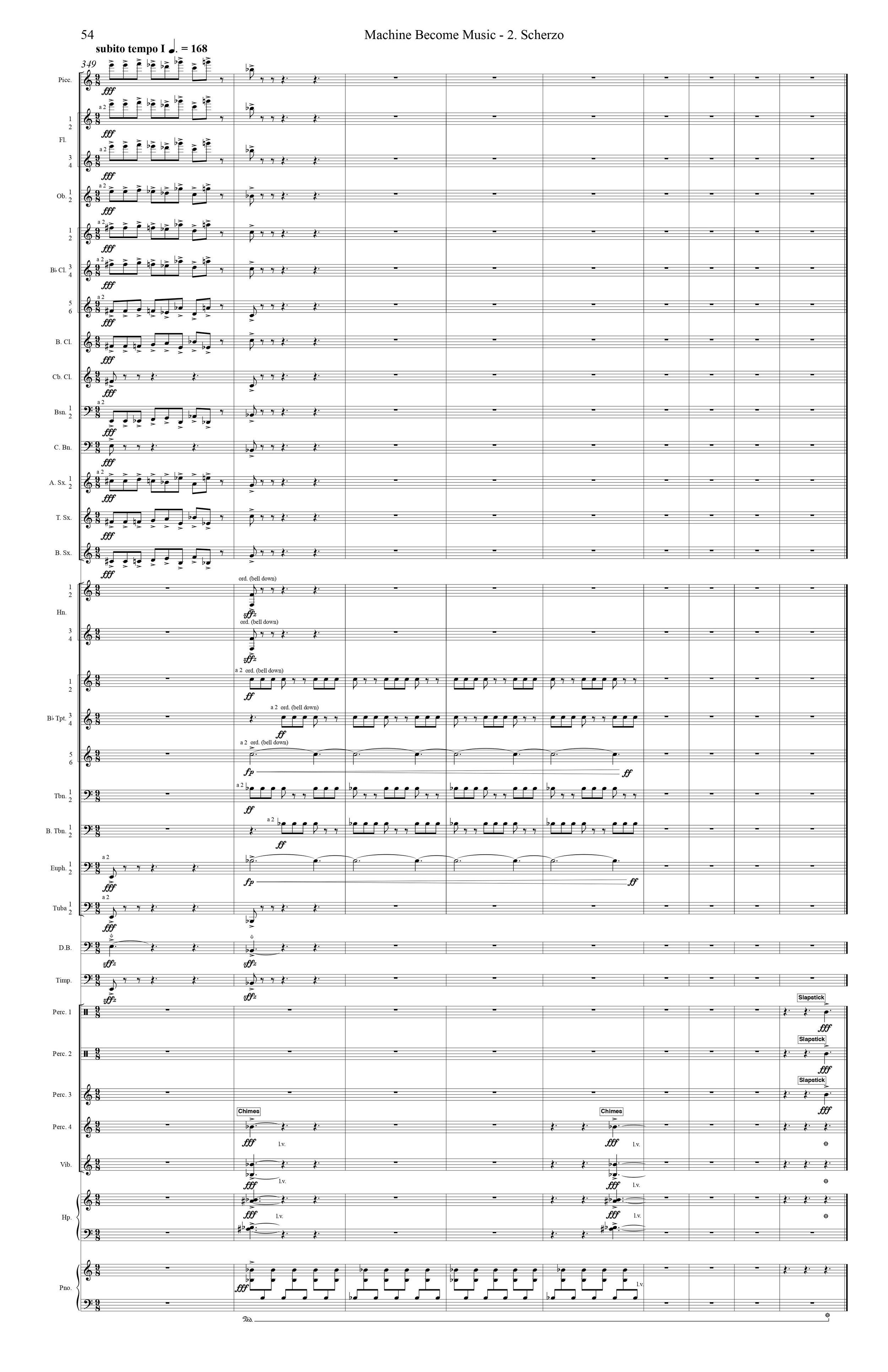

The second movement is a brisk scherzo. Here, the music captures the restless energy of a machine in a more general way. The agitated scherzo is offset by a more lyrical and dance-like middle section in which a simple melody is repeated several times, rotating through different harmonies. The machine slowly starts back up as the scherzo music returns and is mashed together with the lyrical melody, bringing the movement to a stop with a bang.

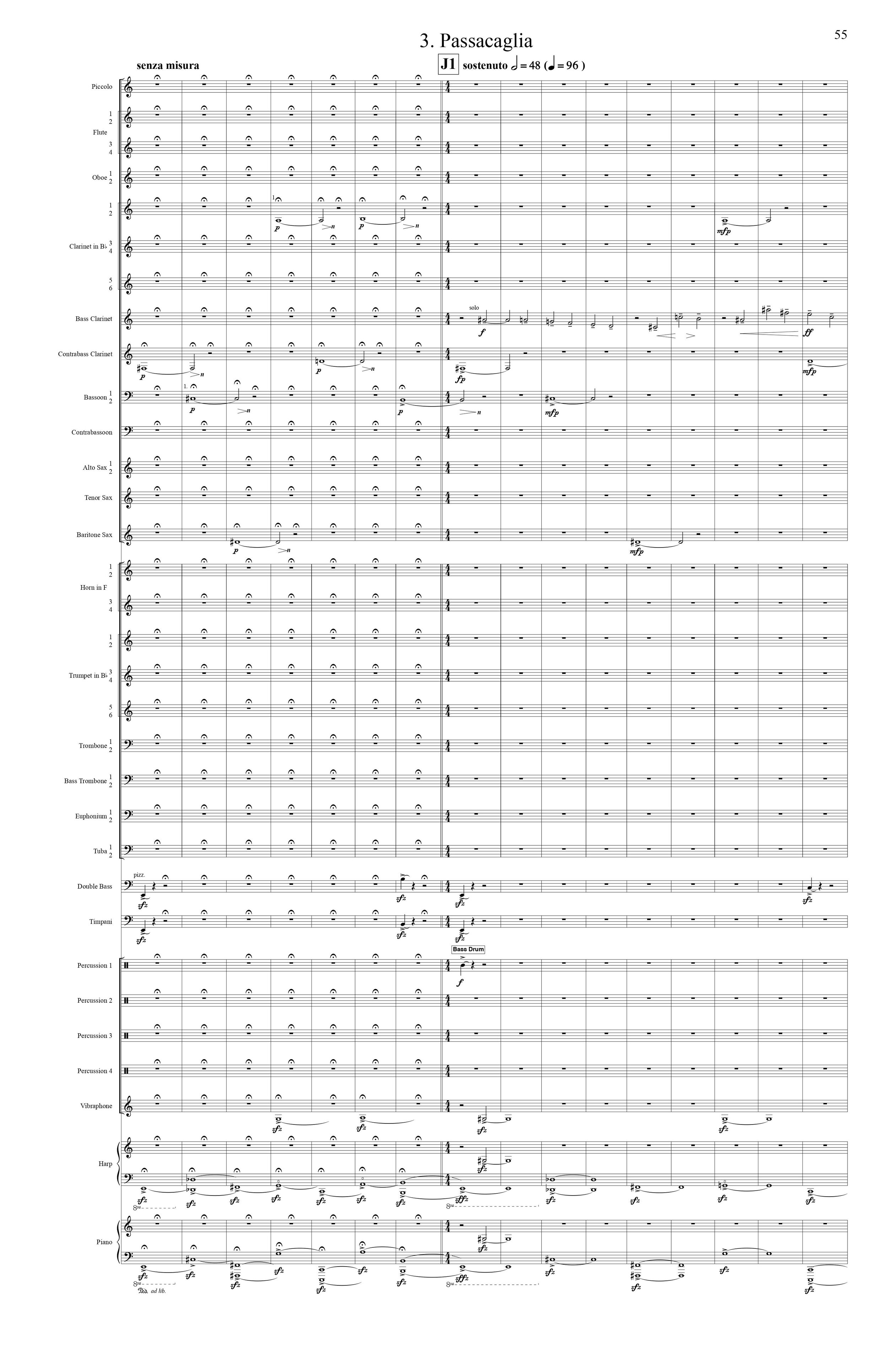

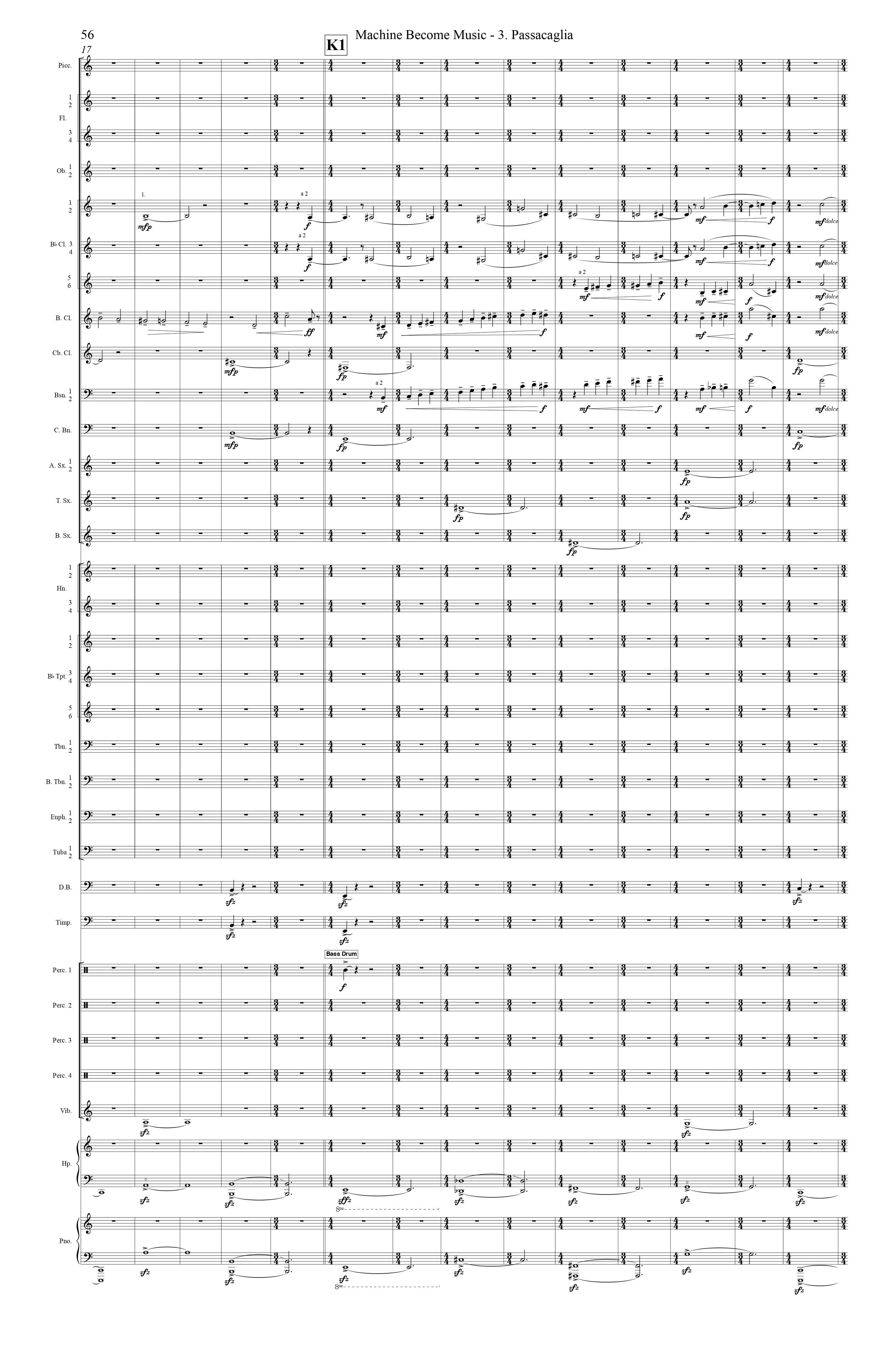

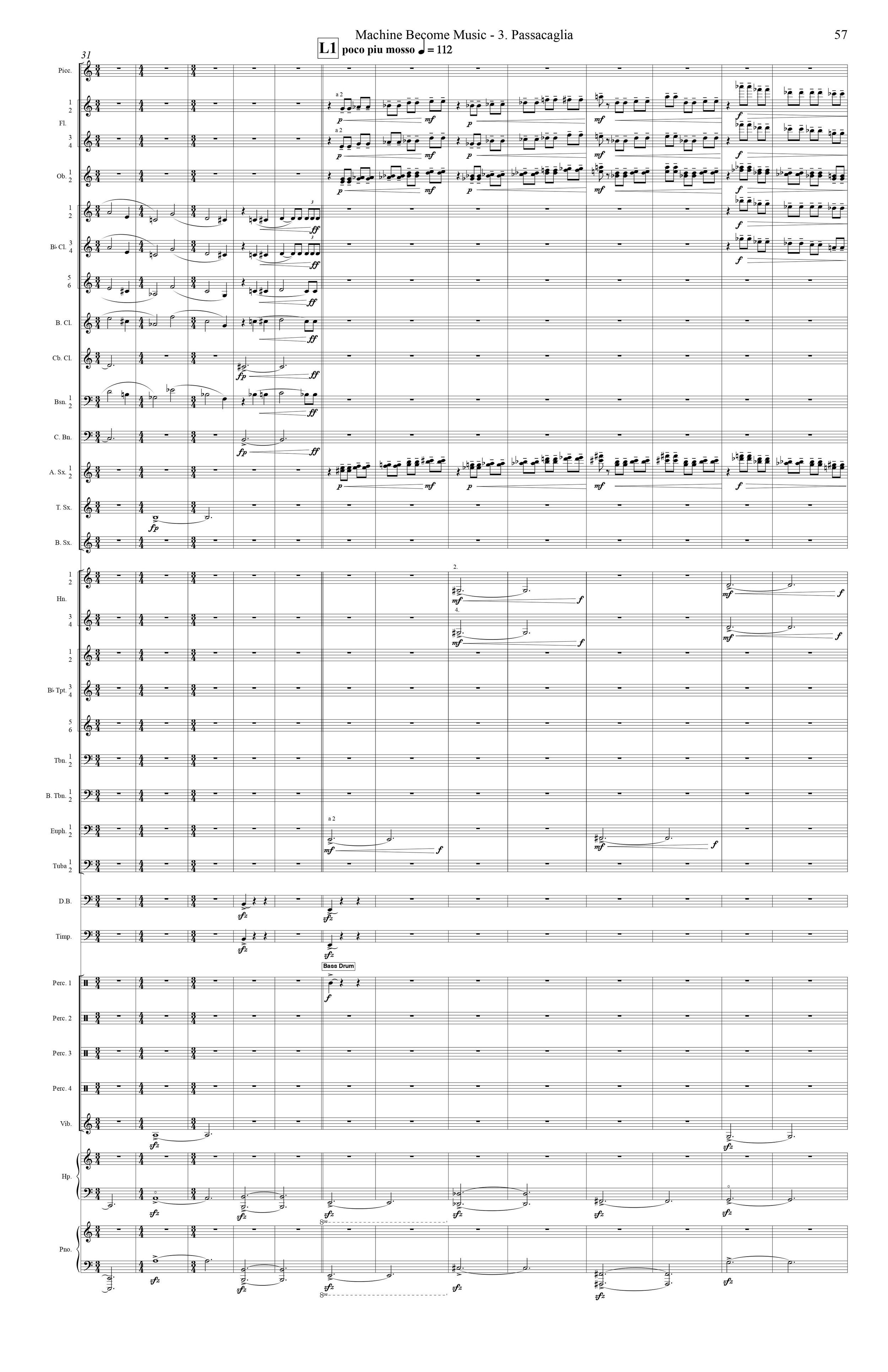

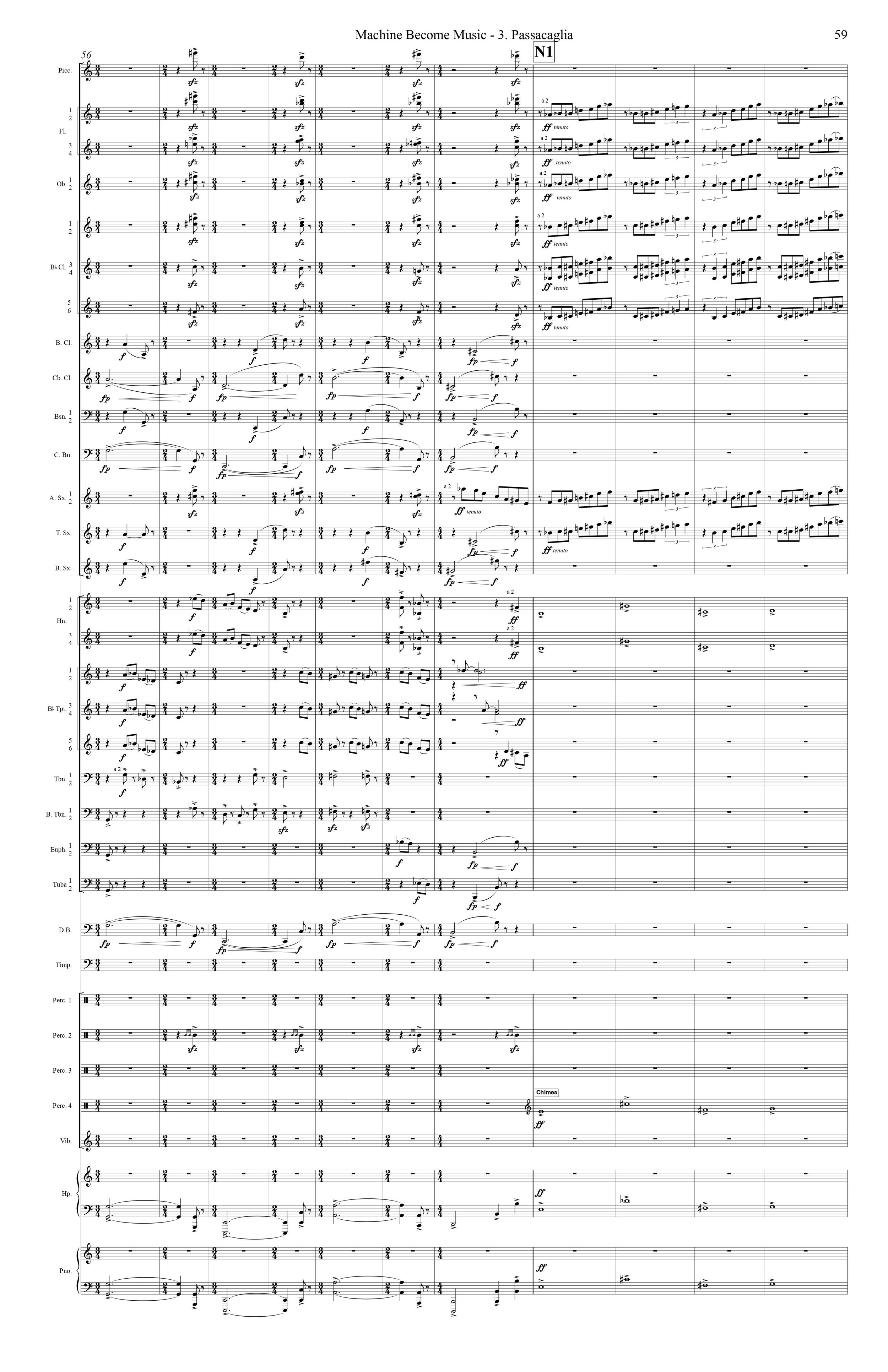

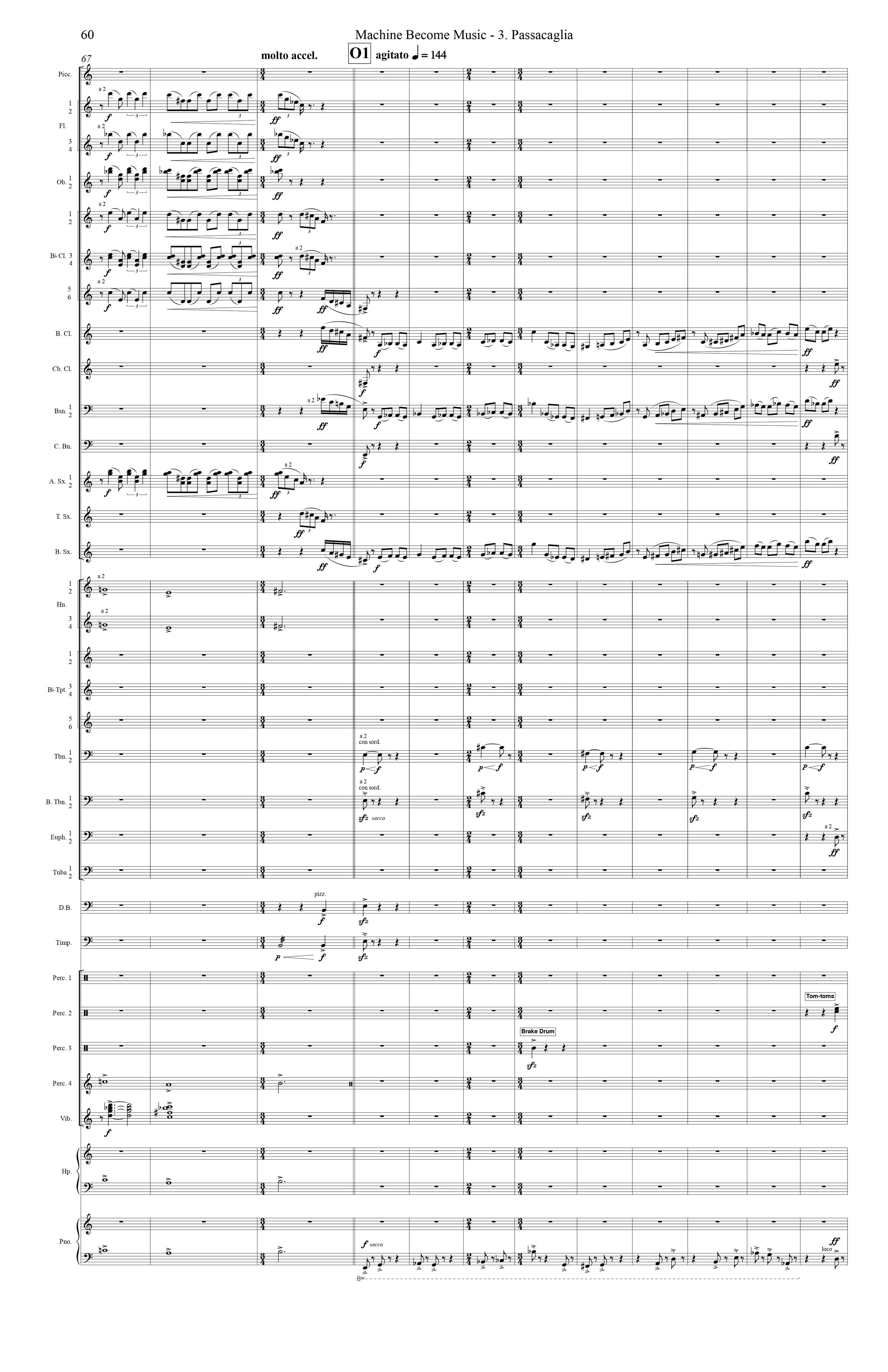

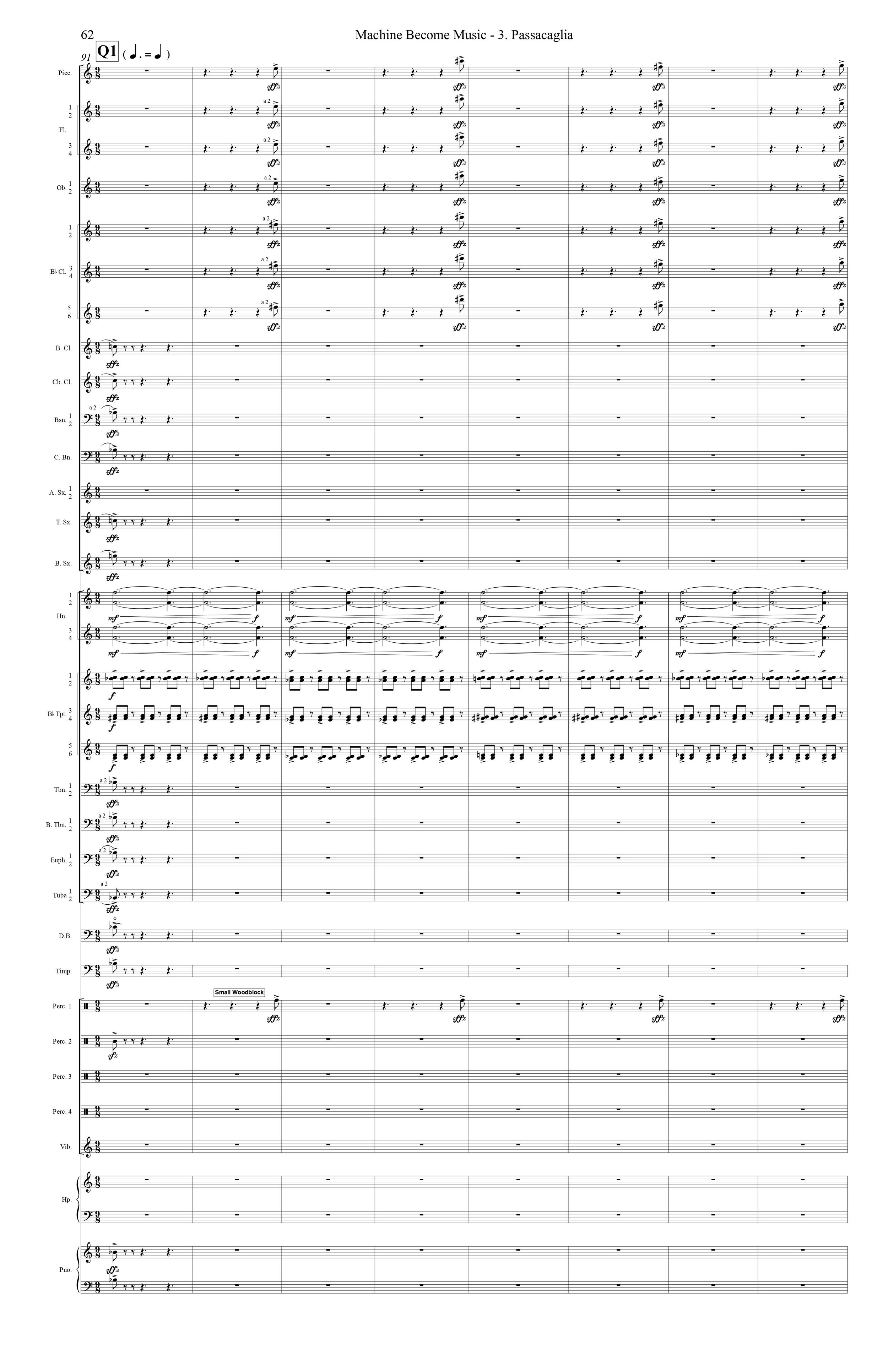

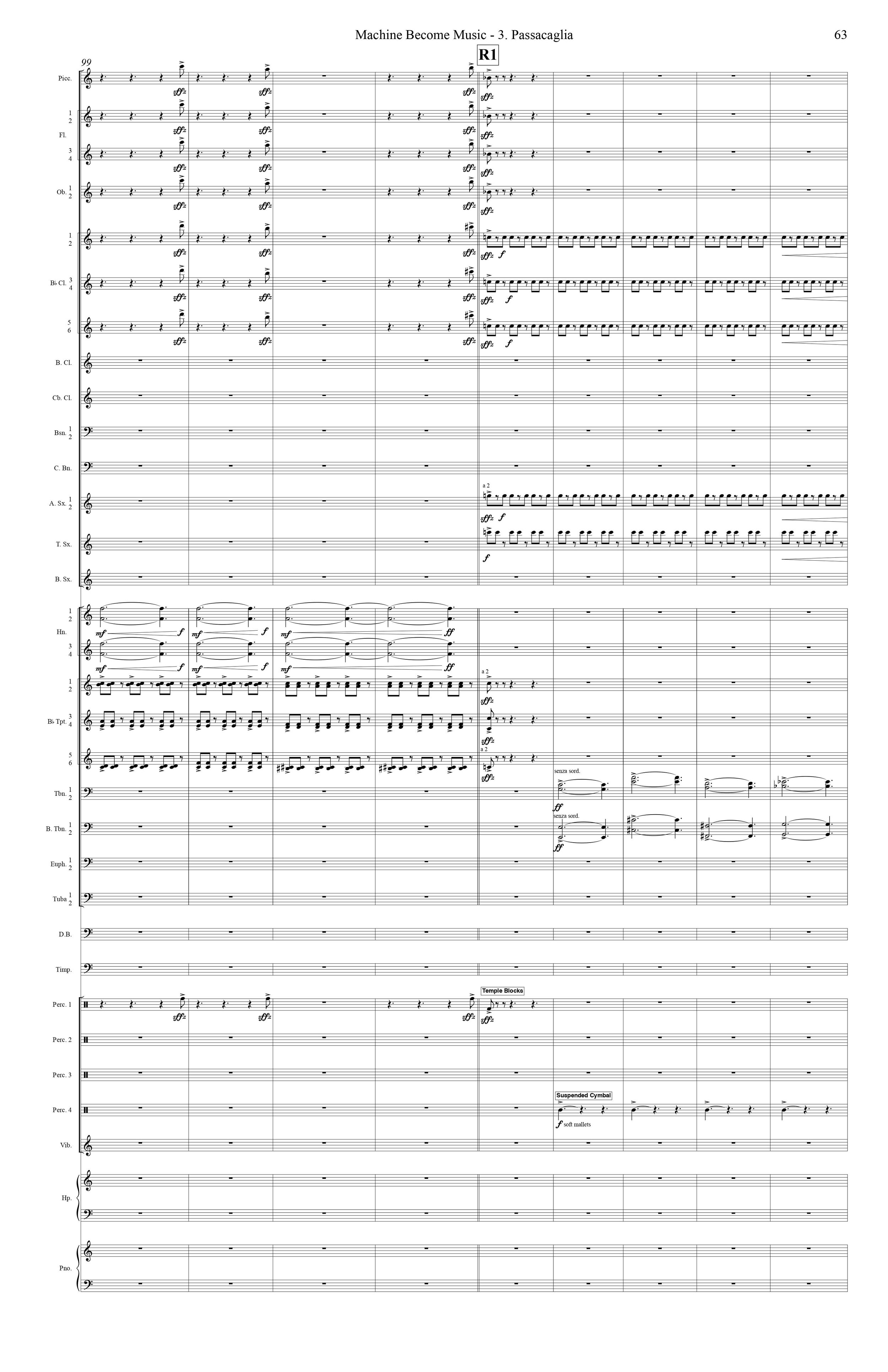

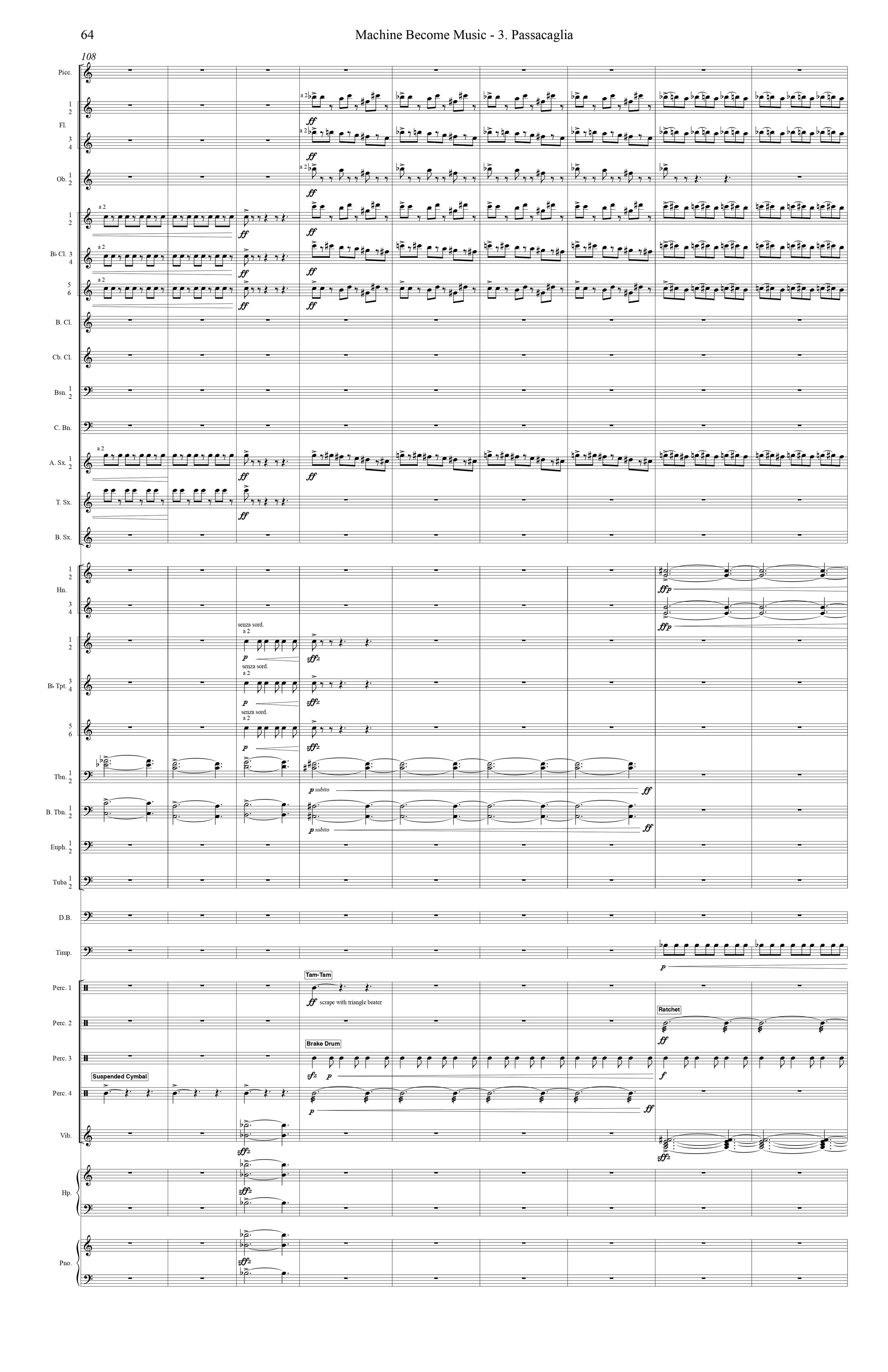

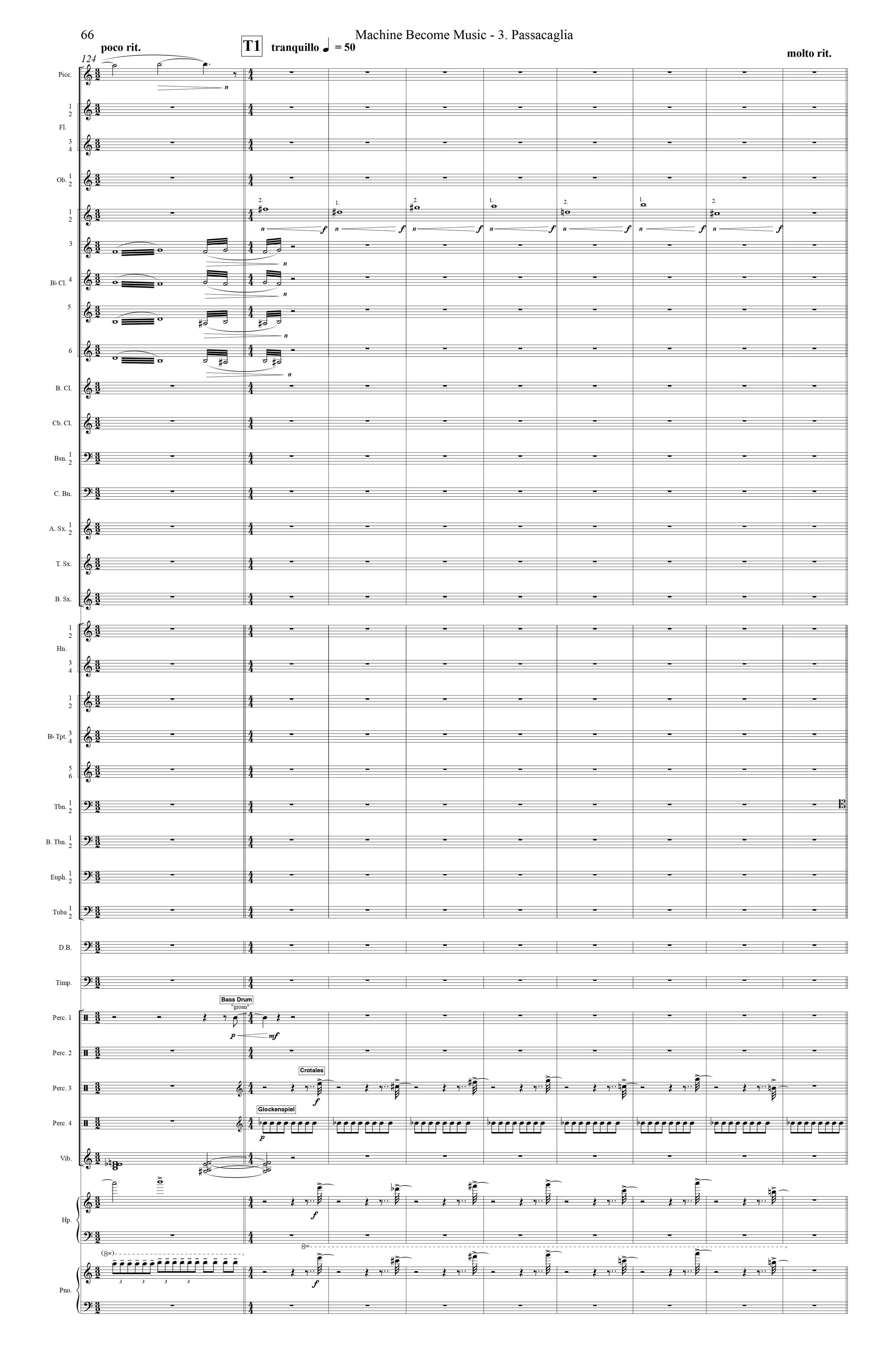

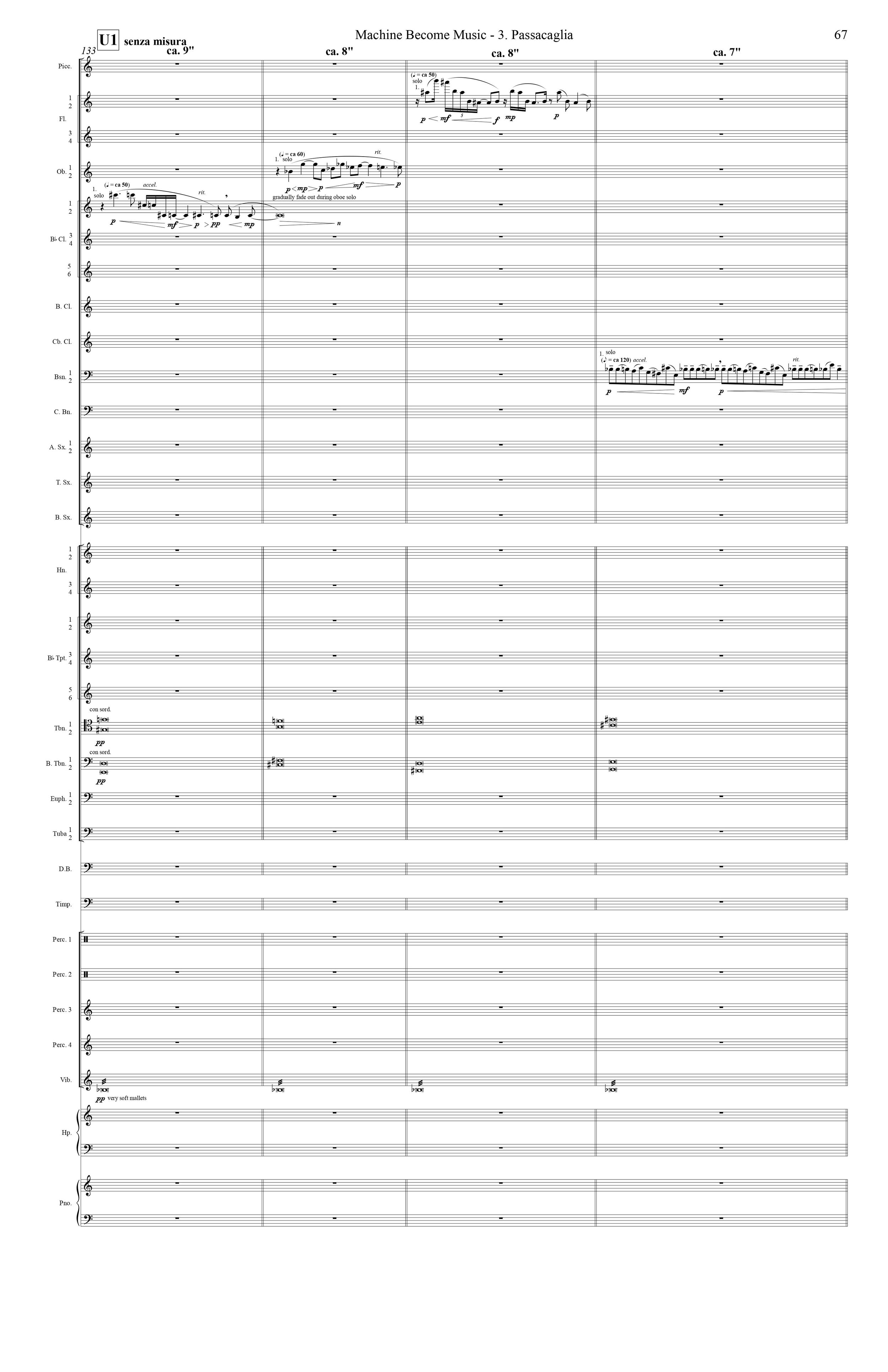

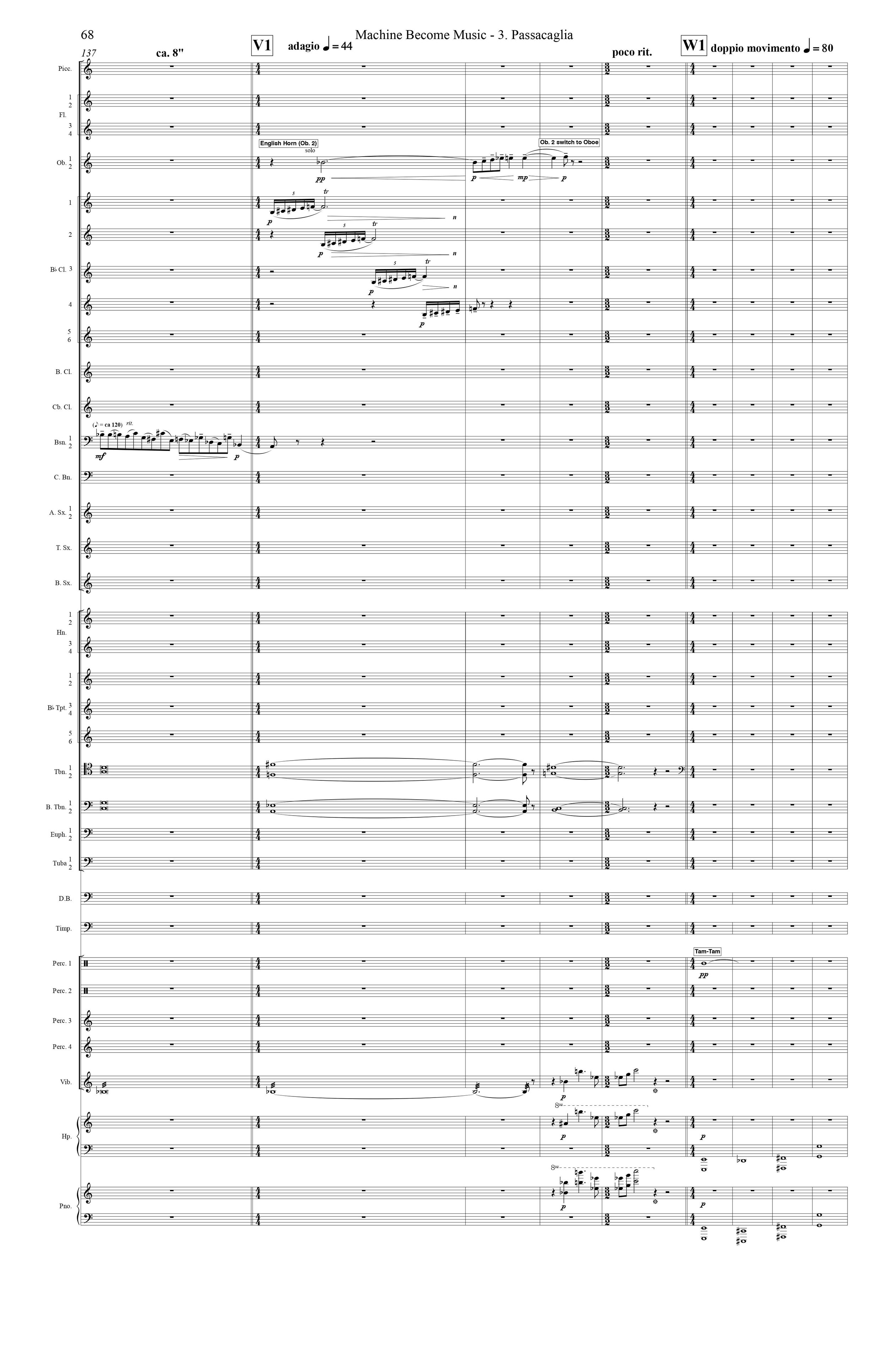

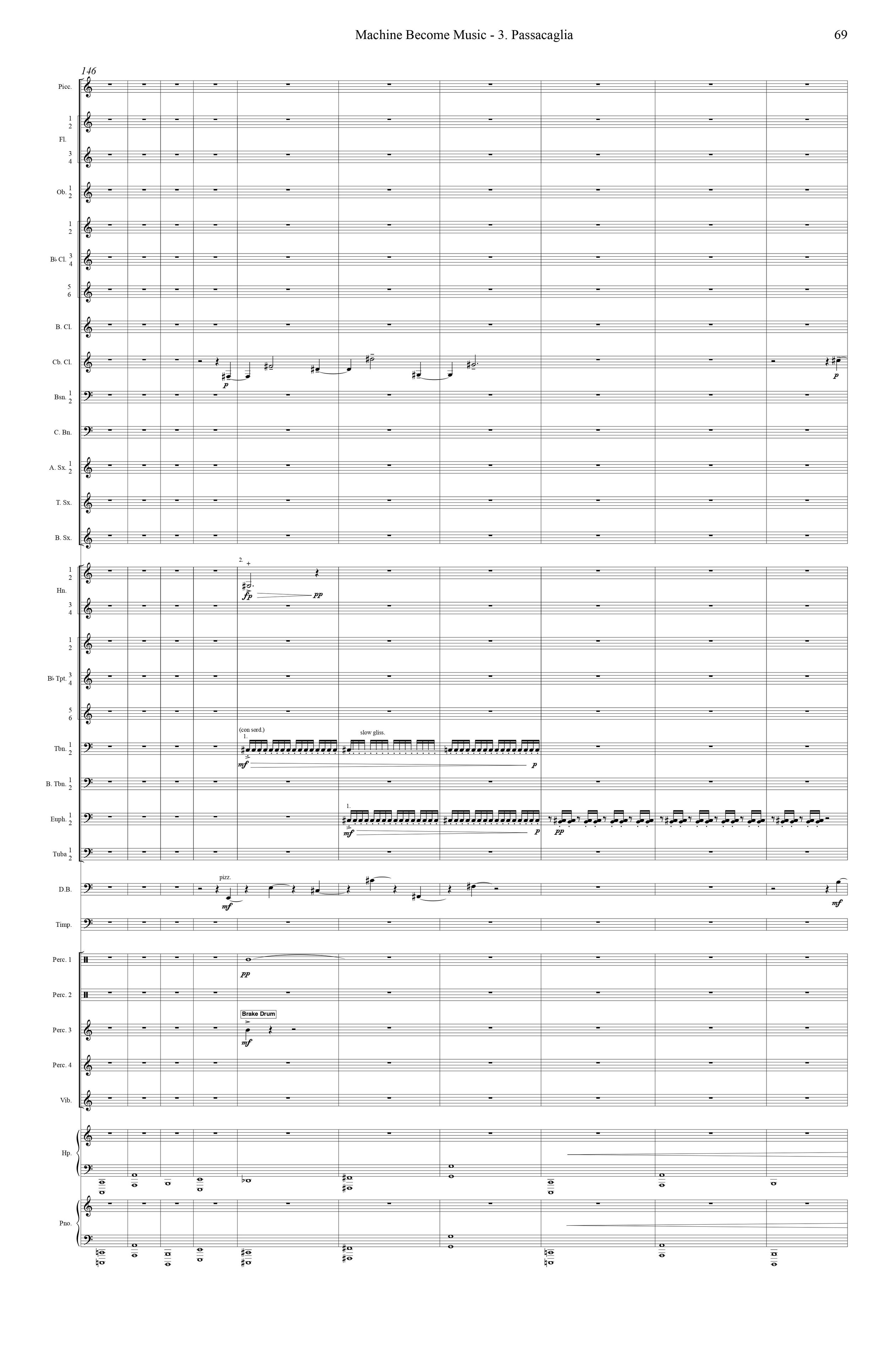

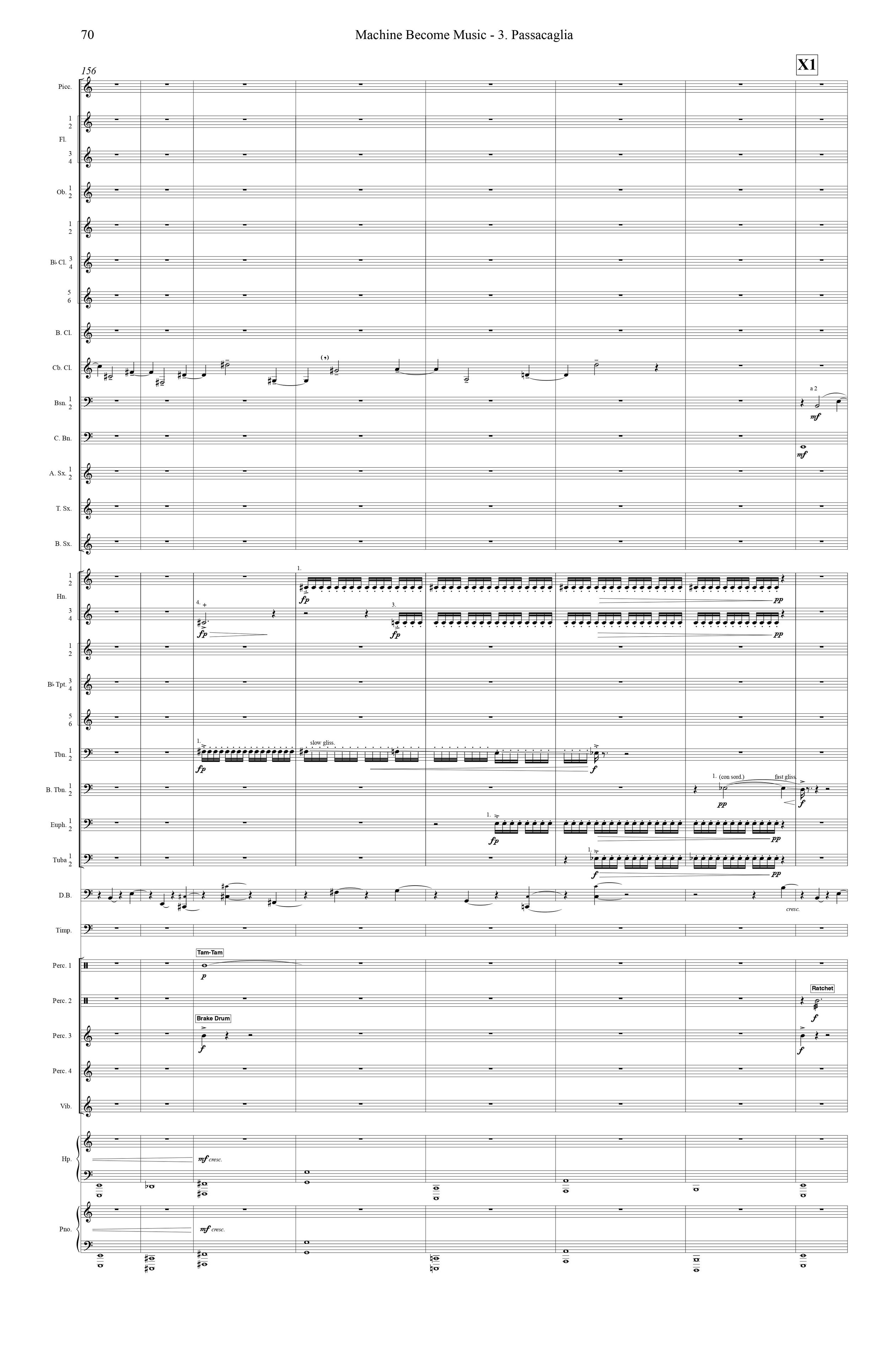

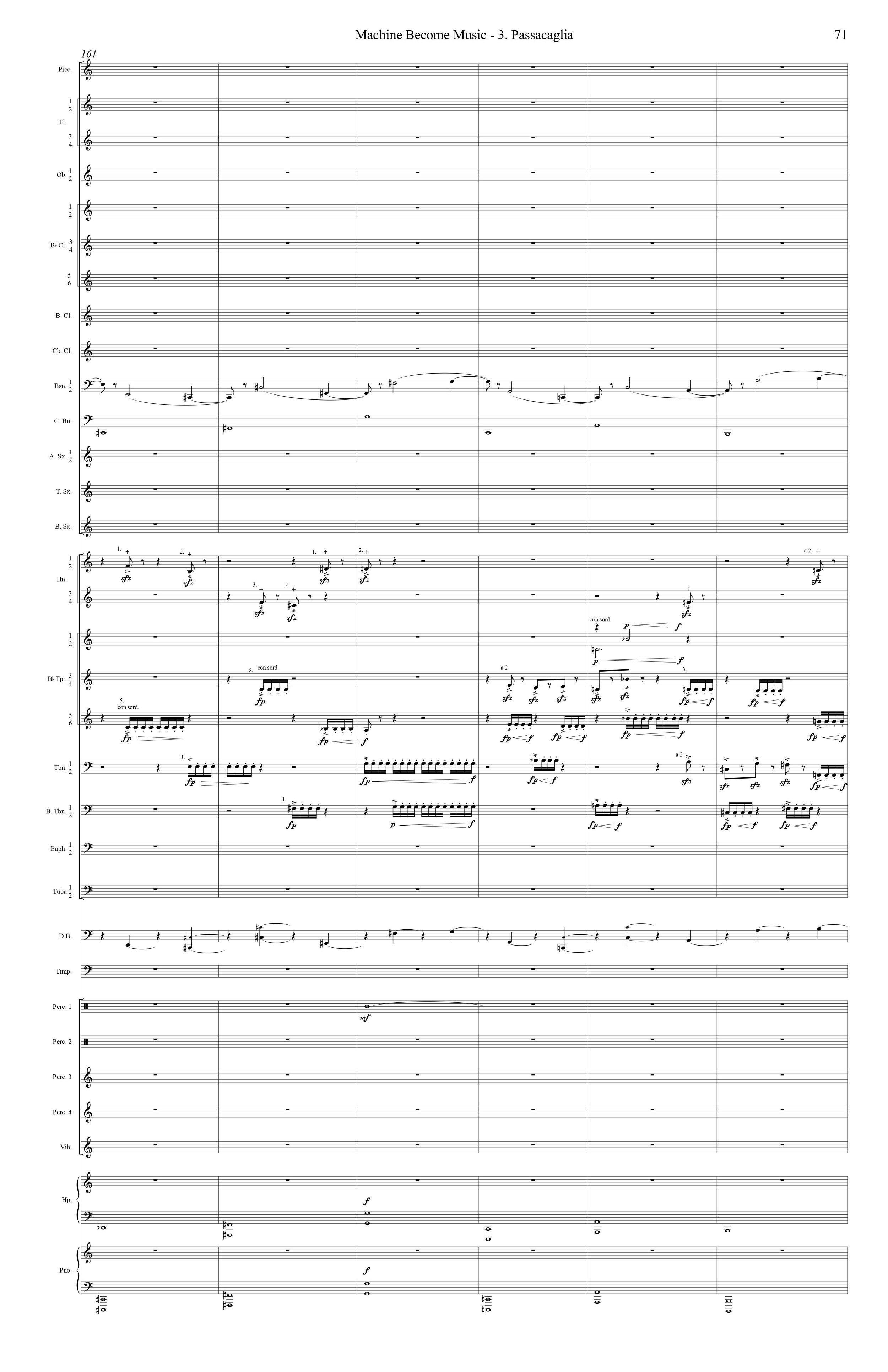

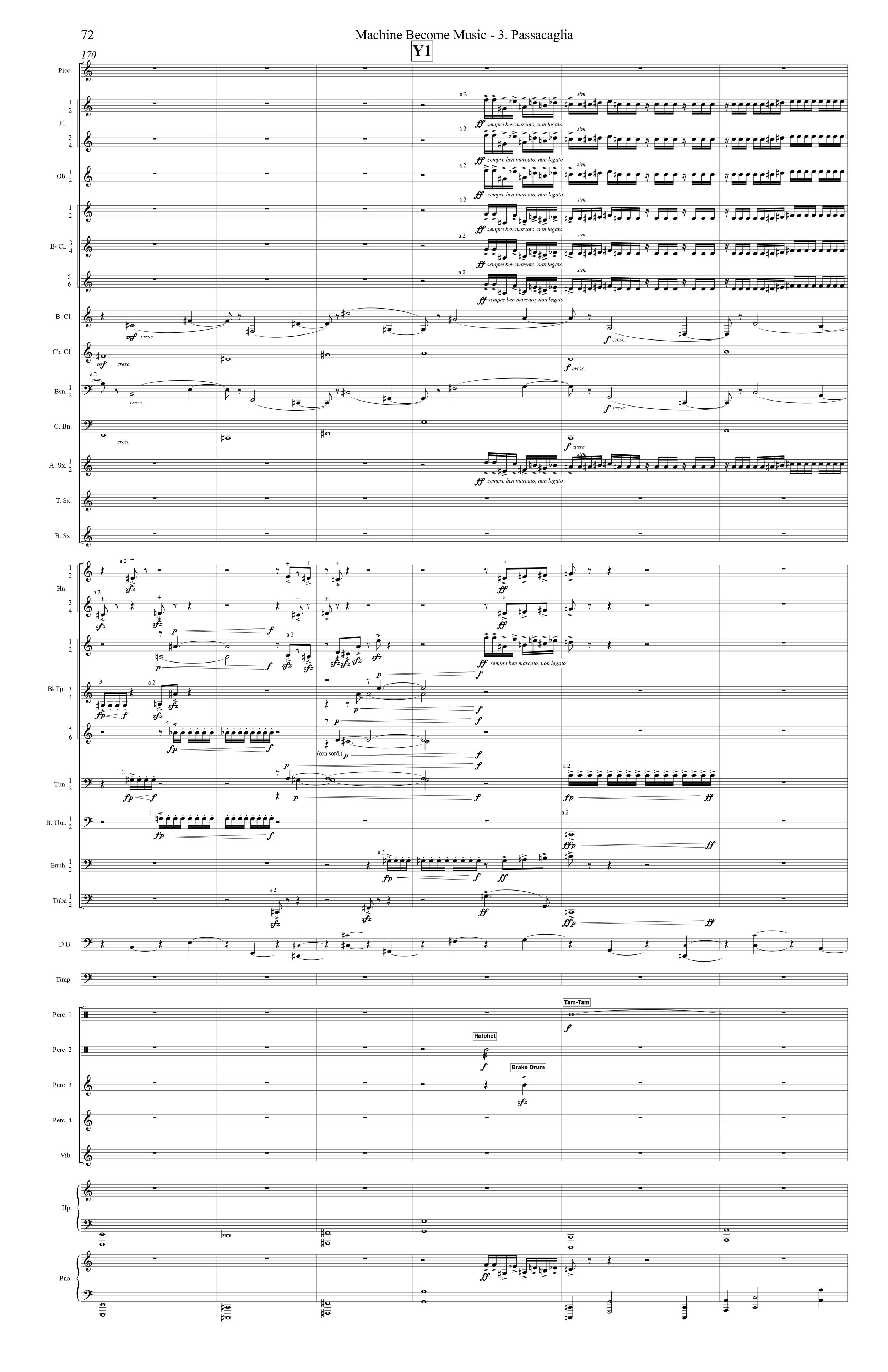

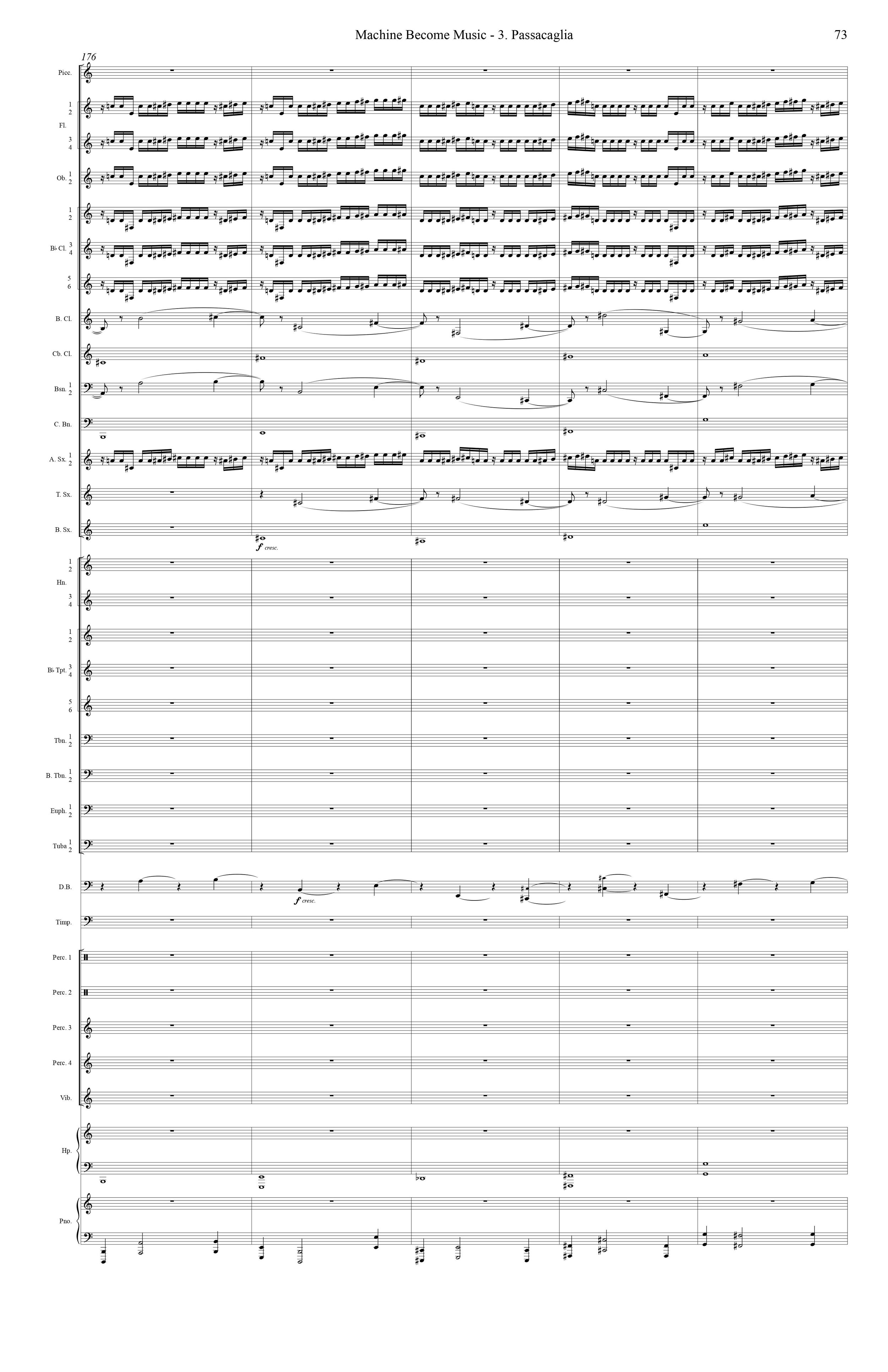

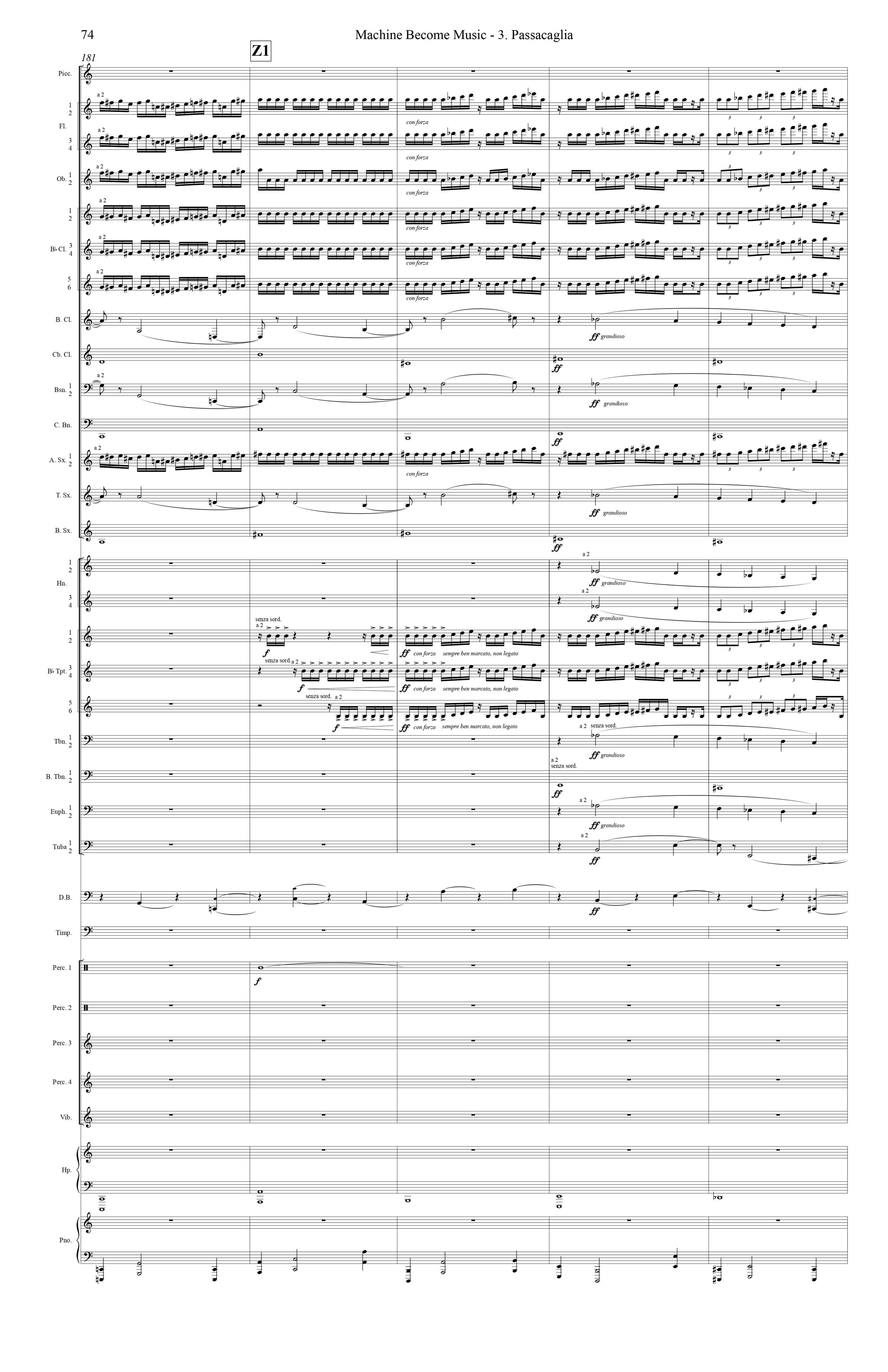

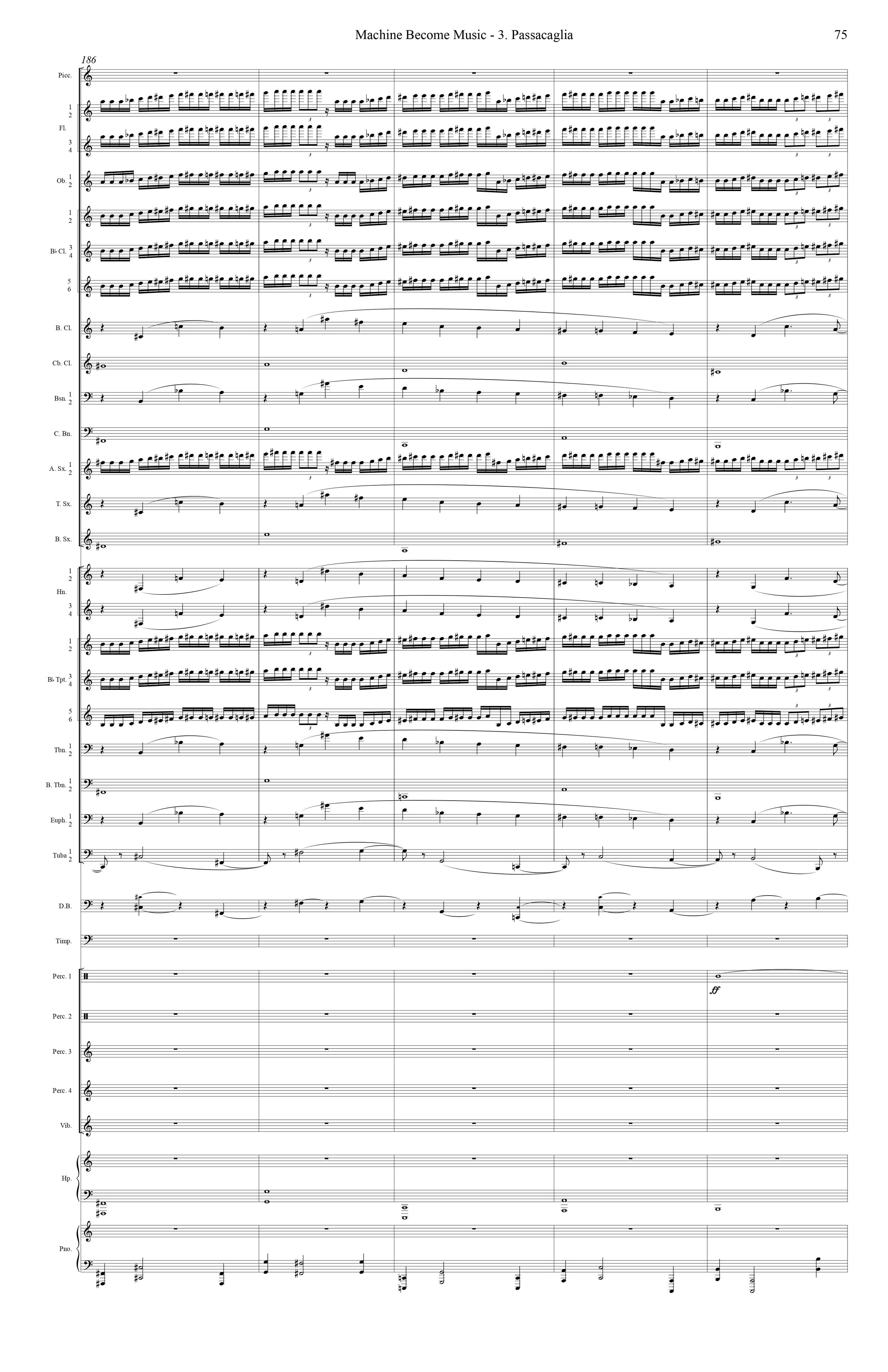

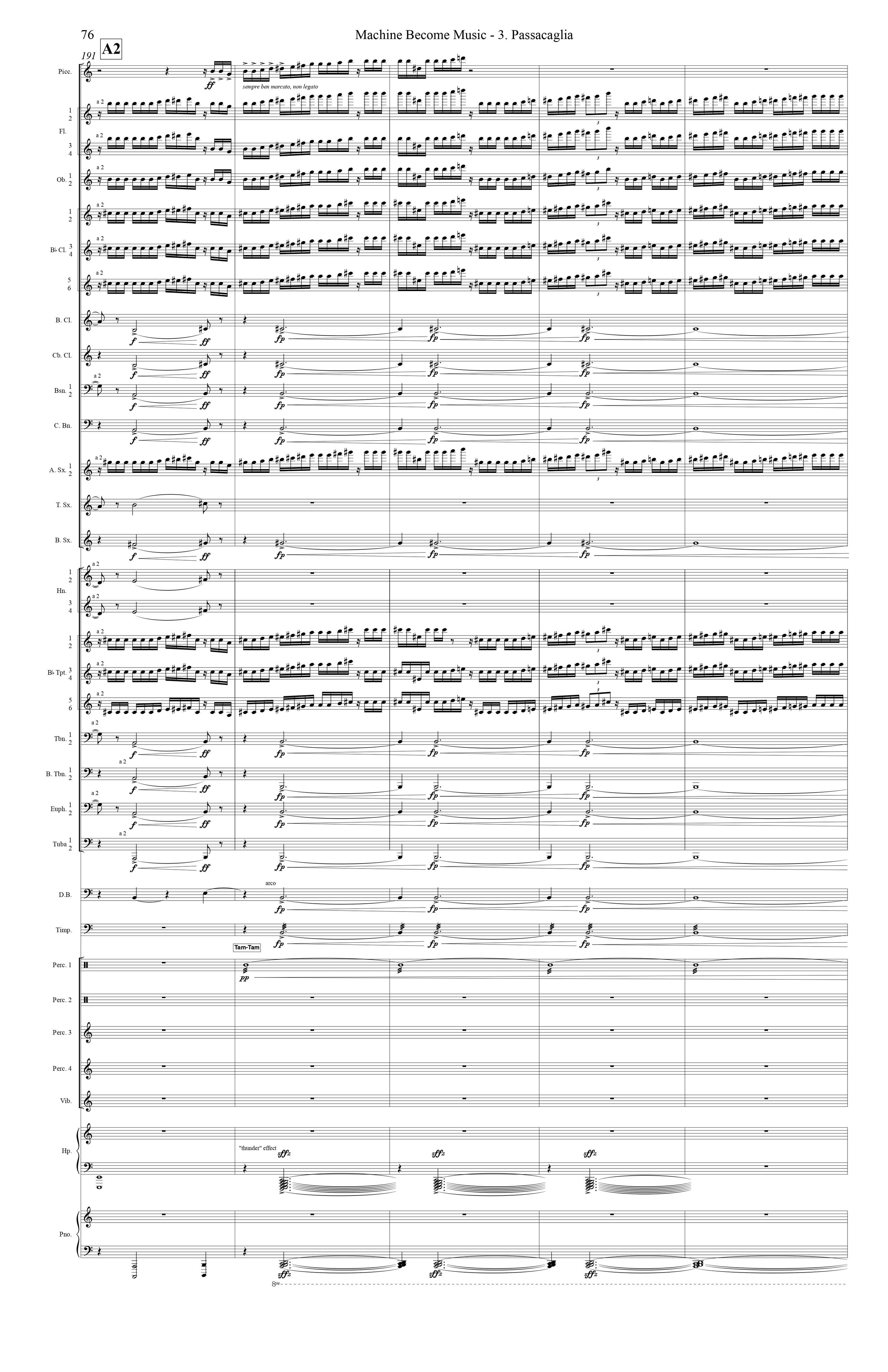

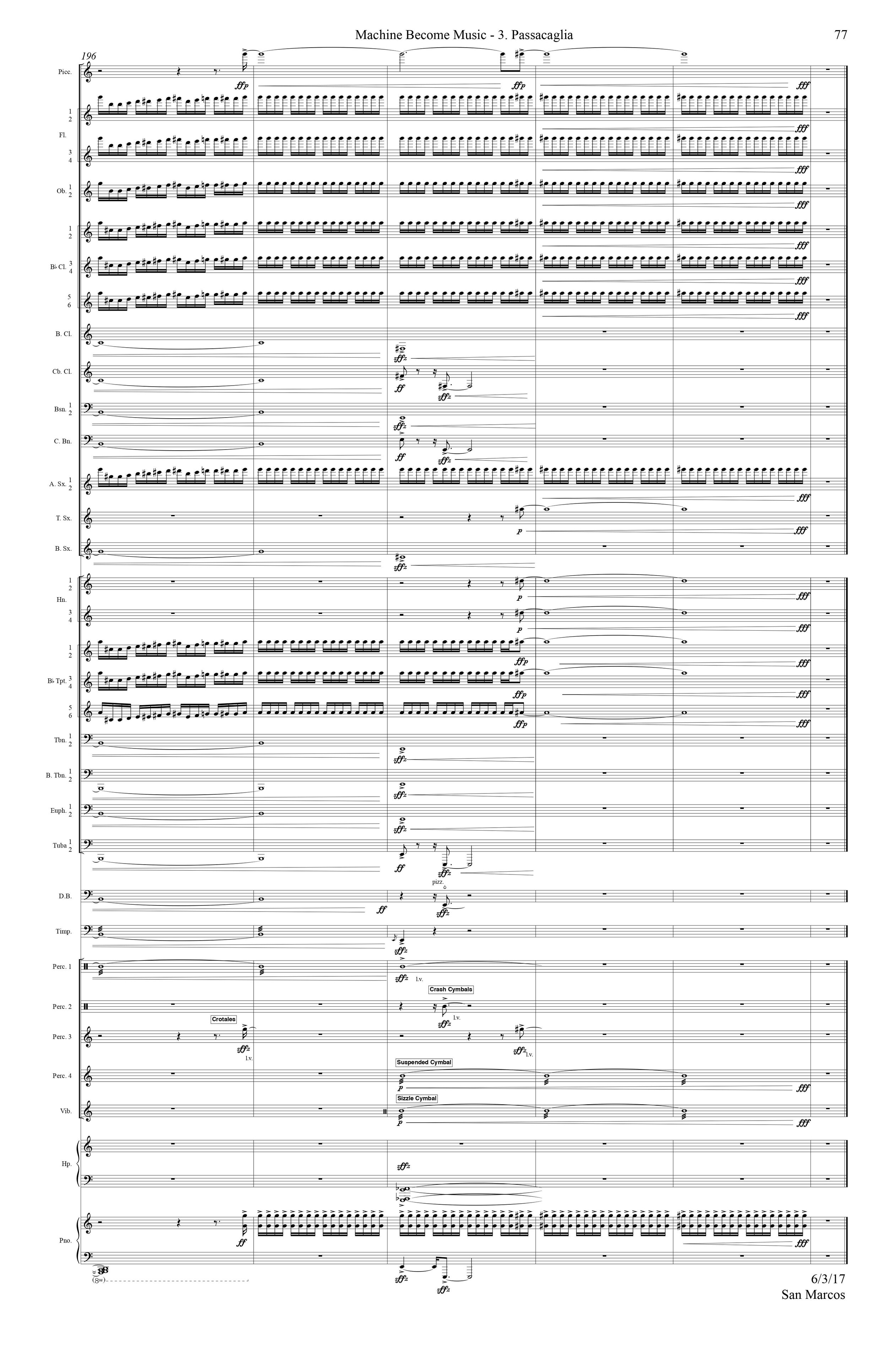

The last movement is a large passacaglia, a set of variations over an unchanging bass line. This bass line is first introduced alone, in long tones, and throughout the first section it becomes more and more compressed as other musical ideas pile up on top of it. A brief slow section follows, in which the bass line is more subtly hidden in the texture, and features solos for various instruments. The final section treats the bass line as a sort of inexorable march, gaining in power until the relentless hammering of the music finally crashes to a conclusion.